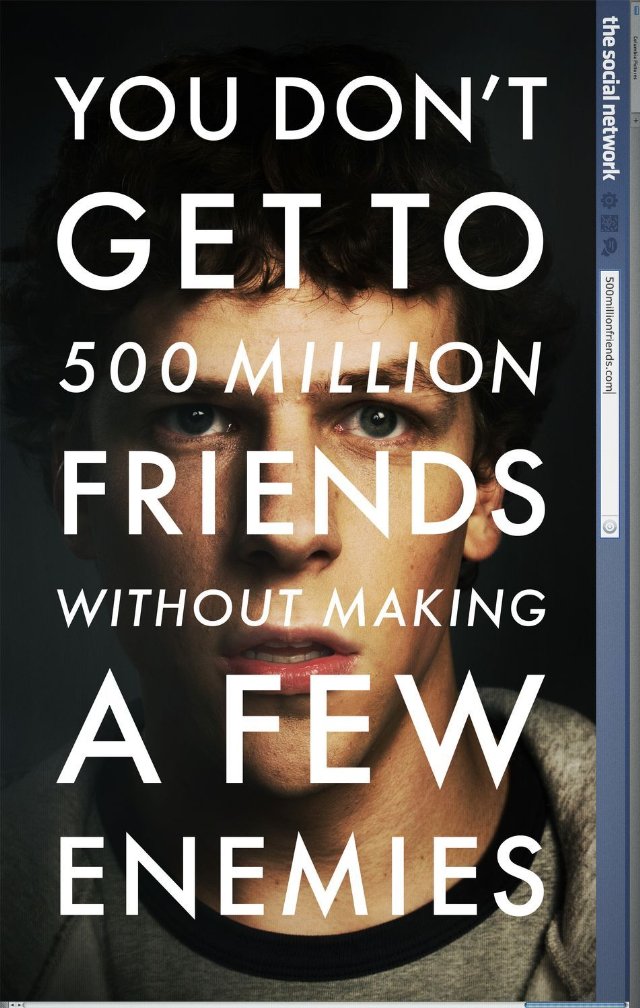

Status: In theaters (opened 10/1/10)

Directed By: David Fincher

Written By: Aaron Sorkin

Cinematographer: Jeff Cronenweth

Starring: Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, Justin Timberlake, Armie Hammer, Rashida Jones

Imagine being on the UHF program “Stanley Spadowski’s Clubhouse” and winning the opportunity to drink from the firehose, only instead of water coming out, the hose spews dialogue into your face. That’s a lot what the experience of watching The Social Network can feel like. This movie is full of words, coming at you at a mile a minute at almost all times. Jessie Eisenberg, as the onscreen personification of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, does the bulk of the firehosing. He sometimes sounds like he’s rushing to spit out his lines in record time, but by the end of the film’s opening scene, you’re already used to it and totally engrossed. It takes balls to write a movie like this, and a lot of talent, too. In less-capable hands it’d come out feeling like a wordy, jumbled mess, but Aaron Sorkin is more than capable. His screenplay, which I’ve read came in at 160 pages (a typical 2-hour movie, which this is, would be more around 120), is jam-packed with dialogue spouted by fast-talking characters, and it drives the story in almost unbelievable ways.

The sniff test for me for any technology-based movie is how it deals with the specifics of its technologies, and The Social Network passes with flying colors. While Sorkin lets himself get a little carried away, particularly during a scene where Zuckerberg “interviews” interns by putting them to a hacking test while constantly feeding them shots, for the most part his characters’ dialogue is legit. We see Zuckerberg live-blog the creation of Facemash, Facebook’s predecessor, and his voice-overs describing his use of PHP, perl scripts, and wget to acquire the classmate pictures he needs from shoddily-configured Apache servers hold up. Sorkin has done his research, and it’s no surprise; you throw this much information at an audience at such a rapid pace for two solid hours, they’re going to smell it if you’re just trying to sneak stuff past them.

Based on the legitimacy of the computer-related dialogue, I have to believe that the same amount of research went into the court records that form the basis of The Social Network‘s narrative. The story is told from the perspective of two separate depositions, involving the two major lawsuits that were brought against Zuckerberg after Facebook started to take off.  The first comes from his best (and only) friend, Facebook co-founder and original CFO Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield). The second is from Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss (Armie Hammer’s face on both twins, with Josh Pence providing Tyler’s body). The “Winklevi,” as Zuckerberg refers to them, had devised a website called Harvard Connection (later ConnectU) and hired him to provide programming assistance. They claim that he stole their idea and cut them out of the loop when he launched his own website. Saverin, on the other hand, claims he was unfairly squeezed out of his ownership position in the company—it was his initial $1000 investment that got it off the ground.

The first comes from his best (and only) friend, Facebook co-founder and original CFO Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield). The second is from Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss (Armie Hammer’s face on both twins, with Josh Pence providing Tyler’s body). The “Winklevi,” as Zuckerberg refers to them, had devised a website called Harvard Connection (later ConnectU) and hired him to provide programming assistance. They claim that he stole their idea and cut them out of the loop when he launched his own website. Saverin, on the other hand, claims he was unfairly squeezed out of his ownership position in the company—it was his initial $1000 investment that got it off the ground.

From the retrospective view of these depositions, we get three versions of the story: Saverin’s, the Winklevoss’s, and Zuckerberg’s own account. The Rashomon style of storytelling Sorkin employs works well for two reasons. First, it gives a natural excuse to jump around in the story, to skip to the interesting parts of Facebook’s tumultuous early years. Second, it provides a clever way to avoid any claims of libel or of fabricating details; in getting three different points of view on the events, things are left just ambiguous enough to avoid being slanderous.

That’s a good thing, because The Social Network doesn’t exactly paint a pretty picture, particularly of Zuckerberg. It does, however, give him a fair shake; he’s depicted as an insanely driven kid who happens to have a knack for knowing what people want out of the new online experience he’s trying to create. But like most stereotypical computer geeks, he lacks in social skills, to the point of ignoring the desires or feelings of anybody else he’s involved with. He’s smart, that’s clear, though I’m not sure why he’s always referred to as a “programming genius”—Facebook is the most standard, typical, and simple website you could make, technology-wise. But that’s not where Zuckerberg’s genius lies; it’s not how he does it that’s impressive, it’s the instinct he has for what to create that makes Facebook an instant success.

That’s a good thing, because The Social Network doesn’t exactly paint a pretty picture, particularly of Zuckerberg. It does, however, give him a fair shake; he’s depicted as an insanely driven kid who happens to have a knack for knowing what people want out of the new online experience he’s trying to create. But like most stereotypical computer geeks, he lacks in social skills, to the point of ignoring the desires or feelings of anybody else he’s involved with. He’s smart, that’s clear, though I’m not sure why he’s always referred to as a “programming genius”—Facebook is the most standard, typical, and simple website you could make, technology-wise. But that’s not where Zuckerberg’s genius lies; it’s not how he does it that’s impressive, it’s the instinct he has for what to create that makes Facebook an instant success.

What the movie really boils down to is a story about ego and greed. When Zuckerberg meets Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), one of the founders of Napster, he adopts the angst-filled party-boy’s worldview, happy to give venture capitalists the finger (literally) because he knows that they need him more than the other way around, and he revels in flaunting his newfound status. He turns his back on his friend not out of spite, but out of ambition, and the way Sorkin’s screenplay handles the relationship between Zuckerberg and Saverin—showing both perspectives, eliminating any questions of malice—is more measured than the version in Ben Mezrich’s book The Accidental Billionaires—the film’s primary source—which is told a bit more subjectively from Eduardo Saverin’s point of view.

There are two things that I found really refreshing about The Social Network. For one, although it’s a big-budget movie (and surely an awards-season contender), it doesn’t feel like a typical “tentpole” release. David Fincher’s direction is elegant and classy; the performances are highly characterized, but none feel over-exaggerated; there are great special effects, but you’d never realize it from watching the movie; even the score, by Trent Reznor, appropriately sets the pace and tone without drawing unnecessary attention to itself.

The other thing, the thing I really liked, is how the film makes no attempts to depict Facebook as super-relevant to culture in general, or to over-state its importance. It’s telling a story about a kid who found success at a young age and let it get to his head, and it leaves things at that. Yes, the success he achieved is by coming up with something that seemingly everybody wants to use—and use a lot—but we never get any speeches about some supposed importance of the website itself. It’s just the vehicle by which these characters embark on their journey. (Timberlake’s Parker does get a little carried away with the overarching cultural significance of what they’re doing, but it’s in character for him, it’s not the film itself telling us we should recognize this supposed “greatness.”) What’s amazing, and impressive, and downright enjoyable, is that The Social Network resonates more because of this. It’s a timely story, yes, but it’s one about truths of human nature that apply universally.

