Video games can be a lot of fun. Millions of people–young and, increasingly, old–enjoy them as a true form of entertainment, storytelling, and sometimes even artistic expression. Gamers have long enjoyed assuming the persona of an on-screen hero or heroine, allowing themselves to get wrapped up in a fantastic world where their imaginations can run wild and the impossible is possible. Until recently, though, it was typically pretty clear what was meant by a player “assuming the persona” of his or her virtual alter-ego.

With the advent and exploding popularity of the Guitar Hero series of games, the line has been blurred. Part of the problem is one of language: we “play” a video game and we “play” a musical instrument, but these are normally two different things. It then makes it hard for a Guitar Hero enthusiast to not sound like he takes himself entirely too seriously when he talks about the songs he’s been “playing.” But the problem is compounded by the fact that many Guitar Hero enthusiasts do, in fact, take themselves entirely too seriously (more on that in a bit).

Another aspect that blurs the line between playing a game and playing an instrument is the very feature that has most likely accounted for the series’ success: the novel guitar-shaped controllers it employs. As opposed to using the standard console controller, these allow one to assume roughly the posture, hand position, and motions (albeit all on a greatly simplified basis) of somebody who is actually playing a guitar. This, in turn, makes it easier for the player to convince himself that what he is doing while playing the game has some relation to the act of playing guitar. Compare the two activities:

Another aspect that blurs the line between playing a game and playing an instrument is the very feature that has most likely accounted for the series’ success: the novel guitar-shaped controllers it employs. As opposed to using the standard console controller, these allow one to assume roughly the posture, hand position, and motions (albeit all on a greatly simplified basis) of somebody who is actually playing a guitar. This, in turn, makes it easier for the player to convince himself that what he is doing while playing the game has some relation to the act of playing guitar. Compare the two activities:

| Playing Guitar | Playing Guitar Hero | |

|---|---|---|

| Playing position | Sitting down with guitar rested on lap, or standing up with guitar strapped to torso | Sitting down with controller rested on lap, or standing up with controller strapped to torso |

| Left hand | On fretboard on neck of guitar; presses strings to change their pitch | On buttons on neck of controller; presses buttons to “play” various notes |

| Right hand | Over sound hole (on acoustic guitars) or between pickups (on electric guitars); picks or strums strings to play notes or chords | On strum bar on body of controller; move back and forth vertically to “strum” or “pick” |

| Typical practice space | Living room, bedroom, or basement | Living room, bedroom, or basement |

| Learning curve | Very steep | Shallow |

| Time required to achieve mastery | Several hours a day for many many days; becoming a master takes several years of intense practice | Several hours at a time over many gaming sessions; becoming a master takes several months of repetitive practice |

| Cost | Cheap guitars can be had for $100-$200; electrics require amplifiers; ongoing upkeep (regularly replacing strings, etc.) | Under $100 |

The main difference lies in the initial startup cost, and in the fact that it’s much easier to pick up a Guitar Hero controller and start playing right away than it is to do the same with a real guitar. After that, though, becoming good at either activity requires sitting around for hours on end playing the same songs over and over and over again until memorization and/or mastery has occurred. It’s in this regard that I think the activity of playing Guitar Hero is baffling to some, myself included: Why spend all of that time and effort simulating the act of learning to play guitar, rather than actually learning to play guitar?

It goes beyond that, though. The next evolutionary leap of the Guitar Hero series is Rock Band, which takes the concept to the next level. Instead of only one or two players using fake guitars to “play” the lead and/or bass guitar parts, there is now additionally a “drum” part and a “singing” part (as well as a new $170 price tag). The packaging for the game invites players to “start a band” and “rock the world.” Unfortunately, a lot of people have taken this entirely too literally. A lot of the explanation for the whole phenomenon, I think, can be attributed to the fact that most people don’t really understand what is involved with playing the instruments represented in these games. It was bad enough when the games’ makers just oversimplified what it means to play a guitar; now they’ve added two additional parts that almost everyone thinks they can do without any sort of training, despite the fact that singing and drumming are just as musically involved and require just as much instruction, practice, and perseverance as the guitar does.

