As was the case on the eve of The Dark Knight‘s release, I once again find myself feeling like I’m missing something as I consider the imminent release of James Cameron’s Avatar. In this case, at least, I’m pretty sure I’m not alone, and the grand declarations of the film’s importance are mostly due to its marketing campaign, rather than premature fandom. Still, though, there’re some lofty claims being made about this movie and the effect it’ll have on the entire film industry, and I find myself dubious of most of them.

The two primary claims in particular—as I perceive them—are that Avatar:

- is somehow revolutionary in the world of film, and

- will make you really believe in 3D movie-making.

I sometimes think that #1 is referring to #2, but usually it’s stated as if there’s more to the “revolutionary” aspects of it than the 3D technology alone. One commercial that I keep seeing on TV proclaims, “Movies will never be the same.” And from the trailers I’ve seen, I’m just not getting what exactly that’s referring to. Here’s the final theatrical trailer:

Seeing that and the other trailers for Avatar has thus far inspired one big “meh” from me. I can see how it might look really cool to some people, in a Lord of the Rings, fantasy/sci-fi, ultra-nerd sort of way, but I don’t see much that makes me think it’s very “revolutionary.” The counterargument seems to be that I will understand when I see it in 3D, because the television commercials and theatrical trailers just don’t do it justice. I’m withholding judgment on that aspect (as well as all others, hopefully) until I see it… but I’m pretty skeptical about it. I have yet to be really blown away by any of the films I’ve seen in 3D recently, and in fact more often than not I’ve felt I would’ve enjoyed the film more had the distracting gimmick not been employed.

Another area in which this movie is supposedly mind-blowingly amazing is the special effects, and unless they’re using temporary effects for the marketing materials, I’m pretty sure I won’t be too impressed by those, either. I have a pretty straightforward personal rule about CGI: If I can tell it’s CGI, then it’s shit. The whole point of special effects is to make you believe that what you’re seeing is real, isn’t it? There’s no caveat to that: “It looks really good for computer graphics” means it doesn’t look good for reality.

Don’t get me wrong; I think some of those terrains, and the planet Pandora in general, and some of the ships and vehicles look pretty amazing—real, even. The Na’vi, however—the blue-green inhabitants of the fictional world in which Avatar takes place—don’t look any different from the silly video-game characters of Robert Zemeckis’s Beowulf, and the creatures they ride don’t look any better to me than the cartoonish bouncing beasts from Attack of the Clones. Particularly when the Na’vi move, or when they speak, I feel like I’m watching a cut scene from a new video game, not a cinematic film—especially not a “revolutionary” one. The defense of this is always along the lines of, “They’re not humans, so they don’t move like humans, that’s why it looks weird to you,” which of course is nothing but a cop-out.

The film’s plot, likewise, doesn’t look like anything we haven’t seen before. Not to go too far in judging the book by its cover, but from the voluminous marketing material to which I’ve been exposed, I’ve gotten the distinct impression that the story of Avatar isn’t much more than The Matrix meets Dances With Wolves. (Or, as South Park called it, Dances With Smurfs.) Other reports of confusion confirm that I’m not alone in this.

As usual, I’m trying to remain as objective as possible and reserve judgment until I’ve seen the film for myself—which I’m intending to do tomorrow, in Digital 3D, so as to get the full advertised effect. But I have a healthy amount of incredulity heading into it. James Cameron has made some truly iconic films in his career, and I’m willing to give him the benefit of the doubt until proven wrong (which Titanic, his last film—12 years ago—almost did). Reading his Playboy Interview, it’s hard not to catch at least a little bit of his excitement about this latest endeavor. I’d prefer to let history be the judge of its effect on the world of film, though… and that’ll have to start with its wide release tomorrow.

I don’t know if this is necessarily a dream most people share or not, but it certainly holds true for me personally that I would love nothing better than the opportunity to write my own movie and eventually see it produced. Tucker Max, the blogger-turned-author-turned-screenwriter behind I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell, had the opportunity to do just that, and as I mentioned in my review of the resultant film, he was good enough to share the experience step by step with the world via a production blog that offered a surprising amount of valuable insights into the independent filmmaking process.

I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell‘s theatrical run has been, by any standard, a failure. Due to Max’s abundant stream of cocksure updates about the decision-making process he went through in bringing the film to theaters, though, I think there’s a rare opportunity to examine exactly why it was such a flop, and maybe learn something about the state of the indie film market as well.

From the start, Max’s fundamental assumption was that he had an undeniably great product on his hands. This was not entirely blind self-confidence: the book that was used as the movie’s source material has sold over a million copies (according to Tucker Max—I couldn’t find definitive sales numbers anywhere), and it has appeared regularly on the New York Times best-seller list over the past 4 years (the current list credits it with a tenure of over two years). What he was incorrect about, however—among several other things—was in making the following additional assumptions:

- Everybody who considered him or herself a fan of his book would naturally seek out (and pay to see) his movie.

- These people would not only provide him with a built-in audience, they would also provide him with the necessary word-of-mouth advertising to turn the film into a widespread hit.