Comments Off on Baby You’re a Rich Man

With my review of The Town posted, I’m more or less caught up on my reviews, with a small exception: I’ve made the executive decision to ignore two movies I saw earlier this summer, because it’s just been too long since they were out, and I doubt anybody cares to read about them anyway. But here are really, really brief thoughts on them, in the interest of being thorough:

- The Other Guys was a pretty funny, if standard, Will Ferrell comedy. Like most of the Ferrell-Adam McKay collaborations, it goes a too bit far when it runs out of jokes (in this case, Ferrell’s “Gator” alter-ego), but it holds its own. It actually made me feel bad for Kevin Smith, who tried for a similar type of thing with Cop Out but failed pretty miserably. The most impressive thing about The Other Guys, in fact, was that in parodying an action movie, it actually ended up having some legitimately good action scenes. It’d make for a good rental.

- The Switch, on the other hand, was really bad. It sucks to say that, because Jason Bateman is usually such an enjoyable actor to watch, but here he’s all wrong for the role. The premise of the movie is completely ludicrous; if there’s one thing I know, it’s drinking, and this isn’t how it works. Not only does Bateman’s character get black-out drunk and yet still muster the ability to spank one out with minimal “material” to aid him, but he also somehow magically recalls what happened that night 7 years later. Throw in a terrible (though cute) child actor and Jennifer Aniston in another generically Jennifer Aniston role, and there’s not much reason to check this one out.

In more recent news, I’ve had the opportunity to put up a few reviews over at GTBP, so check them out if you’re interested:

- Devil (

) – In theaters now; Opened 9/17/10

) – In theaters now; Opened 9/17/10 - Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (

) – In theaters now; Opened 9/24/10

) – In theaters now; Opened 9/24/10 - Secretariat (

) – Opens next Friday, 10/8/10

) – Opens next Friday, 10/8/10

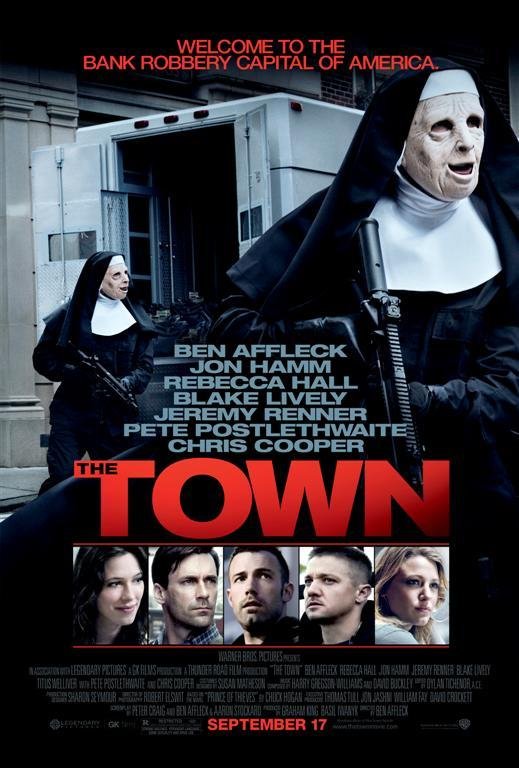

Status: In theaters (opened 9/17/10)

Directed By: Ben Affleck

Written By: Peter Craig and Ben Affleck & Aaron Stockard

Cinematographer: Robert Elswit

Starring: Ben Affleck, Rebecca Hall, Jon Hamm, Jeremy Renner

Doug MacRay (Ben Affleck) is from Charlestown, an area of Boston known for the amount of bank robbers per capita it sports. Doug’s a prime example: his father (Chris Cooper) was a stick-up man, and Doug is following in the family tradition. There’s a scene in The Town where Doug visits his old man in prison—it’s Cooper’s only scene in the film, but he’s amazing in it, as he always is—and it really drives the point home that not only is crime a way of life for these people, but there was never really any other option to begin with. The younger MacRay was good at hockey; he even got drafted. But the lifestyle he grew up around is like a magnetic force that he couldn’t pull away from.

Doug’s best friend is James Coughlin (Jeremy Renner). Jim did 9 years for murder, and now that he’s finally out, he’s itching for action. Renner is nearly the highlight of the film in this role; he’s a cocksure, tightly-wound spring, and you’re waiting for him to burst at any moment. His performance in The Hurt Locker was no fluke—he’s an actor whose portrayals have the kind of depth that sucks you in, making you root for him even though you know you shouldn’t be.

Doug has a history with Jim’s sister Krista (Blake Lively). She’s the kind of townie girl who I wish I could say I wasn’t all too familiar with: a single mother with multiple substance-abuse problems, her kid has an idiotic name (“Shine” in this case) and you know she’s unfit to parent. Yet she, too, draws your sympathy. Blake Lively really shocked me in this role; she doesn’t play Krista as just a fine piece of ass—though she is, by all means, that—but also as a conflicted person who’s trying to find her own version of what’s right, and just can’t seem to get her sights set correctly.

There’s a theme here, and it’s no coincidence: The Town is a strongly character-driven piece, despite what its facade of being a cops-and-robbers movie might lead you to believe. It’s good at that, too, mind you—particularly with Jon Hamm heading up the side of the good guys as an FBI agent hot on the trail of Doug and Jim’s crew. But what sucks you in, what makes you care, is that the performances are across-the-board spectacular, and the characters are all so well-written that you feel like you know them right from the start, and you’ll root for them throughout.

There are three big heist scenes in the film, and they offer a nice progression. They also serve to bookend the story and anchor it in the middle with reminders of what these guys are really all about. They’re shot and edited with the virtuosity you’d come to expect from a director known for doing this type of thing, but here it’s Ben Affleck at the helm, and he owns it. Affleck loves Boston, and we all know that; there’s the expected aerial establishing shots, lovingly framed to show his home town in its best possible light. We see the Bunker Hill Bridge, and that too anchors the film, reminding us not only of the town that these characters can seemingly never leave, but also serving as a strong and effective metaphor for their plight in general.

The complication to this story—the rub, as it were—comes when Doug falls in love with the manager of the bank his crew robs in the film’s opening sequence. Claire (Rebecca Hall) is what the locals call a “toonie”: an out-of-town yuppie who’s come to Charlestown and doesn’t fit in, not that she’s really trying to. Doug sees her as his chance at escape, an opportunity to find a different life and to have somebody to find it with. For the character to work, you have to sympathize with him, and it’s hard not to: Hall plays Claire not as a naive country girl, but as a savvy and likable woman who just happens to have had some bad luck, and is willing to give something different a shot as a result. She’s not terribly far removed from Vicky, but Rebecca Hall is a versatile enough actress to use the same sort of down-to-earth charm we saw Woody Allen draw out of her so well, and add some additional depth to it.

Affleck the director loves Hall, too—maybe not as much as he loves Boston, but pretty close. He’s infatuated with shooting her in close-up, accentuating her toothy smile and drawing the audience in to the appeal his character sees in her. It’s an effective directorial style, and even if he does overuse it a bit, seeing Hall’s pretty face fill the frame provides for a nice contrast to the more chaotic action sequences.

I thought that Gone Baby Gone was a well-crafted film featuring great performances from a terrific cast; it’s impressive that Ben Affleck has already been able to progress even beyond that achievement with The Town. It’s another well-crafted film, one that also showcases the work of an extremely talented collection of actors. In their sophomore effort, though, Affleck and co-writer Aaron Stockard (working from a screenplay by Peter Craig) have upped their game; the story is more ambitious and more cohesive, and Affleck’s direction has risen to the challenge. This time he casts himself as the star, too, as if we needed any further evidence that the guy can do it all.

I’ve got a couple of catch-up reviews to get to, but before doing so I wanted to revisit a couple of the thoughts I’d previously posted on Christopher Nolan’s Inception, in light of some insights I’ve gained from reading the shooting script.

- I’d mentioned, in my confusion of how the dreams work, that Arthur tells Saito it’s his second-level dream they’re in. Arthur is shot, and yet the dream continues. This seems to have been a case of me incorrectly recalling the specifics of what was going on; in the script, it’s actually Nash who tells Saito they’re in his dream. This makes more sense, of course, as it is Nash who screwed up the detail of the carpet, and subsequently gets punished for it.

- I was also unclear as to how the roles of dreamer and architect work and interact with each other. In fact, during the planning stages of the mission, Nolan mentions on two separate occasions that Ariadne is showing the details of her design to the dreamers in the background, while Cobb is explaining the mission in the foreground. The first instance is in New York (Yusuf’s dream):

EXT. NEW YORK STREETS—DAY The team are in the middle of a DESERTED intersection. Ariadne is showing Yusuf aspects of the geography. EAMES We could split the idea into emotional triggers, and use one on each level.

