To wrap up my rundown of Inglourious Basterds, the Fugue—maybe I should’ve called it The Well-Tempered Basterd—I wanted to take a step back and try to look at the overall structure as it exists over the course of all 5 chapters of the film. It’s only fitting that I make this a 5-part series, after all.

Quentin Tarantino has always had a reputation of being a great screenwriter, mostly because of his skills with dialogue. He’s also got a reputation as a director who loves to play with his films’ chronologies, particularly with his earlier movies (Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, but also his screenplays for True Romance and Natural Born Killers), though he had his way with the timeline of Kill Bill as well. Inglourious Basterds, to my thinking, represents a new achievement for him in story structure, seeing him effortlessly balance several characters, all of equal importance to his narrative, while playing them off of each other in virtually every combination, the four “voices” of the “fugue” that I’ve been describing chief among them.

I should mention that I did this from memory, after seeing the film twice in the theater on its opening weekend, so it wouldn’t surprise me to learn that I’ve got a few events out of their proper order. (I found a draft of the script online to try to check myself against, but it’s different enough from the final film as assembled that it wasn’t much help.)

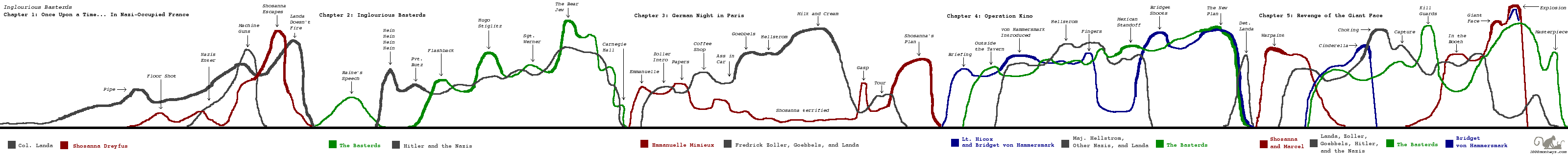

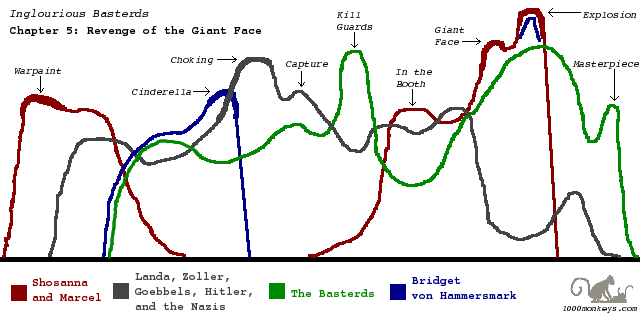

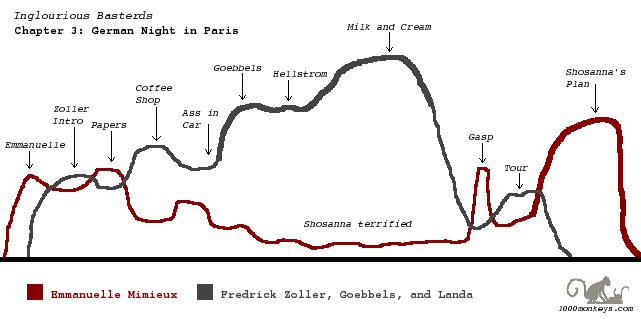

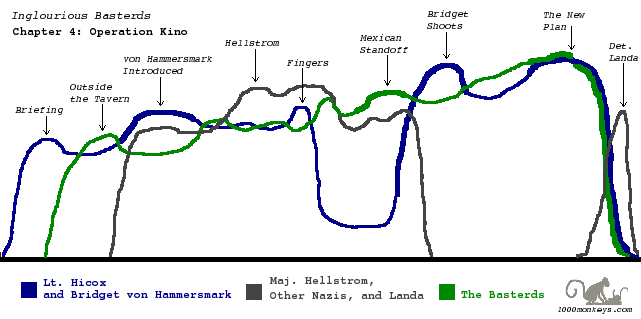

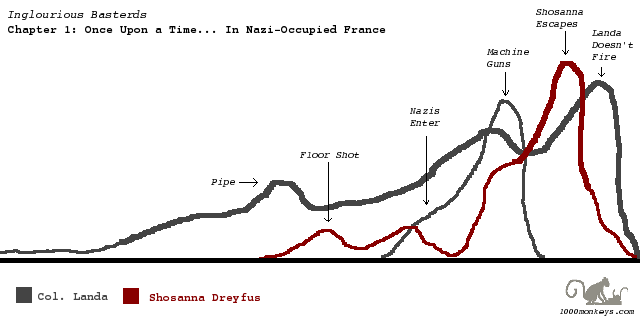

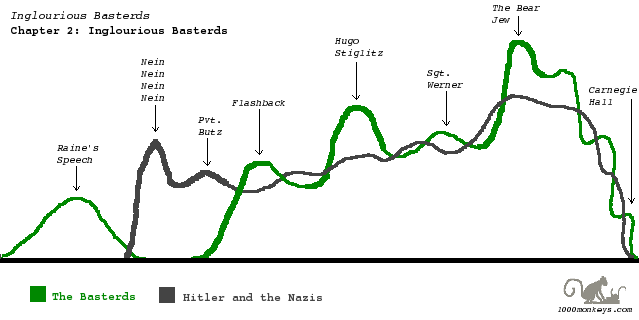

The character timelines I’ve included with each chapter are representative of how I tend to picture character arcs in my mind when thinking about a screenplay’s structure. It’s worth pointing out that they were normalized so that the peak of each chapter appeared as the maximum “amplitude” of the character or characters, resulting in a fairly interesting pattern when they’re all looked at together, but one that doesn’t quite capture the real progression over the course of the entire film.

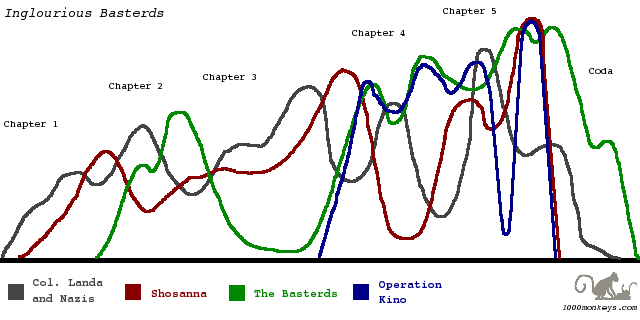

For instance, while the Bear Jew‘s emphatic flourish in Chapter 2 is the emotional and structural peak of that movement, it’s certainly not nearly as large a moment as when the cinema burns and explodes in Chapter 5, as the graph above appears to be indicating. A more accurate overall representation would look more like this:

Now it really looks like a fugue. (I think so, at least…)

I’m hoping to do some more of this type of in-depth analysis in the future, though future such endeavors will probably be without the use of an overextended metaphor—but you never know.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Epilogue

Previously, we’ve looked at the first four chapters of Inglourious Basterds in the context of viewing it as a quadruple fugue. Now we come to the final chapter, where all four voices are present, and each achieves its resolution in what corresponds to Act III. Refer to the intro to “The Inglourious Fugue” for definitions of the terms I’m using and of the primary voices being examined.

Chapter 5: Revenge of the Giant Face

It’s the night of the premiere of Nation’s Pride, Goebbels‘s newest propaganda film, starring its subject, Fredrick Zoller. In the preceding two chapters, we learned of two separate plots to kill the Nazis who have assembled at the cinema: Shosanna and Marcel intend to burn it down with all of the Nazis inside, while Bridget von Hammersmark and the Basterds intend to blow it up.

Chapter 5 opens with Shosanna getting ready for the big night in a scene where Tarantino allows himself to indulge several of his favorite fetishes. As the beautiful French blond applies her makeup as if it were warpaint, re-establishing her voice in this chapter, “Putting Out Fire” blares over the soundtrack. (Not only does Tarantino use a song that was written 40 years after when his film takes place, but he uses the theme from a different movie, too. Pure balls… and it works.) Wearing her red dress, Shosanna dons a black veil and goes to survey her cinema, which the Nazis have liberally decorated. The red and black of her outfit makes her fit right in with their tapestries and posters that litter her lobby, and it also solidifies her as an extension of her cinema. She’s a captain prepared to go down with her ship.

Looking down over the cinema‘s lobby from the 2nd-floor balcony, Shosanna sees the arrival of most of the Third Reich high command: Goebbels, Goring, Boorman (with Hitler on his way). Then the Basterds, loosely disguised as Italian filmmakers, and Bridget von Hammersmark, her foot in a high-heeled cast, make their entrance. This is the first time in the piece when all four primary voices are present simultaneously, and the tension hangs thick in the air.