It certainly doesn’t help when reviews of Rock Band say ignorant things like, “while learning to play a plastic guitar gets you nothing but higher scores on a game, getting good at the drums in Rock Band will actually give you some drumming skills in real life.” Statements like this have the dual effect of demonstrating the reviewer’s ignorance of what actually constitutes “drumming skills” while also misleading would-be drummers into thinking that Rock Band‘s lame excuse for a drum kit and drum charts will be a sufficient substitute for (or precursor to) learning the real thing. Some reviews, thankfully, are a bit more honest with their readers, but they still exaggerate the relation between the Rock Band drum kit and actual drumming: “With the exception of the drum parts, which are somewhat realistic, Rock Band substitutes reflexes for musicianship.” Yes, the drum parts are “somewhat realistic,” but in exactly the same way that the guitar parts are “somewhat realistic,” and no more. It is sad that people who have obviously never played drums before deem themselves worthy to comment on the experience. While it seems commonplace for most articles about these games to accept–and occasionally poke fun at–the lack of realism inherent in the guitar controllers, they simultaneously make the mistake of presuming the existence of a level of realism in the drum controller that is just as equally absent.

It certainly doesn’t help when reviews of Rock Band say ignorant things like, “while learning to play a plastic guitar gets you nothing but higher scores on a game, getting good at the drums in Rock Band will actually give you some drumming skills in real life.” Statements like this have the dual effect of demonstrating the reviewer’s ignorance of what actually constitutes “drumming skills” while also misleading would-be drummers into thinking that Rock Band‘s lame excuse for a drum kit and drum charts will be a sufficient substitute for (or precursor to) learning the real thing. Some reviews, thankfully, are a bit more honest with their readers, but they still exaggerate the relation between the Rock Band drum kit and actual drumming: “With the exception of the drum parts, which are somewhat realistic, Rock Band substitutes reflexes for musicianship.” Yes, the drum parts are “somewhat realistic,” but in exactly the same way that the guitar parts are “somewhat realistic,” and no more. It is sad that people who have obviously never played drums before deem themselves worthy to comment on the experience. While it seems commonplace for most articles about these games to accept–and occasionally poke fun at–the lack of realism inherent in the guitar controllers, they simultaneously make the mistake of presuming the existence of a level of realism in the drum controller that is just as equally absent.

Amplifying the problem is the fact that the Rock Band drum parts–which, like the guitar parts, come in varying difficulty levels–are not a good way to teach somebody to play the drums, despite the fact that the possibility to use them for that purpose might actually exist. This is probably what leads to the assumptions on the part of most reviewers that progression through the game’s levels of difficulty is equivalent to progressively learning more about how to actually play the drums, but again that only shows the reviewers’ ignorance and not the achievement of the game in that regard.

My personal experience with these games is, admittedly, very limited. I find it very hard to get used to “playing” the “notes” ahead of the actual song; one thing that nobody seems to mention is that there is a slight but significant delay between when you “strum” the guitar controller or hit one of the pads on the drum controller and when the game registers the “note” being “played.” This does not teach you to play the song or to even come close to rhythmically approximating it on a basic level; rather, it is simply a test of reflexes, as previously mentioned, combined with memorization at the more difficult levels. It is not in any way musical, at least no more so than is tapping on your lap or strumming an air guitar. In fact, I’ve played Guitar Hero with both the guitar controller and a standard Xbox 360 controller, and found the musical experience I derived from the two to be equivalent.

It gets really weird when you consider that people actually put on “concerts” involving playing this game on a stage. There is even a smoke and light kit set to be released soon. And some people have taken it even further than that, combining the fake instruments with real ones in order to give them a more realistic look for their “performances.” This begs the question of why not just actually learn the instrument? even more, and makes for an even more ridiculous example of just how far people will go to keep themselves firmly planted in the world of a video game, no matter how much they attempt to emulate the world that the video game is supposed to be simulating. It’s additionally yet another case of the relevant South Park episode coming true in a way that’s as sad as it is hilarious.