And the second is in the hotel (Arthur’s dream):

INT. DESERTED HOTEL LOBBY—DAY The team sit on the steps of the large marble lobby, debating. Ariadne is showing Arthur the lobby.

This was either lost in editing, or it was so subtle in the finished film that I completely missed it, but it does explain a bit, and fills in a gap that was annoying me. (Now the only thing that annoys me about the above is how Nolan, a Brit, uses collective nouns: “The team are…”)

- I agreed with an opinion piece I’d referenced that the bizarre narrow alleyway in Mombasa may have been the clearest sign that the entire movie occurs within Cobb’s dream. While Nolan doesn’t spell it out explicitly in his screenplay, he does describe the way the crowds look at Cobb as he runs through the streets of Mombasa in the same manner he describes the “projections” looking at Ariadne during her dream-tutorial. On the folded streets of Paris:

As they walk, Ariadne notices more and more of the projections STARING at her.

Then on the bridge:

People crossing the bridge STARE at Ariadne. Several of them BUMP her shoulder as they pass.

And finally:

Cobb says nothing. He stands there, staring at Ariadne. PEOPLE around her stop and look at her, hostile. COBB Look, this isn't about me— Cobb reaches for Ariadne's arm, turns her to him– ARIADNE Is that why you need me to build your dreams? A passerby GRABS Ariadne's shoulder– COBB Leave her alone— More of the crowd join in, PULLING at Ariadne, holding her arms open– Cobb PULLS people off– the crowd PUSHES him away–

By comparison, when Cobb escapes from the cafe in Mombasa:

Cobb stands up, PUSHES into the crowd– faces PEER at him– he moves, trying to blend– a SECOND BUSINESSMAN is there.

And finally, when Cobb finds the alleyway:

Cobb LOOKS left, right... CUTS LEFT into a narrow, CROWDED alley– the alley NARROWS TO A DEAD END. Faces in the CROWD start to watch Cobb– PEOPLE start to SURROUND him– Cobb looks back the way he came– the two Businessmen are there, GUNS DRAWN–

Maybe I’m looking too hard at this, but to me both sequences have the same tone of writing. Particularly in Mombasa, it seems Nolan is going to great lengths to draw attention in his script to the behavior of the crowds, which is the same as the behavior of projections that “feel the foreign nature of the dreamer” and attack “like white blood cells fighting an infection.”

- The line I couldn’t catch that Arthur mumbles after losing a guard on the Penrose stairs is, “Paradox.”

- Perhaps the most telling thing I learned from reading the Inception shooting script comes from the introduction, which consists of an interview of Christopher Nolan by his brother (and sometimes collaborator) Jonathan. Nolan says:

I was definitely looking for a reason to impose rules in the story during the writing process. When I saw the first Matrix film, I thought it was really terrific, but I wasn’t sure I quite understood the limits on the powers of the characters who had become self-aware.

I find it odd that Nolan contrasts his film with The Matrix and thinks that he has provided a more clear explanation of how his world works than the Wachowski brothers did. The only conclusion I can come to from this is that Nolan must actually have all of the specifics of how the world of Inception works straight in his mind, but he just wasn’t able to adequately convey that clarity on the page or in the completed film. It’s interesting to me that he chooses the same influence myself and others have compared his movie to, but arrives at the completely opposite conclusion. Obviously he’s biased, and like I said, it probably all makes sense to him, but what’s weird is that he thinks The Matrix—which I consider to contain one of the best expository introductions to a fantasy world ever put to film—actually doesn’t do a good job of explaining itself.

So I don’t know that this will be the last I have to say about Inception, but I’m glad to have been able to clear up some of my own confusion, and also to solidify some of the conclusions I’d drawn from my own analysis of the film. I’ve always been a big fan of using screenplays to help gain additional understanding of a movie, especially when the movie in question was written by the director. Check out Inception: The Shooting Script if you have the same interest.

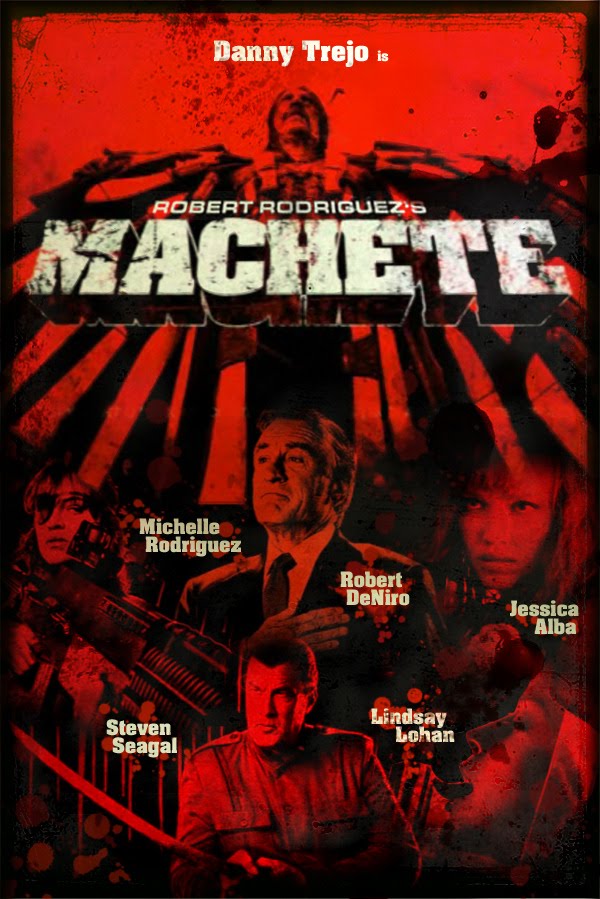

Status: In theaters (opened 9/3/10)

Directed By: Robert Rodriguez and Ethan Maniquis

Written By: Robert Rodriguez and Álvaro Rodríguez

Cinematographer: Jimmy Lindsey

Starring: Danny Trejo, Michelle Rodriguez, Jessica Alba, Jeff Fahey, Robert De Niro, Steven Seagal

In 2007’s Grindhouse, I thought that Robert Rodriguez did a better job of adhering to the gimmick with his Planet Terror than Quentin Tarantino did with his entry, Death Proof. Among those two main attractions, Grindhouse also featured several fake trailers for other would-be B-movies, and one of them, Machete, was so good that Rodriguez has now made it into an actual B-movie. Unfortunately, in expanding the seed of an idea that played so hilariously well in Grindhouse, he’s shown that he too, like Tarantino 3 years ago, hasn’t enough schlock to keep up the joke.

You come into a movie like this expecting non-stop action, over-the-top gore, and ridiculous scenarios—both in terms of the plot itself, and in the way it plays out. But Rodriguez, who co-wrote the feature-length version of Machete with his cousin Álvaro and co-directed it with his frequent editor Ethan Maniquis, seems unable to hold up his end of the bargain. Don’t get me wrong; the film has many instances of the familiar B-movie tropes you’d expect, but Rodriguez also seems to have given in to the realities of A-movie marketing, and Machete ends up attempting to straddle the line between being pure exploitative guilty-pleasure trash and having an actual story to tell. The disappointing part isn’t that the story is terribly bad, but that it only serves here to get in the way of what should have been, in my opinion, a completely vacuous movie.

In a tried-and-true set-up, Machete (Danny Trejo), a Mexican federale, sees his wife and daughter murdered by drug kingpin Torrez (Steven Seagal). Rather than going on a bloody vengeance rampage, though, Machete retreats to Texas to live as a common day laborer. Rodriguez seems to think that making a straightforward revenge flick wouldn’t be enough, and so Machete must get wrapped up in not only an underground network that helps to bring illegal aliens across the border, but also in the heated political debate over the issue. The network is headed by an innocuous-looking woman named Luz (Michelle Rodriguez—no relation to the writer-director). The Texans opposing her include a gung-ho border-vigilante cowboy (Don Johnson), an overzealous state Senator (Robert De Niro), and the Senator’s assistant (Jeff Fahey). In the middle of it all is an ambitious yet conflicted Immigration agent of Mexican descent (Jessica Alba).

Machete is reluctant to involve himself in this issue-of-the-day tale, but unfortunately for him the topicality of this movie is the one thing he’s not strong enough to overcome. Danny Trejo’s stoic expressions define the character, but the character does not define the film; instead, he ends up more often than not functioning as a bystander to the politics playing out around him. When he gets the chance to get his hands dirty, Machete realizes its more banal aspirations: the action scenes are bloody and satisfyingly ridiculous. And in true fashion, Machete always has time to shed his leather jacket when one of the many beautiful ladies surrounding him needs a little extra attention, and the gratuitous violence is sparingly matched with gratuitous nudity (it’s a pleasant surprise when Lindsay Lohan is added to this tally). The sex scenes—which, like much of the rest of the movie, I found to be disappointingly tame—also allow Rodriguez a chance to show the completeness of his talents: his band, Chingon, provides the music. While it’s repetitive in its generic porniness, it helps give Machete the levity that it’s too often missing.