In his theatrical run wrap-up post from a few weeks ago, Tucker relates a story of an encounter with a self-identified fan who was completely oblivious to the movie’s existence. He correctly recognizes that the movie’s poor box office performance was due—at least in part—to “a complete failure in the publicity and marketing of the movie,” but true to form, he’s quick to imply (in not very indirect terms) that it is the fault of others:

Part of it was a lack of experience, part was naive optimism, and part was straight up malfeasance by certain parties involved with the movie.

This borderline tinfoil-hat assessment is in character for Max, but given his previous candor about the decision-making process (and his personal role in it), it’s hard to buy the conspiracy theory angle he’s trying to sell—though I’m sure it’ll be amusing to read his promised forthcoming explanation of that aspect of it. Even his claims of naiveté don’t totally fly, though, particularly if you examine his posts leading up to the movie’s release that revealed the self-education on independent film distribution he was (impressively) able to attain. Back in July, he wrote a primer on how film distribution works, and his tone in it is quite telling: confident that he had a hit on his hands, Max settled on a deal that was “an incredibly risky one, one that will pay off huge if the movie does well, and hurt us a lot if it fails. High risk, high reward.” I suppose you gotta admire the guy’s bravado, if nothing else.

Max’s description of their distribution model of choice goes on:

Normally, this is not an option available to an indie, because most indies don’t have any real commercial appeal, so no one wants to invest 35 or 20 or even 5 million dollars because they don’t think they’ll get their money back. But we are different–we have a broad commercial comedy that we could have sold to a studio at any point in the process, and based on the quality and reaction to the movie, Darko [the film’s production company] was able to independently raise the P&A we needed to distribute the movie ourselves.

[…]

On even a 40 million dollar box office with this movie, we are all swimming in money, whereas with a major distributor, we might have to hit 60 million before we start to see even pennies.

Even ignoring the lofty numbers he’s talking about, there’s a lot of confidence in his product behind those words, but I think it’s quite obviously unfounded. In that wrap-up post from a couple of weeks ago, Max had this to say:

I’ve seen every reaction, read every email, seen every review, and talked to more people about this movie than anyone else. No one has been more on the ground and seen more actual audience reaction than me. I know what real people who have actually seen the movie think about it, and it’s going to do great, given enough time.

He’s mostly referring to the month-long premiere tour he took the movie on; you can view videos from all of the stops at the movie’s YouTube channel. There’re a couple of interesting phenomena at work there, though, both of which I think contribute significantly to leading the filmmakers to believe that audiences like their movie a lot more than they actually do.

The first (and obvious) one is that people who go to the effort to purchase advance tickets, stand in line, and go to the general trouble of seeing the movie on a premiere tour stop are already predisposed to liking it. To even know about the movie in the first place, they’d probably have to be pre-existing fans of Tucker Max and his books. And to know about the premiere tour, they’d probably have to have been following his blog already. This all adds up to the fact that they’re likely going to be fans of the movie pretty much by default.

I think more interesting, though, is what I’d call the “I Was There” phenomenon. I used to encounter this a lot when I was in college and would go to see Phish a lot. People would often post show reviews on Usenet and mailing lists, and those that came from a guy who lived in the town where last night’s show took place—and who only attended that single show on the tour—never had much credibility. Invariably, said guy would gush about how great the show was, how it was the best of the tour, and how everybody should seek out tapes of it. There’s something about being “in” on something, experiencing it first-hand for yourself, especially when it’s something that’s not widely known about—it adds a counter-culture aspect of exclusivity to it, as well. I think this definitely occurred on the I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell premiere tour, and the audience reactions in the tour videos certainly seem to bear this out. (Of course, they’re also only putting positive reactions in the videos in the first place.)

If you’ve read my review of this movie, you know that at the most basic level, I think there’s a really easy explanation for why it was such a flop: it’s not good… at all. Even the trailer isn’t funny: there’s nothing in there that I can imagine would make the average filmgoer think, “Man, I wanna see that!” But I do harbor some respect for the process, for the way they attempted to go about doing things. Max sums it up fairly succinctly:

If you care about independent film or helping artists own their work or just generally root for the underdog, you are looking at that philosophy embodied in reality, right in front of you. We are not sitting around talking aimlessly about how we wish we could beat the system; we are putting our money and reputations on the line and trying to do it.

That, in a nutshell, is why I’ve paid so much attention to this movie from the get-go, and why I’ve been so interested in seeing how it does. Conversely, though, since I think the actual content was so poor, it’s hard to come to any hard conclusions based on this one example.

The biggest irony in all of this is the headstrong, self-confident series of assumptions behind the decisions that were made, most readily characterized by a post made back in June. There Tucker says, “For over five years I have looked at this movie as the first major battle in the grand campaign to change the entertainment business.” He takes his cockiness to the point of absurdity, albeit with an admirable slant:

We examined the “normal” Hollywood way of making a movie, found it to be stifling to creativity and utterly evil in how it treats artists, and consciously rejected it. Instead, we took another path:

We wrote a different way–not worrying about what would sell or what we were “supposed” to do, instead focusing on nothing other than what made the best movie.

We financed it the right way–turning down upfront money and guaranteed “success” so we could do the movie with a company who would respect our artistic vision and give us creative control.

We made it the right way–by hiring people who got our vision and wanted to do it the right way, not the “Hollywood” way.

And we are marketing it the right way–by engaging fans in the process, being completely honest with them, and always treating them the way we would want to be treated, instead of shilling and lying to them at every turn.

