Status: In theaters (opened 8/21/09)

Directed By: Quentin Tarantino

Written By: Quentin Tarantino

Cinematographer: Robert Richardson

Starring: Brad Pitt, Christoph Waltz, Mélanie Laurent, Diane Kruger, Daniel Brühl

I often wonder what it would’ve been like to have lived through the careers of some of the great filmmakers of the past, watching them develop as they went along, refining and honing their craft with each successive film. How great would it have been to see, say, North by Northwest on opening night? Today we are lucky to have a few visionary writer-directors who are making their mark on the history of film in their own right—PTA, the Coens, Lynch, Lee—as well as a few still-working old-timers who serve as a bridge between modern times and previous eras of film—Lumet, Scorsese, Allen. I firmly believe, though, that the single most defining voice of modern-day American film is that of Quentin Tarantino, and getting to watch him develop as a filmmaker is one of the greatest cinematic pleasures to be found thus far in the 21st century. His newest film, Inglourious Basterds, demonstrates his maturation in several regards, most notably as a more-refined version of several of the stylistic devices he began exploring with the Kill Bill films. The word “masterpiece” doesn’t quite apply here, but only because it might imply that his previous works are somehow not as accomplished. They are the lot of them all masterpieces to one extent or another, but his newest offering comes as Tarantino’s most concentrated effort, simultaneously pushing new boundaries while re-addressing familiar territory with the confidence of an artist who has a focused, ambitious vision—and the wherewithal to execute on it.

Inglourious Basterds is told as a fugue in five parts. The first four of the demarcated chapters each introduce a particular voice along with its counter-melody, so to speak, and the fifth sees them all come together, twisting upon each other until everything comes to a head. There’s even a coda to wrap it all up with an echo of an earlier sub-theme. It’s a remarkable storytelling structure, not just for its complexity and the ease with which Tarantino keeps all of the characters’ interests present, but also for the tact with which he interweaves them together until they all spiral around each other, becoming entangled and overlapping and feeding back on themselves, leading to what is destined to be counted as one of the most absolutely satisfying climaxes there’s ever been in a film.