Col. Landa spots the scheming members of Operation Kino and approaches them in the lobby, once again asserting his voice above the din. After a comedic high point involving contrasting skills with the Italian language, two of the Basterds take their seats in the theater, elevating the dissonance of their voice in this chapter by moving their plan one more step forward. Landa takes von Hammersmark into the office, where we get another tense sit-down scene.  This one doesn’t last very long, though; as soon as the Cinderella moment—QT has a major foot fetish—confirms Landa‘s suspicions (justifying his belief in his own detective skills), he pounces on von Hammersmark with a motion that calls back to his strudel-stabbing in Chapter 3, silencing her voice for good and giving us our most intense look at just what Landa is capable of. This is the first time we’ve seen him involved in an act of violence since Chapter 1, and the first (and only) time it’s been Landa himself who did the killing.

This one doesn’t last very long, though; as soon as the Cinderella moment—QT has a major foot fetish—confirms Landa‘s suspicions (justifying his belief in his own detective skills), he pounces on von Hammersmark with a motion that calls back to his strudel-stabbing in Chapter 3, silencing her voice for good and giving us our most intense look at just what Landa is capable of. This is the first time we’ve seen him involved in an act of violence since Chapter 1, and the first (and only) time it’s been Landa himself who did the killing.

Riding an adrenaline high, the voice of his subject peaking, Landa orders his men to apprehend Lt. Raine, who is taken, along with Pfc. Utivich, to a tavern where the Germans have set up a base of communications.  Here the voice of Landa shifts its pitch, revealing that he is willing to allow the Basterds to go through with their plan, so long as he’s remembered by history as the hero behind it all. This is a different tone than the one we’ve become used to hearing from Landa, as exemplified by his contrasting attitudes towards his nickname (“The Jew Hunter“) between Chapter 1 and now. It’s also another instance of Landa demonstrating his prowess as a detective, a sub-theme of his subject that has surfaced a few times now, but never more forcibly than here. Revealing himself to not be as committed to the Nazi doctrine as he might’ve previously appeared, Landa sides with the cause of the Basterds to “end the war tonight,” and we see a brief flashback disclosing the fact that he planted Raine‘s bomb in the opera box where Hitler and Goebbels are seated.

Here the voice of Landa shifts its pitch, revealing that he is willing to allow the Basterds to go through with their plan, so long as he’s remembered by history as the hero behind it all. This is a different tone than the one we’ve become used to hearing from Landa, as exemplified by his contrasting attitudes towards his nickname (“The Jew Hunter“) between Chapter 1 and now. It’s also another instance of Landa demonstrating his prowess as a detective, a sub-theme of his subject that has surfaced a few times now, but never more forcibly than here. Revealing himself to not be as committed to the Nazi doctrine as he might’ve previously appeared, Landa sides with the cause of the Basterds to “end the war tonight,” and we see a brief flashback disclosing the fact that he planted Raine‘s bomb in the opera box where Hitler and Goebbels are seated.

From here it’s a frantic race to the climax. Back at the cinema, Sgt. Donowitz and Pfc. Ulmer spring into action. While they’re preparing their assault on the Hitler/Goebbels opera box, Zoller excuses himself to make another attempt at winning Shosanna‘s affections. He finds her alone in the projection booth, Marcel having already left to lock the doors to the theater and take his place behind the screen. In the booth, Shosanna and Zoller both meet their end in true spaghetti Western tragic fashion, but not before Shosanna has had a chance to switch to her “special” fourth reel.

Immediately after her death, Shosanna‘s voice reaches its apex, as she appears as a giant face on the screen, tormenting the theater full of Nazis with the information that they are all about to die. Marcel‘s voice gets its last flourish as he flicks his cigarette onto the stack of nitrate films, igniting the screen, with the rest of the cinema to follow. At the same time, the Basterds burst into the opera box and proceed to machine-gun the ever-loving shit out of Hitler and Goebbels, before turning their fire onto the crowd below, mirroring the actions of Zoller in Nation’s Pride shown only moments before. They also take the time to riddle the corpses of Hitler and Goebbels on the ground with more bullets, achieving a bookend effect with the slaughter of Shosanna‘s family under the floorboards in Chapter 1.

Amidst the chaos, the face of Shosanna is still visible in the smoke and flames that have taken the place of the screen, cackling as the theater full of Nazis scramble for their lives. The bombs of Operation Kino then go off, as the Kino voice peaks along with Shosanna‘s in victory. The cinema explodes, blowing the marquee off of the front, Shosanna‘s chorus giving its ultimate flourish.

The coda of Inglourious Basterds takes place in a forest at the Allied lines, where Landa will surrender to Raine and Utivich. Before allowing him to do so, though, Lt. Raine reprises his swastika-carving sub-theme from Chapter 2, as the voice of the film’s titular characters makes its final statement, and Landa‘s is finally silenced.