The ideas expressed there are great, in a pie-in-the-sky, naively dream-like kind of way. If you can choke back the snickers every time he refers to himself as an “artist,” in fact, that post in particular is well worth reading in its entirety. The ironic part is that there is nothing ground-breaking about the movie that came out of this process (no matter how many claims to the contrary are made by its originator). The writing was trite and unoriginal, the production half-assed, and the marketing—premiere tour aside—uninspired.

If it sounds like I’m sort of vacillating between the two extremes of hating and loving the endeavor that is I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell, the movie, it’s because that’s where I stand: On the one hand, it’s a bold attempt at doing something different, if not in its actual content then at least in its approach. On the other hand, it’s a shitty movie. That makes it hard to judge the totally independent, outside-the-norm process on its own merits. Max sums up the situation like so:

For maybe the first time in history, the creator is free to be who they want to be, to create what they want to create, and to not have to answer to the interests or demands of the powerful, or of anyone but themselves.

It’d be great if that were true—and I think that in some ways, it probably is—but unfortunately the manner in which Tucker Max chose to exploit such a level of creative freedom was quite underwhelming. He’s absolutely right, I think, that “audiences are craving originality and meaning”—he’s just not providing either of those things.

There’ll be more and more films that attempt an approach like this, and I’m sure some of them will be successes in one way or another. While I care a whole lot more about artistic value than box office returns, the latter is always nice to see, too, especially since it serves to give those artists further chances at realizing their creative visions. An indie doesn’t have to go to Paranormal Activity heights to be considered successful, either; oftentimes doubling its (presumably meager) production budget can be considered a huge success for a small-budget film that finds a strong following and capitalizes on it. Given the chance to predict Beer in Hell‘s box office take, I probably would’ve put it right around that level—about $15 million. That it struggled to scrape one-tenth of that total, I hope, doesn’t mean the movie-going public won’t embrace this approach to production or style of distribution when other, better films give it a shot in the future.

Comments Off on Hubris, Greed, and Failure

Since I live on the west coast, I only rarely get to watch baseball games live. My team, the Chicago Cubs, plays most of their games at either 1:20pm or 7:05pm Central, and I’m rarely home from work in time to catch the beginning of even the later-starting games. I don’t really mind this, because watching on DVR delay means I can skip through commercials, and I’m typically busy enough at work that not spoiling the score (or outcome, in the case of earlier games) isn’t too difficult (although sometimes, when the sky is clear, I’ll listen to a day game on XM while at work, but that’s a different situation). The ideal goal is to have just the right amount of buffer built up so that you catch up to real time in the bottom of the ninth inning, having missed all of the commercials but seeing the game end live. I’m almost always a bit off from that, though, as I don’t usually begin watching a game until a couple of hours after it’s started.

Because of my viewing schedule, and my desire to remain ignorant of anything that’s happening with a particular game I’m going to watch until I’ve seen it for myself, I have my DirecTV +HD DVR set to record every Cubs game from the time it starts until 3 hours after it’s scheduled to end (that’s the max amount of additional recording time for a particular program that the software offers). This gives an allowance for rain delays and/or extra-innings games. Since I watch games every day, the wasted disk space on the DVR isn’t much of a problem—I just delete each game after I’ve finished watching it (which is usually while it’s still recording, due to the extra 3-hour record time).

This sounds like it’d be a good situation for someone like me, and it is, for the most part. The problem with it, though, is that it relies on heavy use of the DirecTV DVR software, which I have now decided is definitely the single worst piece of software I’ve ever had to use on a regular basis. Last year it made me miss Zambrano’s no-hitter, and while there hasn’t been anything quite that dire yet this year, it has nonetheless found other ways to annoy the ever-loving shit out of me on a way-too-frequent basis.

The most recent example involves the way DirecTV tries to be way too clever with their guide: despite the fact that they dedicate an entire channel—two, actually, for games that are available in both standard-definition and HD—to a game for a whole day, for some reason when the game actually ends they update their guide information so that the receiver/DVR knows the game is over. This results in the guide deciding that the channel is now devoted to a different, upcoming game, which, despite the fact that I have the MLB Extra Innings package and would be able to watch when it’s actually on, I am not yet authorized to receive. The result of this is that when I’m tuned to that channel—or in my case, watching DVR-delayed content from earlier on that channel—the DirecTV DVR decides that I am not authorized to watch it, and finds it necessary to repeatedly inform me of this… while I’m still watching the game.

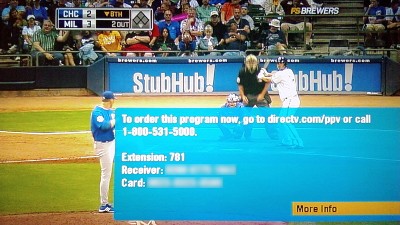

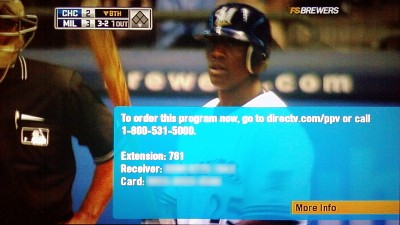

This is what last Friday night’s Cubs-Brewers game looked like for me during the final few innings (click to enlarge)

So I get this annoying box popping up, occupying over a quarter of the screen, at random intervals and for seemingly-random lengths of time… and it doesn’t respond to my remote’s “exit” button. I can select the “More Info” box, but all that does is obscure the screen even more, until I hit “exit,” at which point the info box disappears for a few seconds before popping up again. This happens from a point shortly after the game ends (I think it’s a half hour) until I’m done watching it.