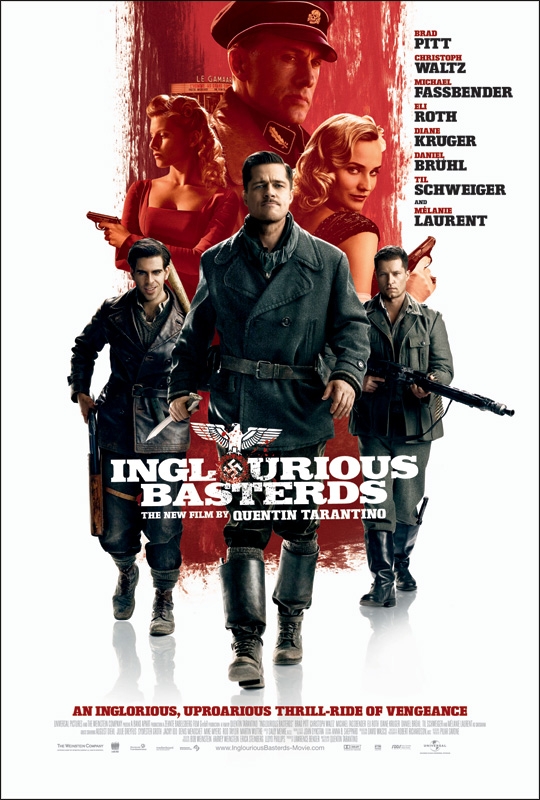

Brad Pitt gets top billing because he’s Brad Pitt, but he’s really only one of several primary voices in an ensemble—and global—cast. In Chapter 1, we meet Colonel Hans Landa of the SS (Christoph Waltz)—”The Jew Hunter”—who has been charged with rounding up any remaining Jews in Nazi-occupied France. His counterpoint is Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent), a Jew who escapes to Paris. In Chapter 2, we meet the “Basterds,” a group of Jewish-American soldiers assembled by Lieutenant Aldo Raine (Pitt) who mercilessly hunt down, murder, and scalp German soldiers. In Chapter 3 we learn that, three years later, Shosanna is now posing as the owner-operator of a Parisian cinema. She catches the eye of a German war hero named Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl), who is the subject and star of the newest propaganda film produced by Joseph Goebbels (Sylvester Groth). In Chapter 4 we become privy to an Allied plot involving a turncoat German actress named Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger). And in Chapter 5, all of these threads come together, as the interests of each of these characters intersect.

Tarantino weaves these stories around each other, and when it’s all said and done, they’re each resolved one way or another at the film’s climactic conclusion. Up to that point, tension is built on many levels, leading to a release unlike any other. Tension is definitely the name of the game here. Tarantino has re-teamed with his Kill Bill cinematographer Robert Richardson, and that collaboration has again resulted in a creatively- and beautifully-shot film. The familiar Tarantino technique of the camera encircling a table takes on a new meaning here, with faster revolutions increasing the tension of an interrogation scene, or slower movements achieving the same effect in a claustrophobic barroom standoff. Scene after scene is a textbook example of how to create suspense, with the fugue-style construction applying also to the pattern of tensions and releases, each segment developing and resolving its own minor conflict while also contributing to the overarching buildup of the primary plot thread.

Like Kill Bill, Inglourious Basterds is primarily a revenge tale. If there’s a main story to speak of, its heroine is Shosanna, and its antagonist is Col. Landa. In a cast that has few performances that are anything less than great, Mélanie Laurent and Christoph Waltz especially stand out, the latter in particular giving a command performance that sees him speaking no fewer than four languages fluently—and menacingly. This isn’t to say that Brad Pitt isn’t good—he is; in fact, it’s one of his best performances, and probably his most amusing. The cast is rounded out by some fun surprises: horror director Eli Roth as “The Bear Jew” Donny Donowitz (father of the cocaine-purchasing producer from True Romance), Mike Myers in a nice non-comedic turn as an English General, and some uncredited voice work from familiar Tarantino alums Sam Jackson and Harvey Keitel. Tarantino gets away with stylistic flourishes like humorous (and superfluous) titles in the middle of scenes and unevenly-used narration precisely because he has the chutzpah to use such devices when they’re not expected, and to do so reservedly, using them as an enhancement to the presentation of his tale, rather than as a crutch to lean on in the telling of it.

The soundtrack is decidedly Tarantino, featuring an eclectic mix that’s at once anachronistic and yet appropriately fitting. The musical themes during the Basterds’ scenes are similar to those from Kill Bill, but most of the rest of the score is of the spaghetti-western variety—there’s even a fair helping of Ennio Morricone, the godfather of the style. Elsewhere there are punctuations of blaring rock music, highlighted by a Bowie song that manages to fit quite well, given the context in which it’s used (“putting out fire with gasoline,” indeed).

Quentin Tarantino is undeniably one of the most talented filmmakers working today, not to mention one of the most creative, original, and unique. Each of his films has been at once a celebration of the history of cinema (of which he has an encyclopedic knowledge), as well as a significant and noteworthy new contribution to that very history. After Pulp Fiction made him a household name 15 years ago, the questions being asked where, “Did he peak too soon?” and “Where will he go from here?” I don’t think anybody could’ve imagined at the time what the answers to those questions would end up being, and indeed we probably don’t know them fully still. He’s unquestionably an artistic genius, and one of the preeminent filmmakers working today. The final line of dialogue in Inglourious Basterds is, “This just might be my masterpiece.” It’s not spoken by Tarantino (he doesn’t appear as an actor in the film), but it might as well be. I’d be hard-pressed to disagree with him.

great review, baby! don’t think it will be his masterpiece though! there is still more to come…