The movie has its moments, no doubt, but more often than not they’re buried behind its focus on a story that just tends to get in the way. Machete moves slowly at times, which is certainly something I never expected going into it. It’s fun in its ridiculousness, when it allows itself to be ridiculous, but too often it tries to be taken seriously, to make a point. Not that it’s not a decent point to try to make, but it just doesn’t fit in this kind of movie. Planet Terror had the formula right, but with Machete some key ingredients seem to have been forgotten. We do get to see Danny Trejo on a chopper with a minigun mounted on the front, and Jessica Alba gets to deliver one of the most hilariously over-the-top rally cries ever put to film, but by the time this climax comes it feels like Rodriguez is doing it reluctantly because he knows that’s why we’re there, rather than because it’s really the movie he wants to make.

Comments Off on Grindhouse Lite

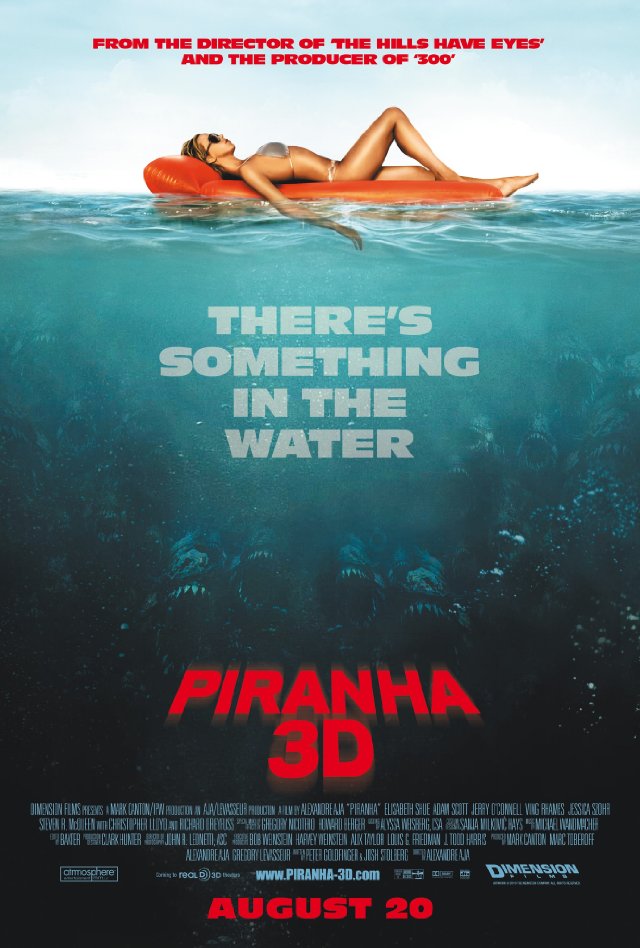

Status: In theaters (opened 8/20/10)

Directed By: Alexandre Aja

Written By: Pete Goldfinger & Josh Stolberg

Cinematographer: John R. Leonetti

Starring: Elisabeth Shue, Steven R. McQueen, Jerry O’Connell, Jessica Szohr, Kelly Brook, Riley Steele, Adam Scott, Ving Rhames

Piranha 3D is one of the funniest movies I’ve seen in a while, and if you believe me when I tell you that it’s intentionally so, you’ll take that as praise and a recommendation. It’s a gleefully vapid and exploitative horror film, relishing in all of the tropes of the genre with a tongue firmly planted in its cheek throughout.

Director Alexandre Aja knows what he’s doing. He’s clearly a fan of the original 1978 Piranha, yes, but also of Jaws, the inspiration for that film, this one, and countless others. As Spielberg did so well in 1975, Aja here gives the water a life of its own, making it a character unto itself. His cinematographer, John R. Leonetti, spends a lot of time framing shots from below, or placing the camera on the surface of the water, to give us a fish-eye’s view of the soon-to-be victims. There’s a suspense that’s built rather admirably, not so much because we’re tense and nervous about what’s going to happen, but because we’re looking forward to seeing how it does.

The script isn’t so much a rip-off of Jaws as it is a send-up, an homage. We get a small town that’s invaded annually by a large influx of tourists, but here, in true exploitation-movie fashion, it’s a spring break haven on a lake in Arizona, rather than a peaceful New England hamlet. The setting couldn’t be more perfect: Lake Victoria is over-populated with college kids looking to “go wild” (in more ways than one), and they provide a veritable douchebag buffet for the titular piranhas to feast upon.

The town is presided over by Sheriff Forester, played by my long-time love Elisabeth Shue (hey, I grew up with Adventures in Babysitting). When I first saw the trailers for Piranha 3D, I found myself wondering what the hell Elisabeth Shue was doing in this movie, but having seen it, I can give you the precise answer to that question: she’s kicking ass and taking names, that’s what. I mean, Ving Rhames, as her deputy, takes a backseat—that’s how bad-ass Lis is in this movie.

Of course, to get to that point, we have to have the semblance of a story, and what a great way to introduce an obviously ridiculous concept: Richard Dreyfuss, essentially in character as Hooper from Jaws, is the first of many victims of the prehistoric piranhas that are freed from the lake’s depths by an untimely earthquake. Aja is remarkably patient with his first act, taking the time to give us some exposition that isn’t really needed in this kind of movie except to make us impatient for the inevitable—which is to say, he builds tension by means of story, something I certainly wasn’t expecting. We meet the bad-ass female sheriff and her son, Jake (Steven R. McQueen). He’s hired by the mogul of a thinly-veiled “Girls Gone Wild” surrogate named Derrick Jones (Jerry O’Connell) to play tour guide on the lake while the “Wild Wild Girls” do their thing. Derrick has come prepared: the stars of his latest video are played by porn star Riley Steele and British model (and current Playboy cover girl) Kelly Brook. When they “go wild,” it gave me a new appreciation of the current 3D fad.

Of course, to get to that point, we have to have the semblance of a story, and what a great way to introduce an obviously ridiculous concept: Richard Dreyfuss, essentially in character as Hooper from Jaws, is the first of many victims of the prehistoric piranhas that are freed from the lake’s depths by an untimely earthquake. Aja is remarkably patient with his first act, taking the time to give us some exposition that isn’t really needed in this kind of movie except to make us impatient for the inevitable—which is to say, he builds tension by means of story, something I certainly wasn’t expecting. We meet the bad-ass female sheriff and her son, Jake (Steven R. McQueen). He’s hired by the mogul of a thinly-veiled “Girls Gone Wild” surrogate named Derrick Jones (Jerry O’Connell) to play tour guide on the lake while the “Wild Wild Girls” do their thing. Derrick has come prepared: the stars of his latest video are played by porn star Riley Steele and British model (and current Playboy cover girl) Kelly Brook. When they “go wild,” it gave me a new appreciation of the current 3D fad.

It should go without saying that Piranha 3D is a completely ridiculous movie, but what makes it so enjoyable is that it knows it. Aja has a remarkable knack for balancing the tension/startle/scare/horrify cycle that’s common in slasher-style movies like this with not only a winking knowledge that the whole thing is ludicrous, but also a reverential appreciation of his movie’s more serious predecessors. There’s a great bit where we get the piranhas’ viewpoint from below the surface of the water as they seemingly take their time selecting their victims out of hundreds of possibilities, and then we focus on a girl’s ass hanging through the center of an inner-tube; the results are predictably bloody and comedic at the same time. Or consider the film’s climax, which takes the Jaws formula and makes it its own: the heroes’ boat, firmly established as a safe harbor, springs a leak, letting the water—which we’re well-trained to identify as dangerous—in, and bringing the piranhas with it. Young Jake doesn’t have a harpoon gun, but his situation feels pretty close to that of Quint and Brody, as does his eventual solution. There are surprisingly high-brow homages like this throughout, scenes that Piranha 3D makes its own while demonstrating that it knows exactly where they come from. Of course, then on the other side of the spectrum there’s some telling breast implants that we see floating in the lake, and a dismembered, uh, member, too—I don’t think anybody would ever accuse this movie of taking itself too seriously.

Piranha 3D, as the name clearly implies, is made to be seen in 3D, and that only adds to the fun. Aside from the previously-mentioned examples of how well gratuitous female nudity lends itself to the technology, Aja also indulges in some to-be-expected instances of what I think of as the old-school kind of gimmicky 3D. Ving Rhames rips the motor off of a boat and aims it at the camera, and woah the propellers are spinning right in your face! Piranhas snap their jaws into the audience, body parts fly out of the screen, and—you get the idea. A good time is had all around.