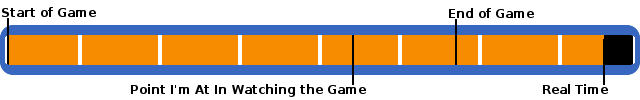

An illustrative timeline might clarify, if my description has been confusing at all:

What’s really odd is that this doesn’t always happen. From my casual observations, it seems to only come up when I’m more than a certain amount of time behind real time. For example, call the difference in time between when the game starts and when I begin watching it “interval A,” and the difference in time between when it ends and when the guide data changes “interval B.” I think that if interval A is greater than interval B, then at “interval B” time after the end of the game, the “To order this program now…” box will begin displaying on the screen. (The corresponding guide data change would be, in this instance, from “Cubs @ Brewers [HD]” to “Upcoming: Cardinals at Reds.”)

The one solution I’ve found is as follows: once the box starts being displayed, I have to stop watching the game and change the channel to something normal (i.e., not part of a sports package). I then have to stop the recording, and then resume watching the recorded game. I’m always a little nervous to do this, though, because I’m not positive that my theory of what causes this to happen is correct, and I don’t want to stop the recording only to find that I’ve caused myself to miss the end of the game. And it doesn’t always do the trick, anyway. At any rate, it’s really not something I should have to contend with in the first place, and the fact that it’s just the result of sloppy programming on DirecTV’s part only makes it that much more annoying when I do.

A sentiment I seem to encounter often is that it is wrong for college sports to be such a big-money business, and that tying the high expenditures of running nationally prominent programs and the corresponding high ticket prices to the pursuit of higher education is a practice that should be tempered, downplayed, or disbanded altogether. This thought process universally comes from those who are not sports fans themselves, but more importantly, it typically comes from a position of ignorance for how the world of collegiate athletics actually functions. I don’t claim to be an expert on the matter by any means, but I have noticed a significant amount of evidence that contradicts the basis for nearly all of these arguments.

“This is what my tuition money goes towards?” While that might be a funny comment to make, especially as a means of downplaying a particularly embarrassing loss by your school’s team, it’s not based in any sort of truth. I heard this often at the University of Illinois, whose school paper recently ran an article that explicitly disputes it: “We take no university funds,” assistant athletics director Kent Brown was quoted as saying. This is, as I understand it, typically the case at major university athletic departments: they are self-sustaining (and then some), through booster contributions, ticket sales, and media contracts.

The funniest recent example of this type of dispute coming to a head was when a “reporter” last month asked Connecticut men’s basketball coach Jim Calhoun if he might be morally obligated to return a portion of his nearly $2 million salary to the school, as the state’s highest-paid employee during a time of economic crisis. Calhoun responded in the manner of making the strongest argument possible: with facts.

He points out what should be obvious, that in the true fashion of capitalism, college athletics are big business because they are profitable. The sports teams are in a mutually beneficial relationship with their institutions: they promote their university’s image nationally, while bringing in high dollar amounts for the school in the process ($12 million a year, according to Calhoun, in the case of Connecticut’s men’s basketball program—and their women’s team, as one of the top women’s basketball programs in the country, presumably does nearly or equally as well). In exchange, by being tied to universities, the sports programs get a semblance of credibility (and innocence) that they would not have were they not affiliated with educational institutions. There’s also the fact that they often attract a lot of student-athletes who would not have otherwise attended college at all, in some cases (as with Bob Knight’s track record, for example) maintaining graduation as the ultimate goal. The argument here is often that these athletes are less deserving of receiving the educations they are given for free, which might have some validity, though it’s hard for those adopting this position to phrase it in a way that doesn’t smell of racial undertones.

What I mostly take issue with, at any rate, is how this discussion is often framed as being a matter of those who are concerned with the “purity” of higher education decrying the institution’s sullying at the hands of those silly sports. As if a student-athlete is doing anything less valuable, or serving a lesser social function, than the more traditional areas of study. Personally, I don’t see much of a difference between a major in Sports Management and one in, say, Philosophy or History or any of the other liberal arts degrees that are notoriously the butt of jokes about their applicability to the job market. In measurements involving the bottom line, especially, I certainly find Jim Calhoun’s to be the more compelling argument.

Despite my sometimes less-than-stellar track record, I continue to find it fun to make predictions in public. I think this year is pretty easy to call (hint: Slumdog is going to win a shitload of awards, and deservedly so), but that remains to be seen, of course. Below are my predictions for who will win, as well as my personal choices if it were up to me to decide the winners (the “should wins,” if you will). We’ll see if I do better than I did last year (and at the very least, hopefully the format of this post is more clear than last year’s). I realize that a lot of this is redundant with my previous 2008-in-summation post, but this one is specifically geared towards the Academy Awards.