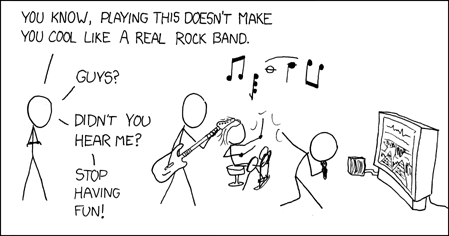

So am I just such a curmudgeon that I can’t stand the thought of people playing a quasi-musical video game and enjoying themselves while doing so, as the xkcd comic implies?

The answer, of course, is no; “stop having fun” is not my point. My point is, honestly, that I worry about what this means for our culture, that it seems we can no longer be troubled to actually take up any hobby that doesn’t have a score attached to it. More than that, though, it’s that we seem to have moved beyond the fantasy world of video gaming and into the realm of games as substitutes for their real-life counterparts. I’ve been known, for instance, to play a game called Golden Tee from time to time, but nobody has ever mistaken that for an actual round of golf, and nobody has ever claimed that learning Golden Tee makes you a better golfer. It seems that day may not actually be far off, though, and I wonder what that would mean for the sport of golf when the next Tiger Woods gets addicted to the video game instead of the actual sport. Likewise, what does it mean when there are children who are considered to be Gods of Guitar Hero? Are these the would-be rock stars of tomorrow, choosing to pursue a perfect score in place of writing a future hit?

Mostly, though, this whole phenomenon gives me that sadness you feel when you see others getting cheated out of what you believe to be a worthwhile experience that you yourself have had. It’s like when somebody tells you they recently purchased a new HDTV, but then you find out that what they bought is a low-end Vizio and they’re still watching standard definition content stretched horizontally. It’s somebody telling you they’re a Linux expert, only to then divulge that their experience comes from using Ubuntu a couple of times. It’s somebody telling you they’re a hardcore programmer when all they’ve ever coded in is Java. None of these people are lying when they make these claims; they’re just missing the point of the experience by only going halfway with it.

And that’s how I feel about the Guitar Hero series of games, and especially Rock Band: Sure, it’s fun to play, and it might even help drive you to get better by having a simple scoring system to use as a yardstick. But when you confuse it with an approximation of that which it is meant to imitate, you’re missing the point of both.

The Largo film that I previously wrote about is featured in an article in the current issue of Filter magazine, available now. Andy, my friend behind the film, had this to say about it:

Check out the new issue of Filter magazine (w/ David Byrne on the cover), at newsstands and bookstores now through February, for a great article on Largo and my upcoming concert movie. The article is called, “Exalting the Artistic Moment: The Meaning of a Place Called Largo.” For those of you who aren’t already familiar with the club it’s a good primer on its history and what makes it special.

The article also features a lot of stills from the movie, a great shot of Elliott Smith by photographer Autumn de Wilde

, and interviews with myself, club owner & co-director Mark Flanagan, and performers Jon Brion, Aimee Mann, Mark Oliver Everett (E from Eels), Zach Galifianakis, Tom Brosseau, Grant-Lee Phillips, and Paul F. Tompkins.

The film sounds like it’s on track for its targeted February 2008 completion date. Hopefully I’ll be headed out to LA around that time to see the first screening of it there, followed by TriBeCa in late April/early May. Pretty exciting.

Comments Off on Largo Pub

Largo is a club in Hollywood, the kind that you assume locals tell their out-of-town guests about when asked for some “best kept secrets.” The owner, Flanny, is one of those LA staples who people in the know all know. The club is a sit-down music venue where you’re as likely to encounter an artist you’ll recognize in the crowd as you will on stage. Flanny–a long-time music booker and promoter–is big on presentation and ambiance, and has no-chatting and no-cell-phone-use rules during all shows; somehow this works for him, although with other establishments it’d likely come off as pretentious and annoying. Largo is the kind of place, though, where you want to just sit back, enjoy the food (all of which is good, by the way), have a few drinks (the only things on tap are Guinness and Bass), and most of all, enjoy the music.