The cast is surprisingly well-rounded, and with the exception of the child actors who play Jake’s younger siblings, it’s across-the-board capable. Jerry O’Connell in particular really breathes life into the film with his over-the-top sleaze-ball character, and Adam Scott likewise seems to be having a lot of fun playing the gentle-yet-masculine savior who comes to the rescue. I also enjoyed Jessica Szohr as Jake’s love interest-slash-damsel in distress; she provides the stereotypical nice-pretty-girl counterpoint to the impossibly hot “Wild Wild Girls.” Christopher Lloyd even turns up as a sort of mad marine biologist, and Eli Roth provides his services as an appropriately over-the-top wet t-shirt contest host. I realize it’s probably not for everybody, but Piranha 3D had me wearing a shit-eating grin for 90 minutes straight, and really, if you know that what you’re eating is mostly shit, but it tastes good nonetheless, you might as well allow yourself to enjoy it, right?

Comments Off on Fishsploitation

In my review of Christopher Nolan’s Inception, I mentioned that I find it to be a frustrating film. Among many other reasons (which I’ll get into more below), the basic source of this frustration for me is that the movie feels like it could be more than it is (and, indeed, probably should be), but also that Nolan clearly already thinks that’s the case. He makes movies that are imbued with a permeating sense of self-importance, and for me this not only holds them back, but also serves to make clear the sense of what could have been, while also adding some unneeded (and unwanted) pretension on top.

It doesn’t help that Nolan is the Internet’s darling these days, making it hard to cut through all of the hyperbole when trying to research what other people think of the movie. For instance, I went to read this review on CHUD—by a talented writer who does some of the best online movie reviews you’ll find, and for whom I have a lot of respect—but I had a hard time getting past the first sentence (I did eventually read the whole review, and it’s much more measured and well-thought-out than that first sentence initially led me to believe). I think that A.O. Scott hit it on the head when he said, “I think it used to be that ‘masterpiece’ was the last word, the end of the discussion, rather than the starting point.” But in this case, it seems, that declaration was made by many before even seeing the film in the first place.

It doesn’t help that Nolan is the Internet’s darling these days, making it hard to cut through all of the hyperbole when trying to research what other people think of the movie. For instance, I went to read this review on CHUD—by a talented writer who does some of the best online movie reviews you’ll find, and for whom I have a lot of respect—but I had a hard time getting past the first sentence (I did eventually read the whole review, and it’s much more measured and well-thought-out than that first sentence initially led me to believe). I think that A.O. Scott hit it on the head when he said, “I think it used to be that ‘masterpiece’ was the last word, the end of the discussion, rather than the starting point.” But in this case, it seems, that declaration was made by many before even seeing the film in the first place.

At any rate, there are a few issues I had with Inception—and some aspects I really appreciated—which I touched on in my review but didn’t go into in deference to my general no-spoilers rule of reviews. I’d like to take a bit of a deeper look at some of those key elements of the film here, and this time we’ll get into the details, spoilers and all.

1. Mechanics

It seems quite clear to me that Christopher Nolan is a pretty lazy and sloppy writer. He has good ideas, and they make for exciting cinema, but he’s not willing to do the work and go to the trouble of actually fleshing them all out in a totally cohesive manner. Most people seem comfortable with the mythology of Inception, and while it holds up enough to keep the movie speeding along at its non-stop breakneck pace, I think it’s pretty clear that upon a little more reflection there are some serious holes.

The film’s opening scene serves as a whirlwind introduction to the would-be science of how the dream-invasions—and the film itself—function. We learn about Extraction, the dream-stealing business in which Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio), Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), and the rest are involved.  We see Mal (Marion Cotillard) early on, and it is immediately shown (rather than explained—a rare case for Nolan) that she is an uncontrollable force in the world of dreams (though we don’t yet know the specifics). We learn how Nolan’s notion of the human mind works, specifically with regards to how secrets are stored and are able to be extracted (a clever concept that, it’s been pointed out, is anything but unique). And we’re taught, by means of explanation to Saito (Ken Watanabe), of the concept of dreams-within-dreams, which of course will become quite important about an hour from now.

We see Mal (Marion Cotillard) early on, and it is immediately shown (rather than explained—a rare case for Nolan) that she is an uncontrollable force in the world of dreams (though we don’t yet know the specifics). We learn how Nolan’s notion of the human mind works, specifically with regards to how secrets are stored and are able to be extracted (a clever concept that, it’s been pointed out, is anything but unique). And we’re taught, by means of explanation to Saito (Ken Watanabe), of the concept of dreams-within-dreams, which of course will become quite important about an hour from now.

Arthur tells Saito that this initial 2nd-level dream is his, and when things get hairy, the solution is to shoot Arthur to wake him up. And yet, when that happens, the dream continues. This is but the first in what will become an annoyingly long string of incompletely-worked-out mechanics in Inception. (It’s possible that Arthur was lying when he told Saito they were in his dream, but I’m not sure what purpose that would serve.)

When Ariadne (Ellen Page) is brought in to replace Nash (Lukas Haas) as the dream architect for the team’s upcoming mission, it’s a cheap way for Nolan to explain how everything works to the audience. Ariadne serves to ask the questions that we want answered, but the details she gets from Cobb don’t add up very cohesively. We’re told that what the team does is to insert themselves into the subconscious of the subject, which is somehow inside the dream of a third party. None of this really makes much sense, but it’s obvious that Nolan’s intention is for us to just buy Cobb’s glossing-over explanations and go along with it. The architect’s role, in particular, seems very arbitrary; we know that the architect need not be present in the dream, because later when the mission commences Ariadne has to talk her way into going along on it. We never see how the architect’s designed dreamscape gets into the dream in the first place, except we know that the dreamer can add his or her own architectural aspects if needed, because Eames (Tom Hardy) does so in his snowy fortress-assault dream (more on this in a bit).

When Ariadne (Ellen Page) is brought in to replace Nash (Lukas Haas) as the dream architect for the team’s upcoming mission, it’s a cheap way for Nolan to explain how everything works to the audience. Ariadne serves to ask the questions that we want answered, but the details she gets from Cobb don’t add up very cohesively. We’re told that what the team does is to insert themselves into the subconscious of the subject, which is somehow inside the dream of a third party. None of this really makes much sense, but it’s obvious that Nolan’s intention is for us to just buy Cobb’s glossing-over explanations and go along with it. The architect’s role, in particular, seems very arbitrary; we know that the architect need not be present in the dream, because later when the mission commences Ariadne has to talk her way into going along on it. We never see how the architect’s designed dreamscape gets into the dream in the first place, except we know that the dreamer can add his or her own architectural aspects if needed, because Eames (Tom Hardy) does so in his snowy fortress-assault dream (more on this in a bit).

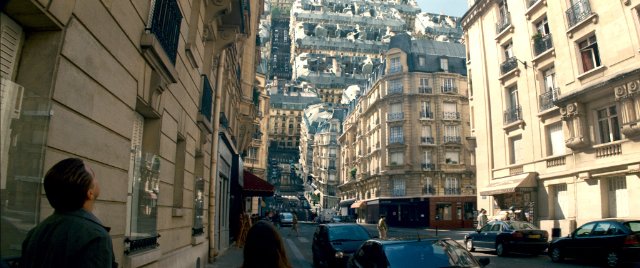

What’s most disappointing about the learning/mechanics sequence, though, is that we are shown some awesome effects that can be achieved—the exploding cafe, the folding streets, the mirrored corridor, the Penrose stairs—but rather than being a setup for even more awesome tricks to come later, these exist in the film purely for the visual thrill they provide as a way to spice up an otherwise drawn-out expository sequence. The only one of these tricks that comes up at all in the rest of the film is the Escher-like staircase effect, which Arthur uses to evade a bad guy in the hotel dream. And this further begs the question of how this all works: did Ariadne put those stairs in the hotel, for Arthur to make use of if needed, or was he able to call upon them only when the situation arose? (After the bad guy Arthur is trying to get away from falls down the stairwell, he mumbles something that was unintelligible to me in two viewings, but for all I know it might be along the lines of “Thanks, Ariadne.”)

What’s most disappointing about the learning/mechanics sequence, though, is that we are shown some awesome effects that can be achieved—the exploding cafe, the folding streets, the mirrored corridor, the Penrose stairs—but rather than being a setup for even more awesome tricks to come later, these exist in the film purely for the visual thrill they provide as a way to spice up an otherwise drawn-out expository sequence. The only one of these tricks that comes up at all in the rest of the film is the Escher-like staircase effect, which Arthur uses to evade a bad guy in the hotel dream. And this further begs the question of how this all works: did Ariadne put those stairs in the hotel, for Arthur to make use of if needed, or was he able to call upon them only when the situation arose? (After the bad guy Arthur is trying to get away from falls down the stairwell, he mumbles something that was unintelligible to me in two viewings, but for all I know it might be along the lines of “Thanks, Ariadne.”)  At any rate, whether the architect has put these stairs in place ahead of time or whether the dreamer can summon the effect at will, neither situation really clarifies what’s going on—if Arthur is able to control the environment of his own dream in such ways, what’s the need of the architect in the first place?