Category: Best Picture

Prediction: Slumdog Millionaire

My Pick: Slumdog Millionaire

I can’t really see this category going to any other nominee, although if I had to name a dark horse, I think Milk might have a chance in always liberal, always happy to make a political statement Hollywood. Don’t count on it, though.

Category: Director

Prediction: Danny Boyle, Slumdog Millionaire

My Pick: Danny Boyle, Slumdog Millionaire

Though I’ve not seen it, I would not be surprised if this went to David Fincher for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. My money’s still on Boyle, though.

Category: Actor

Prediction: Sean Penn, Milk

My Pick: Frank Langella, Frost/Nixon

There are three really outstanding performances in this category (the two listed above, plus Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler), one that was as much special effects as it was acting (Brad Pitt in Benjamin Button), and one that’s the indie darling that probably not enough voters have even seen for it to have a shot (Richard Jenkins in The Visitor). I think it’s nearly a toss-up between the “big three,” with my personal preference being for Langella’s heartfelt portrayal of Nixon, because I think it was the most difficult to pull off, but again I think that the Academy might prefer the more topical and politically-charged Penn role (and he’s certainly deserving).

Category: Actress

Prediction: Meryl Streep, Doubt

My Pick: I have to abstain, due to not having seen 4 of the 5 films

I think this is basically a two-horse race between Streep and Kate Winslet, and it could go either way.

Category: Supporting Actor

Prediction: Heath Ledger, The Dark Knight

My Pick: Heath Ledger, The Dark Knight

I think this is as much of an Oscar lock as there’s been in a long time. I do love RDJ’s performance in Tropic Thunder, though.

Category: Supporting Actress

Prediction: Penelope Cruz, Vicky Cristina Barcelona

My Pick: Marisa Tomei, The Wrestler

The dark horse potential surprise pick here is Viola Davis for her incredible single-scene performance in Doubt, but I think I’d rather see one of the two I’ve listed here take it. They’re neck-and-neck in my book, too, but the buzz has seemed to be centering more on Cruz, so I think that’s what the Academy will go with.

Category: Cinematography

Prediction: Slumdog Millionaire

My Pick: The Dark Knight

Benjamin Button might have a real chance in this category as well, if for no other reason than the fact that it might be the most visually ambitious film of the year. While I don’t think that Anthony Dod Mantle (Slumdog) would be undeserving, I really thought that Wally Pfister (TDK) broke some new and impressive ground.

Category: Original Screenplay

Prediction: Dustin Lance Black, Milk

My Pick: Martin McDonagh, In Bruges

Though I really think that In Bruges deserves at least some recognition, I could see this category going a few different ways. Mike Leigh wouldn’t surprise me too much with a win here for Happy-Go-Lucky (though, from the accounts I’ve heard, he wouldn’t be too happy to accept it, believing his film to be more of a collaborative, improvisational writing effort). We shouldn’t overlook the originality and biting social commentary of WALL-E, either, which I could see being rewarded here as well as in the Best Animated Feature category. I think this is another chance for the Academy to recognize Milk, though, and they’ll likely embrace it.

Category: Adapted Screenplay

Prediction: Simon Beaufoy, Slumdog Millionaire

My Pick: Simon Beaufoy, Slumdog Millionaire

I’m having a really hard time imagining any of the other nominees winning this category, but I think if I had to pick a dark horse it’d be Doubt because of the tight, dialogue-heavy script. I wouldn’t be betting against Slumdog here, though.

Editing: Editing

Prediction: Chris Dickens, Slumdog Millionaire

My Pick: Chris Dickens, Slumdog Millionaire

Lee Smith (The Dark Knight) might have a slight chance here, but really what this comes down to is the fact that this is Slumdog‘s year, and rightfully so. It was the most visually interesting, the most polished production, and the most effective storytelling of the year, and I think (along with pretty much everybody else) that it’ll be rewarded handily.

While I don’t think this was nearly as strong of a year as 2007 was, I do think that this should be a good Oscars ceremony, not only because it sounds like it’ll be a bit unique, but also because I look forward to seeing a celebration of Danny Boyle, one of my favorite filmmakers of recent times who is long overdue for some recognition and looks to be primed to finally receive some in spades.

I know I’m a little behind on this one, but here’s a video I think that everybody should watch. It’s 7 minutes from The Daily Show that near-completely summarizes the two prevailing points of view on the gay marriage issue, with Mike Huckabee playing the role of the social conservative with the slight Southern drawl, and Jon Stewart serving—as usual—as the person with the capacity for rational thought.

Huckabee keeps harping on what I think is the worst possible defense of anti-gay-marriage laws: that they are only exemplary of the will of the people. “If the American people are not convinced that we should overturn the definition of marriage,” he says, “then I would say that those who support the idea of same-sex marriage have a lot of work to do to convince us.” Stewart uses what I consider to be the most obvious retort to this type of thinking: “What if we make it if Hispanics can’t vote?” Is there any doubt that if such a measure were put to ballot in, say, Texas or Arizona or New Mexico, that it would pass? Or how about a vote to remove rights from black people in a state like Arkansas—wouldn’t you imagine that, if given the chance, the majority of the people in that state would happily assert their will in such a measure’s favor? (Am I guilty of broadly applying stereotypes here? Of course… but that doesn’t diminish the credibility of the point.) “Segregation used to be the law,” Jon reminds us.