Whenever I visit my lifelong friend Andy who lives in LA, hitting Largo is always my first request for things I’d like to do while there. I’ve been lucky enough to see Jon Brion a couple of times (indeed, the first such experience had such an effect on me it warranted being the subject of one of four total posts I ever managed to make on my LiveJournal). We always have a good time, and I always leave feeling a little more cultured, having seen some music I probably wouldn’t have been exposed to otherwise (the most recent was Nikka Costa, who was just fantastic).

For the past couple of years, Andy has been spending most of his weekends collecting footage of Largo’s stable of performers doing music, comedy, and other forms of performance art on the club’s small stage. The last few times I’ve been out to visit him I’ve been privileged enough to watch the film centered around the venue that he’s been working on as it comes together. He recently launched a promotional site for the film that shares the venue’s name, in anticipation of completing and releasing it in the very near future. There’s a trailer that he’s put together to give a glimpse at what the finished product will be like; think of it as a concert film where the setlist reads like a “best of” compilation of musicians, comedians, actors, and assorted guest appearances from the club over the past year or two.

I’m anxiously awaiting the film’s conclusion, and can’t wait to see it on a big screen as soon as the opportunity arises. Andy knows I’ll be there for its first screening no matter the circumstances.

Comments Off on Largo

When I was 15, my family moved to Naperville. A year later, a family moved into the house a few down from ours, and we found out that they had a son, Brant, who was about my age and was going to be on the drumline (which I was also a part of). I met him shortly after they moved in, and we more or less immediately became friends. That was about 12 years ago now, and Brant and I don’t see each other as often (he now has two children keeping him very busy), but we keep in touch and stay caught up as much as possible.

The first thing I learned about Brant was that he was an incredibly talented drummer. Early in our friendship he was proud to show off videos and demo tapes from the band he’d been a part of back in the St. Louis area, where his family had moved from. I’ve always supported him in his various musical endeavors, from high school on. These days, he’s in a band called Veritae, based out of the Chicago area.

A little over a year ago, Brant contacted me about helping him set up a Web site for his band, and I happily agreed to help in any way I could. What I soon found out, though, was that this was not to be a “normal” Web-design endeavor. As part of the deal his band had made with their producer, they got Web hosting along with their studio time. This wasn’t just Web hosting, though; it included a Flash-based site creation tool called Habitat that I would be using to create their site.

It’s worth noting at this point that generally when I make a Web site, I do it using one tool, and one tool only: vi. So a completely Flash-based graphical tool that designs a Flash-based Website for you is about as much of a polar opposite from my preferred style as you can get. This causes, unsurprisingly, quite a bit of frustration on my part. I’m sure some people find the idea of this Habitat tool to be a great idea; even I can admit that it’s novel. I’m certainly not alone, however, in my criticisms of Flash.

It’s been an interesting experience, then, trying to keep the band happy with the site, while at the same time loathing myself for using something and creating something that I consider to be a great example of everything that is wrong with the Internet. It loads slowly, uses way more bandwidth than necessary, is completely inaccessible, and requires a browser plug-in in order to view any of the content on the site. The one thing the Habitat guys deserve credit for is making a Flash-based site that is bookmarkable. However, this was at the cost of additional load times when you traverse between sections, so even that can’t be viewed as a total positive.

I have to remind myself, though, that this is the music industry, and flash (with a lower-case ‘f’) and style can make all the difference in the world when trying to catch people’s attention. This is the same industry that uses MySpace as of late as its primary means of independent publicity.

After several months of inactivity, there was a crash with the band’s site, and I’ve spent some time yesterday and today recreating it. I’m not happy with it, and still have several gripes, but feel it my duty nonetheless to advertise Veritae’s Web page and drive any traffic I can to their site.