At any rate, whether the architect has put these stairs in place ahead of time or whether the dreamer can summon the effect at will, neither situation really clarifies what’s going on—if Arthur is able to control the environment of his own dream in such ways, what’s the need of the architect in the first place?

My point here is not just to point out how incompletely explained the mechanics of the film are; my point is that I feel pretty confidently that Christopher Nolan himself has not worked out these details. His film is comprised of half-developed concepts that make for exciting and “complex” cinema, but they’re not fleshed out to an extent that holds up to the kind of scrutiny a film like this almost demands. (It’s worth noting that the marketing scheme for Inception has now gone into “You need to see it more than once!” territory.) I realize that I am bothered by such things more than most, but to me a good film—especially one that is going to be deemed “a masterpiece”—needs to have this level of cohesion; it needs an air-tight script, and that is simply not the case here.

2. Characters

One of the biggest tell-tale signs of lazy writing is the fact that in an ensemble cast, there are precisely two characters with any kind of backstory or actually developed characterization whatsoever. They are Fischer (Cillian Murphy, who gives a really great performance, particularly at the film’s climax), and Cobb, whose story it is that we’ve ostensibly come to watch. The rest of the characters exist not to be representations of people, with real emotions and problems and goals, but simply to fill roles, to be types. I’ve already mentioned Ariadne, whose purpose in the movie is twofold: she asks Cobb for the explanations that we as an audience require in order to be able to follow along, and she reminds Cobb (and us)—repeatedly—of the function of Mal.  It seems to me that about 50% of her dialogue is some variation of the line, “Cobb, you can’t control Mal and we don’t know what she’ll do! She’s dangerous!” I find Ellen Page’s performance to be exceptionally dull, too; she sticks out like a sore thumb in what is otherwise a pretty solid cast as the one person who’s not putting their heart and soul into it. This is likely at least partially a result of her character’s function: she’s not really much of a character at all, she’s just there because Nolan thinks we’re all drooling, popcorn-inhaling idiots who wouldn’t be able to keep things straight without her. (And who the hell is named Ariadne, anyway? I know it’s a reference to a labyrinth-foiler from Greek mythology, but who actually gives their kid that name? It’s like Nolan just Googled some shit about labyrinths while writing the script and used the first thing he found.)

It seems to me that about 50% of her dialogue is some variation of the line, “Cobb, you can’t control Mal and we don’t know what she’ll do! She’s dangerous!” I find Ellen Page’s performance to be exceptionally dull, too; she sticks out like a sore thumb in what is otherwise a pretty solid cast as the one person who’s not putting their heart and soul into it. This is likely at least partially a result of her character’s function: she’s not really much of a character at all, she’s just there because Nolan thinks we’re all drooling, popcorn-inhaling idiots who wouldn’t be able to keep things straight without her. (And who the hell is named Ariadne, anyway? I know it’s a reference to a labyrinth-foiler from Greek mythology, but who actually gives their kid that name? It’s like Nolan just Googled some shit about labyrinths while writing the script and used the first thing he found.)

Everybody else in the cast is exclusively one-dimensional. There’s been a lot written about Inception as a metaphor for film production itself (probably the best of these that I’ve read is this one—by the same writer, Devin Faraci, who wrote the review I referenced earlier). But no matter how you look at the roles of the supporting cast, you’re not going to find much depth there. The team-building sequence in the movie is familiar from any heist flick, except that Nolan doesn’t bother telling you much of anything about who these people are; they exist to fill a role, and that’s it.  Of the supporting cast members of the dream team, I think that Tom Hardy stands out as Eames; he’s the benefactor of the movie’s lone attempts at humor. Joseph Gordon-Levitt tries too hard to be a badass as Arthur (his forced-deep voice makes it impossible for me to take his character very seriously), and poor Dileep Rao seems like he’ll spend his whole career being cast as a mystical-Eastern-guy stereotype (his Yusuf is not very unlike the character he played in Drag Me to Hell, with a little of his Avatar scientist blended in).

Of the supporting cast members of the dream team, I think that Tom Hardy stands out as Eames; he’s the benefactor of the movie’s lone attempts at humor. Joseph Gordon-Levitt tries too hard to be a badass as Arthur (his forced-deep voice makes it impossible for me to take his character very seriously), and poor Dileep Rao seems like he’ll spend his whole career being cast as a mystical-Eastern-guy stereotype (his Yusuf is not very unlike the character he played in Drag Me to Hell, with a little of his Avatar scientist blended in).

Compounding the confusion of the film—or at least adding to the amount of effort that’s required to follow it—is the inconsistent pronunciation of some of these characters’ names. Sometimes Yusuf is YOO-sef, sometimes he’s yeh-SOOF. (Arthur refers to him using the latter pronunciation at a key point in the hotel dream, and I didn’t catch what he was referring to until my second time seeing the film.) There is only one instance where I’ll excuse a movie for such sloppiness, and that’s in the Star Wars movies, where Lando pronounces “Han” and “Leia” differently than everybody else. But that’s excusable because it’s Billy Dee Williams, and who’s going to correct Billy Dee Williams?

3. Video Games

Another frequent commentary on Inception is that it feels, and plays out, like a video game movie that just so happens to not actually be based on a video game. This is usually presented as a positive, but I’m not sure why. To me, it’s a “video game movie” because it’s structured in terms of “levels,” with each getting progressively more difficult for the heroes to navigate. These levels are populated by unnamed, usually faceless foot soldiers, who are easily dispatched and only serve to slow down the progression to the level’s ultimate goal—and to keep the film dense with action scenes. There’s a good visual representation of how the levels stack here, but the one thing I’d add is that each level even features a “boss,” a character that is harder to get past than the other sentries have been, and who guards the level’s final objective.

- In level 2 (the Van Chase), after plowing through bad guys with relative ease, Yusuf must fight through a Big Black SUV that gives him more trouble on the bridge. This SUV is his last obstacle before being able to drive through the guardrail and into the water.

- In level 3 (the Hotel), there is one guard who gives Arthur more trouble than the rest. He is finally able to evade this guard by using the Penrose steps trick in a stairwell.

In level 4 (the Snow Fortress—the most video game-like part of the film), the final boss is Mal, who shows up just before the goal has seemingly been reached. Cobb must shoot her to clear the way for Fischer to enter the vault and confront his father.

In level 4 (the Snow Fortress—the most video game-like part of the film), the final boss is Mal, who shows up just before the goal has seemingly been reached. Cobb must shoot her to clear the way for Fischer to enter the vault and confront his father.- In level 5 (Limbo), things become sort of a clusterfuck. The “boss” here is again Mal, who seems to have more power this time around—a common video game trope.

The most insightful piece I’ve read about Inception-as-video-game is Inception‘s Usability Problem, which explores the film’s exposition as a tutorial in how to watch it. I particularly enjoyed the comparison that article makes to The Matrix, an obvious inspiration for this film that serves as a telling example of how such things are handled by far better screenwriters than Nolan.

4. Performing Inception

Inception goes to great lengths to ensure that we understand the importance of the “kicks” that serve to wake the characters from the various levels of dreams. The 4-way kick sequence, from the time Yusuf drives the van off the bridge, to the time it hits the water, and everybody awakens from the multiple levels of dreams simultaneously, occupies a full 30 minutes of screen time. It’s a virtuoso example of cross-cutting and sustained tension. (Most impressive may be the fact that although the ever-falling van evokes the old cliche of a slowly-closing overhead door that seems to backtrack a bit every time we cut to it, Nolan never falls into this suspension of disbelief-killing trap.)

As the film races towards its climax, however, Nolan throws his own rules by the wayside. In the snow fortress level, when time becomes of the essence, a shortcut appears out of nowhere to save the day. (“Did Eames add any shortcuts?” Cobb asks Ariadne. Why, how fortunate, it just so happens that he did!) Nolan seems to have a knack for writing himself into a corner, and then pulling something out of his ass to gloss over the would-be problem and keep the action barreling forward. The worst such instance is the business with the kicks; towards the end of the half-hour-long, synchronized 4-way kick sequence, we find Cobb and Saito still down in Limbo. We know that this is a tenuous situation because Nolan has gone out of his way to warn us, over and over, about how people can get stuck “down there.” And yet, how do Cobb and Saito come out of it? It’s not shown, but we can infer that they simply shoot themselves (the last image in Limbo we see is old-Saito reaching for a gun).