Stewart also takes another stance that’s near and dear to me: “Religion is far more of a choice than homosexuality.” This, of course, is a particularly relevant comparison to make, considering the near-universal religious basis of anti-gay-rights movements as of late.

Huckabee runs through all of the go-to arguments against gay marriage rights. I think one of the most curious to me is when he suggests that were homosexuals given the right to marry, then “we would have to say to the guy in West Texas who had twenty-seven wives, ‘That’s okay.'” And without knowing the details of the story he seems to be referring to (and ignoring the obvious “straw man” nature of the point he’s trying to make in the first place), my initial reaction to that is: why shouldn’t it be? If 28 consenting adults have found an arrangement that brings them happiness, whose business is it to tell them they’re wrong? What about having 27 wives is intrinsically damaging to society, other than the fact that it’s not what white Christian Westerners have been told constitutes a “healthy family”? Perhaps that’ll be a fight that’s waged at some point in the (distant) future. (Or perhaps someone can tell me what I’m missing with this topic… “You watch too much Big Love” not being particularly enlightening.)

Obviously for now it’s all our culture can handle to try to address this current issue intelligently. When there are still people—leaders, in fact; governors, even—trying to assert “the difference between a person being black and a person practicing a lifestyle” it shows just how entrenched most of the thinking surrounding this issue is. Not to mention how fucked up.

Like most people who are into watching movies at home, I went out this week and bought The Dark Knight on Blu-ray. I’ve found it to be both an incredible use of the medium and simultaneously an awkward step in the format’s development. While I think there are some clever ideas on display with the extras, I find most of the BD-Live content to be pretty cheesy, and wonder if a significant amount of people would ever make use of such features. Primarily, though, this is a fantastic example of a beautifully-shot movie being exhibited in the best manner that current technology allows, and while that fact alone excites me, there is one aspect of this disc that really annoys me.

Christopher Nolan clearly feels that the IMAX format will be The Next Big Thing—not just figuratively, but quite literally—in film production and exhibition. It’s an interesting format, and has a lot of potential, but I feel that Nolan has gone about making use of it all wrong with The Dark Knight. (I’d actually intended to write a separate review of The Dark Knight: The IMAX Experience this past summer, but never got around to it… although a lot of my comments here apply equally to the theatrical IMAX release, which will be back in theaters next month.)

Unfortunately, only parts of The Dark Knight were shot in the IMAX format. The introductory bank robbery scene was filmed entirely in IMAX, but that is the only complete sequence that can make that claim. Throughout the rest of the film, the uses of IMAX are largely restricted to helicopter establishing shots, with a few brief action shots thrown in. It makes it feel like we’re paying to watch the filmmakers experiment with a new format, and in fact that’s partly true. But just because experimenting with shooting in IMAX is “a very fun thing to do” that doesn’t necessarily make it a good idea, especially when it comes at the expense of the cohesion of the movie.

To demonstrate the kind of high production value I believe in, I have taken video on my cell phone of my TV while watching The Dark Knight on Blu-ray and uploaded it to YouTube in order to illustrate my point:

If by some odd chance it’s not completely clear what you’re seeing there, I’ll summarize: most of the movie is presented in a 2.40:1 aspect ratio, which means it’s letterboxed when viewed on a 16:9 (1.78:1) HDTV. The IMAX scenes, however, take up the entire 1.78:1 viewing area, in addition to appearing a bit more crisp and defined, with better color balance, making them feel even “more high-def” than the rest of the movie. What this amounts to is that the black letterbox bars come and go throughout the movie, at times for only seconds at a time and several times during a single scene. It’s like the movie is continually informing you, “NOW YOU’RE WATCHING IMAX… now you’re not… NOW YOU’RE WATCHING IMAX!… now you’re not…”

Using a large format like IMAX is supposed to enhance the film-viewing experience; it’s not supposed to replace it. That is, it should make it more enjoyable—more impressive—to watch the movie, but it should not be, in itself, the source of that enjoyment, brashly calling attention to itself every chance it gets. Instead of the experience of viewing The Dark Knight—either in an IMAX theater, or in high definition in a home theater—being broadened by the occasional use of IMAX, it is instead detracted from by virtue of the fact that the format changes are jarring and obtrusive.

In short, it interrupts the suspension of disbelief.

This is a film that purports to Say Something, but unfortunately it believes that the assertion that you have said something is equivalent to actually saying it. The most prominent example of what I’m referring to: at the very end of the film, Commissioner Gordon (Gary Oldman) states that Batman will go on the lamb, because that’s what Gotham “needs right now.” This is a really dramatic way both to end your movie and to set up its sequel, but unfortunately nothing in the preceding two and a half hours has set up this moment: saying “he has to” is not a valid substitute for taking your character through a progression that convinces the audience that this is the case without having to actually state it. Likewise, I think that the premature use of IMAX makes for an ultimately dissatisfying experience, akin to teasing the audience with what might have been had the filmmakers only gone the whole way with it.

All of that said, though… damn, do those IMAX-filmed scenes look amazing on Blu-ray on a nice big HDTV. I’ll be excited to see the first major motion picture that’s filmed entirely in IMAX make its way to the format, so that it can be enjoyed without the distractions inherent to this type of partial use of it.