As the film races towards its climax, however, Nolan throws his own rules by the wayside. In the snow fortress level, when time becomes of the essence, a shortcut appears out of nowhere to save the day. (“Did Eames add any shortcuts?” Cobb asks Ariadne. Why, how fortunate, it just so happens that he did!) Nolan seems to have a knack for writing himself into a corner, and then pulling something out of his ass to gloss over the would-be problem and keep the action barreling forward. The worst such instance is the business with the kicks; towards the end of the half-hour-long, synchronized 4-way kick sequence, we find Cobb and Saito still down in Limbo. We know that this is a tenuous situation because Nolan has gone out of his way to warn us, over and over, about how people can get stuck “down there.” And yet, how do Cobb and Saito come out of it? It’s not shown, but we can infer that they simply shoot themselves (the last image in Limbo we see is old-Saito reaching for a gun).  And then, we realize, come to think of it, that’s how Cobb and Mal escaped Limbo earlier, too, isn’t it? They were down there for “something like 50 years,” fearful that if they ever escaped it would be without their minds intact, and yet all it took was laying on some train tracks to wake them up.

And then, we realize, come to think of it, that’s how Cobb and Mal escaped Limbo earlier, too, isn’t it? They were down there for “something like 50 years,” fearful that if they ever escaped it would be without their minds intact, and yet all it took was laying on some train tracks to wake them up.

So while the other characters all had to jump through hoops (and, literally, perform acrobatics) to pop themselves one level at a time from limbo to the snow fortress to the hotel to the van and finally back to reality aboard the plane, Cobb and Saito are able to just skip all of that shit and wake up directly from limbo. This is convenient, because Nolan doesn’t want to lose his momentum; at this point in the movie what he’s interested in is getting you to his ambiguous ending, where you won’t find a payoff per se, but rather the food for thought that Nolan desperately wants you to emerge from the theater discussing. And again I contend that the reasons why this whole kicking thing, and the details of how Limbo works, don’t really make any sense is because Nolan himself doesn’t really understand them, either. He’s just throwing some trippy shit at you, admittedly in the name of keeping his movie exciting, but he doesn’t want to put in the effort to actually work it all out.

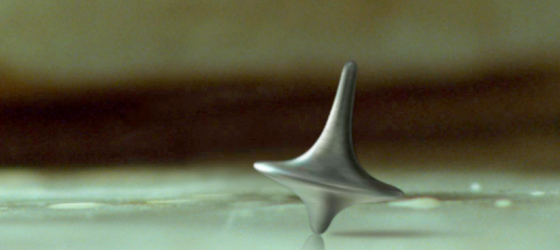

The much-discussed top is what Nolan is driving towards, the reason he glosses over all of these details once Fischer has had his therapeutic moment and the mission of performing Inception has been successful. Because what Nolan has done is exactly what his characters at this point have done: he’s performed Inception on you, the audience, of the same idea that Cobb was able to implant into his wife’s mind. He’s made you doubt “reality”—the reality of the film—and that is the concept he wants to leave you with. Don’t ignore the significance of the fact that Leonardo DiCaprio looks almost exactly like Christopher Nolan in this movie; he’s the director’s representation of himself onscreen, and it’s no coincidence that the director’s primary aim with his film is the same as the main character’s aim in his story.

I think that what’s important about the film’s final image isn’t whether the top stops spinning, it’s the fact that Cobb no longer cares whether it does or not. He’s made his decision, that “this”—wherever “this” may be—is what he wants to know as Reality from now on. Whether he’s still dreaming is irrelevant; this is now his reality. He’s made a decision similar to the one that Joe Pantaliano’s character makes in The Matrix: I don’t really care anymore if this is real or not, I just know that this is what I want to believe as my own reality. The steak tastes too good to decide otherwise; the joy of seeing his children’s faces is too much to write off as not being “real.” (The concept here isn’t as complicated as many have made it out to be; it’s actually explicitly stated earlier in the film—catharsis is catharsis, regardless of whether it occurs in a dream or in one’s waking life.)

As underwritten as I find most of Inception to be, this to me is its biggest redeeming factor. After half-assing a lot of its concepts for most of its duration, in the film’s final minutes Nolan finally solidifies something of a theme, and it’s one that is worthwhile. The idea of subjective reality is one that’s fun and intriguing to explore (Nolan has done so many times before, most notably in Memento), and one that can perpetually be revisited (“Make sure you see it at least twice!”). Coming on the heels of—and tying into—the resolution of Nolan’s other theme, fatherhood, it makes for a finally-satisfying experience.

And yet, there’s still something missing here. The thesis of the film falls a little flat for me, I think due to the fact that it has gone to such lengths to reach this point, and it’s done somewhat of a sloppy job of it in the process. This doesn’t mean that I write the entire thing off, and it certainly doesn’t mean that I think you’re dumb if it does fully work for you. It’s just that it doesn’t quite resonate with me as much as I think it should, and that leaves me with an overall disappointing impression of the film. As I said in my review, Inception is a movie I enjoy—with so much action and mind-bending effects, it’s hard not to have a good time watching it—but I think it could’ve been a movie I really loved.

— —

To give credit where it’s due, most of the links above I found via Jim Emerson’s excellent Scanners blog. Jim’s done a great job collecting, excerpting, and commenting on a lot of the better writings there’ve been related to Inception. While he’s a bit harder on the movie than I am, as he says (and I totally agree), “you don’t have to particularly like a movie in order to find it worthy of analysis and discussion.” And luckily, I do like this movie; it’s the distinction between the reasons why that’s the case and those for why I don’t completely love it that make it so worthy of that analysis and discussion to me in the first place.

Status: In theaters (opened 6/25/10)

Directed By: Dennis Dugan

Written By: Adam Sandler & Fred Wolf

Cinematographer: Theo van de Sande

Starring: Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, Rob Schneider, Salma Hayek

As is probably obvious from the content on this site, I see a fair amount of movies. My wife and I see so many, in fact, that it is apparently possible for us to go through withdrawal. And so it came to pass that on a recent vacation, about 13 days into it, finding ourselves with the first free afternoon of the trip, we decided we’d go see a movie. This had a few benefits: as we were in Illinois in July, it was incredibly hot and humid out, and so the theater would give us a nice excuse to sit in the air conditioning for a couple of hours during the most unbearable part of the day. We could also get popcorn for lunch, which is one of our favorite things to do—and before you’re tempted to let me know about the calorie or fat or whatever other content of such a meal, I’m aware, and it’s actually not that bad: even a huge tub of popcorn at a movie theater with butter drizzled all over it is like 1300 calories, and split 2 ways that’s really not that bad of a lunch. But I digress. It also seemed like a nice idea because, as much as we love our family and friends, spending the previous 2 weeks driving all over the Midwest to visit as many of them as possible was exhausting, so having a little time to ourselves in the peace and quiet of a dark theater was about as inviting an escape as I could imagine.

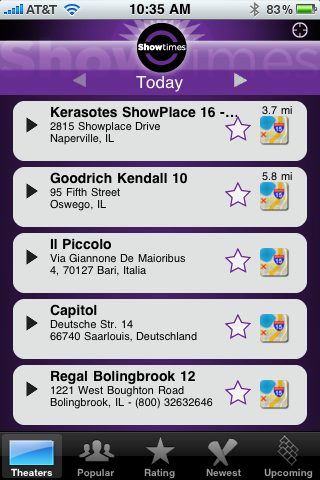

The one thing we didn’t consider, unfortunately, was that there wasn’t shit playing. Our options were basically to sit in a theater full of children seeing an animated flick (Toy Story 3 or Despicable Me), or to try to convince the other to succumb to our respective guilty pleasures: mine for 1980s nostalgia (Predators), hers for bad comedies (Grown Ups). And marriage being what it is, we “agreed” on the latter, and this is all really my extremely roundabout way of trying to explain to you, and myself, how in the hell I ended up sitting there watching this movie in the first place.  There is one side-story here that’s sort of worth telling, too: a bug in my iPhone’s Showtimes app led to an amusing listing of “nearby” theaters from where I sat in my parents’ house in Plainfield, Illinois (at right; click to enlarge).

There is one side-story here that’s sort of worth telling, too: a bug in my iPhone’s Showtimes app led to an amusing listing of “nearby” theaters from where I sat in my parents’ house in Plainfield, Illinois (at right; click to enlarge).

And honestly, that single image brought me more chuckles than did the entire experience of sitting through Grown Ups. It’s one of those movies where it’s impossible for me to even picture the writers sitting together and thinking that what they’ve put on the page is actually humorous, much less expecting an audience of people to laugh at the finished product that will come from it. And yet, laugh they did: the half a dozen other people who went to the Showplace 16 in Naperville for that Thursday noontime showing were absolutely laughing their asses off. I’m just out of touch with middle America, I guess. These are, presumably, the same people who flocked to see Paul Blart: Mall Cop a year and a half ago. They’re people I feel pretty confident saying I have nothing in common with.

So this whole post has been—as I’m sure is sort of clear by now—an excuse to convince myself that I’ve lived up to my goal of writing about every movie I see in the theaters, and yet not actually having to write about the movie Grown Ups, which I didn’t really want to see and kind of wish I hadn’t. It’s basically a retarded version of The Big Chill; its biggest attempts at laughs come from Kevin James falling out of a pool, or falling into a lake, or pissing on himself, or otherwise just being fat and stupid. Oh, and there’s also this brilliant gag having to do with Rob Schneider’s daughters: two are hot, and one has a mullet. Get it?

What I really don’t understand here, though, is Adam Sandler. The guy has shown in recent years that he can actually act (Reign Over Me) and that he can be actually funny while actually acting, too (Funny People). And yet he keeps coming back to what I suppose should be considered his bread and butter, these mindless, unfunny, surprisingly crowd-pleasing phoning-it-in movies. More power to him, I guess. Next time I think I’ll just push harder for Predators.

Status: In theaters (opened 7/16/10)

Directed By: Christopher Nolan

Written By: Christopher Nolan

Cinematographer: Wally Pfister

Starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Ellen Page, Tom Hardy, Ken Watanabe, Cillian Murphy, Marion Cotillard

I honestly can’t decide if I should fault Christopher Nolan for helping to dumb down film as we know it, or give him credit for capitalizing on the already-existing phenomenon. I think the answer is probably both: he’s a guy who’s recognized the fact that movies don’t need to make sense to be considered “smart” anymore, that hand-waving can take the place of legitimate plotlines, that repetitive sophomoric “explanations” can get an audience to go along with whatever nonsense you present them with, and yet he also knows how to present an entertaining spectacle, to throw excitement on the screen in spades and just hope you don’t try to make sense of it while enjoying the ride. Inception is probably the most direct example of what I’m pretty sure will become Nolan’s trademark style from this point on: it’s a big, fun adventure that moves fast and asks you not to question where it’s going, except for when it takes the time to explain the parts that don’t matter. For instance: the plot revolves around a guy named Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his team of dream-snatchers, except that what they deal with aren’t really like dreams at all. Consider a scene that I’m sure you’re familiar with if you’ve seen the film’s theatrical trailer (see the 0:40 point)—or the poster above—where the streets of Paris fold over onto each other, demonstrating the control over the dream world that these experts have. Does this have anything to do with the movie whatsoever? Of course not; it’s an excuse to show off an eye-popping effect (and it does, admittedly, look amazing), but one that has no relevance or consequence to the film’s story. This one small example, as far as I’m concerned, pretty much tells the whole story of how Christopher Nolan makes movies, and Inception is one long, loud, and in-your-face treatise on what a summer blockbuster in 2010 is going to be.

The formula should be recognizable from Nolan’s The Dark Knight: there’s some amateur psychology loosely stringing everything together, here explained by way of audience surrogate Ellen Page, with help from Joseph Gordon-Levitt (doing his best bad-Keanu Reeves impression), who are charged with delivering the kind of embarrassing dialogue I found so distasteful in the Batman movie—it’s of the form, “Here is what must happen, otherwise this will happen, which would be bad,” and it’s repeated multiple times just to make sure that you didn’t miss it, because at the end of the day, I’m pretty sure Nolan’s view of you, his audience, is that you’re a complete idiot and can’t follow the most simplistic plot developments, even when their ramifications are explained to you every 20 minutes or so. And then on the other hand, he expects you to not question the major aspects of his story: how does this whole dream-stealing thing work in the first place? The description that’s given is about as useful as Norville Barnes’s explanation of his brilliant idea to the heads of Hudsucker Industries—”You know,” you can virtually hear DiCaprio saying, “for dreams!”

The central conflict—and would-be moral—of the film is basically more psychobabble nonsense, but I don’t want to delve into it too much here because it’d fall into the realm of spoilers. Let me just say that I absolutely love Marion Cotillard, and think that she’s as beautifully mesmerizing here as she’s been in everything else I’ve seen her do, and yet her role in Inception feels like little more than an excuse for the script to attempt to screw with your head. Hell, that’s basically all the whole movie is, come to think of it: Nolan is going for a roller-coaster ride of a mindfuck, and anything that helps him achieve that end gets thrown in whether it really fits or makes sense or not.

Structurally, things are pretty strange, too: we get the Return of the Jedi style of setting up several simultaneous action sequences that are intercut with each other, to all be resolved at roughly the same time, except here there’s an additional twist: each thread of the action is actually a different layer of dream, because in the world of Inception it’s possible to induce dreams-within-dreams (with the to-be-expected laborious explanations of how this works, and what its arbitrary limitations are). What Nolan basically ends up with is an hour-long exposition, then an hour-plus action setpiece, and then an abbreviated concluding scene that aims to leave the viewer with some open-ended questions that are inconsequential anyway. While the action is happening, though, it’s something to behold. Things happen at a fast and furious pace, and the action, like the plot itself, is best enjoyed if you just let it overtake you instead of trying to make sense of it all as it goes. Wally Pfister shoots the film like he did The Dark Knight, which is to say with a sense of scope that’s uniquely fitting and awesome. And Hans Zimmer seems to have put in overtime, his score maintaining a throbbing build for a good 45-minute stretch towards the film’s climax, which is quite a feat in itself.

I realize a lot of the above may sound like a lot of bitching over a movie that’s really not as bad as I might be making it sound. In fact, I think I like it quite a bit—I just find it to be extremely frustrating. Inception has some good ideas, is creatively very unique, features amazing practical effects that suck you into its world, and takes you on a mind-bending ride that’s quite enjoyable if you’re able to just sit back and allow your mind to be bent, rather than expecting it to be used for other purposes. As far as this type of movie goes, I’ll take the Nolan version over the extremely disappointing attempt at a brain-twister Scorsese brought us earlier this year with that other DiCaprio vehicle, Shutter Island. And I don’t think it’s any question that Inception has a lot more to offer than a mindless effects-fest like Avatar. My main issue is that, like most of Nolan’s other films, Inception feels like a) it could be so much more, and b) it thinks it already is.

Status: In theaters (opened 6/23/10)

Directed By: James Mangold

Written By: Patrick O’Neill

Cinematographer: Phedon Papamichael

Starring: Tom Cruise, Cameron Diaz

I’ve realized that I’m more or less a sucker for this type of movie: big-budget, well-written, highly polished, international/globe-trotting/political intrigue/espionage stories, with big-name stars, helmed by an accomplished director. Knight and Day is but the newest in this line, and while it’s definitely not extremely original and/or unique among this type of film, it certainly satisfies for what it is.

What surprises me most about this movie is that I’ve never really considered myself to be a big fan of either of its stars, but I found myself liking them both quite a bit here. Tom Cruise plays an extremely likable government agent named Roy Miller, who goes out of his way to protect the innocent June Havens (Cameron Diaz) when she gets mixed up in his operation. Even when the script attempts to introduce doubt as to Roy’s intentions, though, it’s so obvious that he’s exactly who he says he is—the good guy—that this is one attempt at a twist that’s unsuccessful. June, likewise, is a character who’s almost impossible not to root for. Diaz plays her as a genuinely friendly person, not the naive, bumbling girlie-girl I’d assumed I’d encounter. She’s willing to get her hands dirty, and that only adds to the fun.

The plot is basically what you’d expect, beginning with a mix-up that leads to Roy and June getting stuck with each other for a while. It twists and turns and surprises as it should, though without any crazy, hard-to-swallow reversals. The one thing that annoyed me was how Knight and Day seems to ignore the realities of time. It’s hard to know how many days have passed at a couple of points in the film, and this wouldn’t seem like a big issue if they hadn’t previously mentioned specific deadlines that had to be met. It’s one of those things that’s sort of glossed over, though, and obviously we’re not supposed to worry about such things; when you’re being whisked around from place to place, action sequence to action sequence, you’re just supposed to enjoy the ride.

The most recent film that operated in much the same way was The International, one that I enjoyed equally as much as this one. There’re also shades of The Saint thrown in here, with Paul Dano (from There Will Be Blood) factoring in as a wunderkind of sorts who alternately provides and functions as the always-needed MacGuffin. There’s some influence from North by Northwest here, too, as so many of these types of films exhibit.

Director James Mangold already has several interesting films under his belt, most recently Walk the Line (which he also co-wrote) and 2007’s excellent 3:10 to Yuma, and Knight and Day shows the same level of polish as those productions. It’s another interesting addition to an already-varied resume that will be exciting to watch continue to develop. I don’t have a ton to say about this one, other than it is what it is, and sometimes that’s exactly what you’re looking for. Just don’t expect some profound explanation for the title, because that’s the one aspect of this movie that seems to have been completely half-assed. Particularly amongst the other movies that’ve been coming out this summer, though, it doesn’t exactly have to hit it out of the park in order to satisfy.

Comments Off on Big Fun Action