I would put the over/under on Cubs games that I watch each season at about 130, and the amount that I listen to on the radio (be it via XM or MLB.TV’s audio streams) right around 25. I don’t think I’m exaggerating to put my level of team-following at 95%; I’m a pretty big fan, and don’t miss many games, especially in a year like the one they’re currently having, which is not only one of the best during my lifetime, but one of their best ever.

I used to think that being this devoted to following a team was tough while living in Champaign, an area that is not really in the Chicago market but is at least close enough to get the Chicago channels. When we decided to move to California, I somewhat erroneously thought that all I would have to do to keep up my rate of game-watching was to get the MLB Extra Innings package along with my return to DirecTV that was made a necessity due to their monopoly on the NFL Sunday Ticket offering and my unwillingness to miss Bears games.

The most unfortunate part of returning to DirecTV—indeed, the reason I did not stick with them when moving to HD in the first place—is their terrible DVR software. After using it for about 3 months now, I think it may be even worse than the Insight/Comcast DVR that I used to put up with. One of the many frustrating things about it is that it will sometimes arbitrarily decide that a game should be blacked out for me, in some cases even after I’ve watched half of it. MLB’s blackout rules are infuriating enough without needing to be made worse by an overzealous adherence to them on the part of poorly-written software.

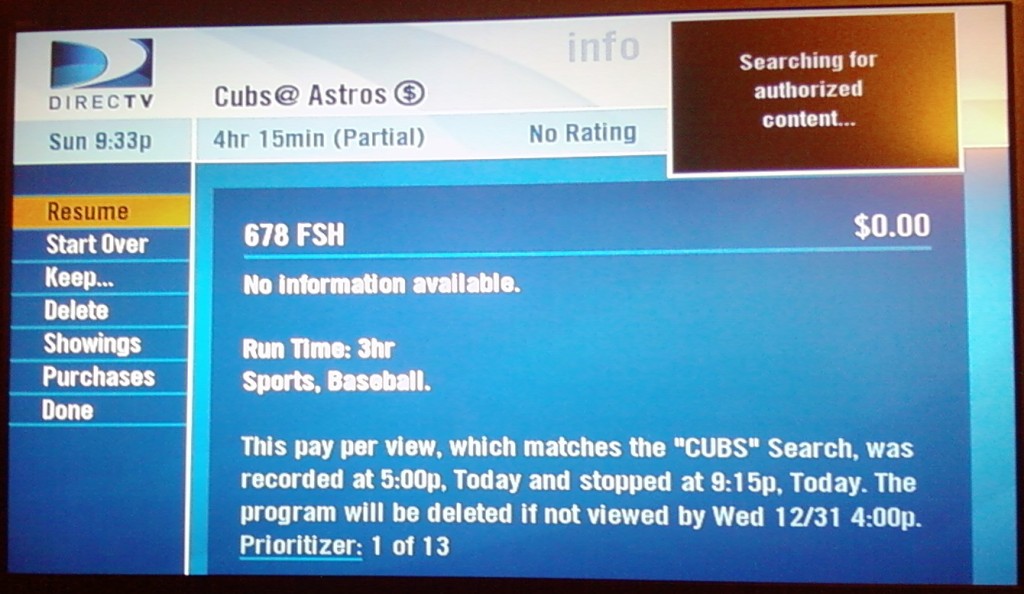

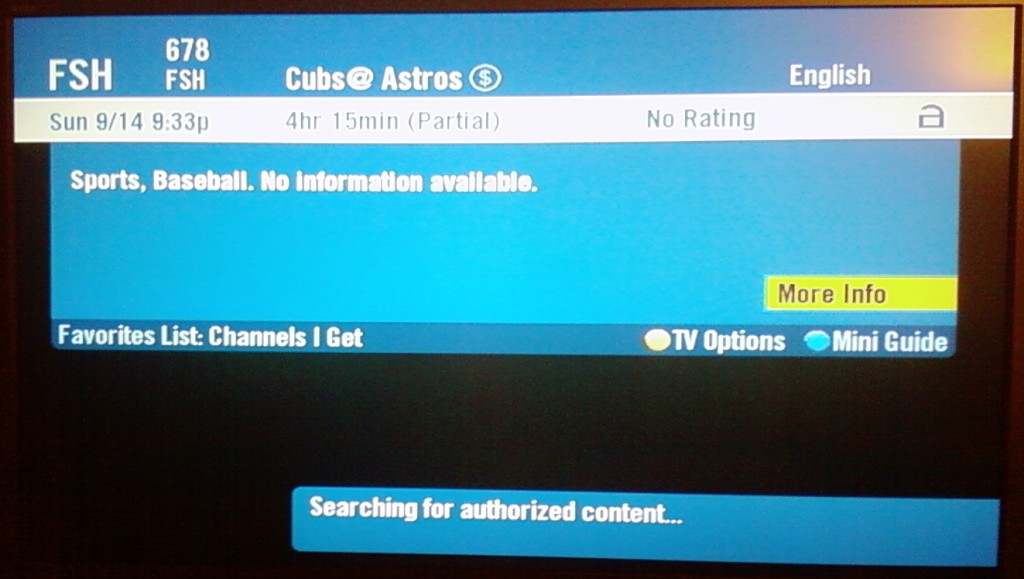

The single worst (and most unique) example of this came yesterday. As a result of Hurrican Ike ravishing the Houston area, the Cubs’ series with the Astros was moved to a “neutral site” in Milwaukee (at the park that Cubs fans affectionately refer to as “Wrigley North”—admittedly not the most neutral of options). Before going to a Sunday afternoon movie, I verified that my MLB package would get me the rescheduled game and that my DVR was intending to record it. After returning from the movie, when attempting to view the game—I prefer to be able to fast-forward through the commercials, so I watch most games slightly after the fact—I found this:

For some reason, DirecTV and my DVR had decided that this game was a pay-per-view event (albeit with a price of $0.00). It had recorded it anyway, thankfully, or so it appeared. When attempting to watch the game, all I got was this:

Unfortunately this is something I’ve contended with multiple times this season, usually the result of the stupid blackout rules (although thankfully such occurrences are few and far between). This particular occasion was made all the more upsetting, of course, by the significance of this particular game, in which my favorite player, the ace of the Cubs pitching staff, threw his first no-hitter—something I’ve been anxiously awaiting for the past few seasons, as Carlos Zambrano has shown no-hit stuff multiple times in recent years. Could anything be more frustrating for a sports fan?

Not wanting to repeat the experience, I listened to today’s game while at work, and was almost treated to an echoing performance from Ted Lilly. Not relying on my satellite service or their DVR software at all seems like the only reliable way to not be disappointed and angered by them.

Comments Off on No No-No For Me

Allow me to add to Mark’s rants about Fox Sports and their idiotic monopoly on Saturday daytime baseball broadcasts, and the idiocy of MLB that allows for it. Due to their agreed-upon blackout rules, I’m faced with another Saturday of not being able to watch my favorite team, despite the fact that I pay DirecTV over $200 per season in order to be able to do so.

Succinctly put on DirecTV’s explanation page, the policy goes as follows: “For every Saturday of the regular season, the FOX Television Network has the exclusive national rights to broadcast games up until 7:00pm ET (4:00pm PT).”

The reasoning behind this is pretty apparent: Fox wants to have the exclusive attention of any would-be Saturday-afternoon baseball fans, to maximize their advertising reach. I don’t think I’m in the minority when I say that this alone is completely stupid; I would say that I watch commercials less than 10% of the time I spend watching TV—and I watch a lot of TV. But it gets worse when you consider that there are other games that take place before 7:00pm ET on Saturdays that Fox makes no effort to broadcast, leaving fans with no options.

For example, today the Cubs-Pirates game started at 10:05am (this is a west coast phenomenon that I’m still getting used to, by the way, but find myself liking for the most part: I can get up, watch the game—if I’m actually able to get it, that is—and then have the entire rest of the day available, which is pretty nice). The Angles-Yankees game, which Fox is going to be broadcasting nationwide, will begin at 12:55pm. This means that it is extremely likely that the Cubs game will be over before the first pitch of the Yankees game has even been thrown. And yet, the “exclusivity” agreement means that the Cubs game is blacked out for everybody outside of the Chicago and Pittsburgh markets. It’s no wonder why so many people simply subscribe to DirecTV and then lie about moving to their market of choice. Not only does it save them the money of having to purchase the MLB Extra Innings package in order to follow their favorite team in the first place, but it also avoids these stupid blackout situations altogether. (The same reasoning goes, of course, for all of the other sports as well.)

It’s worth noting that ESPN has a similar agreement with MLB for their Sunday Night Baseball broadcasts. The major difference, though, is that there are no other games on Sunday nights. It could be said that days like today are the fault of the Cubs for scheduling a day game on a day when Fox’s blackout rules will be in effect, but why should Fox be allowed to dictate the entire league’s schedules, in the name of their greedy advertising bottom line?

I don’t think there’s any point where this will become an overstated sentiment: Fox Sports sucks. I’ve complained about it before, and I’m sure I’ll do so again.

UPDATE: A decent solution that I forgot to mention is to just leave the house and listen to the game in the car, which is what I ended up doing (we had somewhere to go anyway). XM includes every Major League game, with no blackouts, as part of their standard service. It’s not the same as watching it on TV, but Pat and Ron are always enjoyable, and it’s definitely better than sitting at home cursing Fox while staring at a blank screen showing error code 727.

Some sad news quietly came out today without much press coverage of it, but I think it warrants recognition: Both Roger Ebert and Richard Roeper, of “At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper,” have opted to part ways with Disney and the show that’s borne their names since 2000 (and bore the names of Gene Siskel and Ebert for well over 20 years prior to that). It’s been a sad time for this show the past couple of years as it was, with Roger’s health not allowing him to appear. Still, Roeper has done a decent job of carrying the torch in his absence, and the guest reviewers have been generally enjoyable.

Things had been going downhill for a while, including Disney’s abrupt ending of the use of the trademarked “Thumbs™” and resultant blame game played between them and Ebert. Hopefully there’s a Disney-less future for this format. The good news is that the huge archive of episodes and individual reviews remains online, and should remain available in the future, barring any further fallings out.

On a positive Ebert-related note, an Ebertfest documentary recently premiered on the Big Ten Network. It’s well worth checking out—hopefully it’ll be replayed (keep an eye out for “Illinois Campus Programming” on the schedule).