Previously we looked at Chapters 1 and 2 of “The Inglourious Fugue.” In this post, we’ll look at Chapters 3 and 4, which loosely correspond to Act II in the traditional screenwriting structure. Refer to my intro for a definition of the terms being used here and an outline of how we’re looking at Inglourious Basterds as a fugue.

Chapter 3: German Night in Paris

After a great crane shot of the cinema to open the chapter—a trademark Tarantino fetishization—the voice of Shosanna is re-introduced, now in the key of Emmanuelle Mimieux. (QT’s title card tells us that this is four years after the events in Chapter 1, although the dates given—1941 and June of 1944—don’t quite add up.) The cinema serves as Shosanna/Emmanuelle‘s chorus, and we also get a brief introduction to Marcel, her answer. While working on the marquee, Emmanuelle meets Fredrick Zoller, the first voice of the Nazis in this chapter.

After a great crane shot of the cinema to open the chapter—a trademark Tarantino fetishization—the voice of Shosanna is re-introduced, now in the key of Emmanuelle Mimieux. (QT’s title card tells us that this is four years after the events in Chapter 1, although the dates given—1941 and June of 1944—don’t quite add up.) The cinema serves as Shosanna/Emmanuelle‘s chorus, and we also get a brief introduction to Marcel, her answer. While working on the marquee, Emmanuelle meets Fredrick Zoller, the first voice of the Nazis in this chapter.

The next day, In the coffee shop, Shosanna again encounters Zoller, and this time his voice overtakes hers and becomes dominant as he expands his subject, showing its full nature (namely, that he is a German war hero, and the star of a new propaganda film about his exploits).

The next day, In the coffee shop, Shosanna again encounters Zoller, and this time his voice overtakes hers and becomes dominant as he expands his subject, showing its full nature (namely, that he is a German war hero, and the star of a new propaganda film about his exploits).

There is another interlude at the cinema, and then Shosanna is taken by some Nazis to a restaurant, where she meets Joseph Goebbels, whose voice is immediately and strongly established with a small racist monologue about American Olympic gold being earned with Negro sweat.  Goebbels and Zoller then play off of each other, their two voices harmonizing as they discuss the premiere, while Shosanna is drowned out. Major Hellstrom also makes an appearance here, briefly foreshadowing his voice, which will become a foreground subject for a time in Chapter 4.

Goebbels and Zoller then play off of each other, their two voices harmonizing as they discuss the premiere, while Shosanna is drowned out. Major Hellstrom also makes an appearance here, briefly foreshadowing his voice, which will become a foreground subject for a time in Chapter 4.

Chapter 3’s Nazi subject peaks when Landa enters and reasserts his voice by ordering a glass of milk for Shosanna, and again when he makes a big show of ordering cream for their strudel, both callbacks to Chapter 1.  (I love how he attacks his strudel with his fork; it’s a very brief moment, but very effective at foreshadowing the kind of violence he’s personally capable of, which we’ll get to witness first-hand in Chapter 5.) Landa also recapitulates Goebbels‘ racism sub-theme, remarking that being a projectionist would be a good job for “them” (Negroes). This scene is full of tension, with Landa‘s sly smirk and pleasant facade undermining his true nature, which we were witness to in Chapter 1, and contrasting with Shosanna‘s inner struggle to remain calm, which her face almost betrays—Mélanie Laurent is unbelievable in this scene.

(I love how he attacks his strudel with his fork; it’s a very brief moment, but very effective at foreshadowing the kind of violence he’s personally capable of, which we’ll get to witness first-hand in Chapter 5.) Landa also recapitulates Goebbels‘ racism sub-theme, remarking that being a projectionist would be a good job for “them” (Negroes). This scene is full of tension, with Landa‘s sly smirk and pleasant facade undermining his true nature, which we were witness to in Chapter 1, and contrasting with Shosanna‘s inner struggle to remain calm, which her face almost betrays—Mélanie Laurent is unbelievable in this scene.

When Landa finally exits, Shosanna is at last allowed to let out a gasp, releasing the tension that had been established. We then jump to later that night, as Goebbels, Zoller, and a few other Nazis come to check out the cinema. While they’re attending a screening, Shosanna reveals to Marcel her plan to burn it down while the premiere is taking place, setting in motion the first of two assassination plots that will be undertaken in Chapter 5.

Chapter 4: Operation Kino

Finally, the fourth and final primary voice is introduced, as Lt. Archie Hicox is recruited by General Ed Fenech to take part in Operation Kino. Outside of the small tavern in the village of Nadine, the Basterds re-state themselves, and begin to harmonize with the voice of Operation Kino as Hicox joins their ranks.

Finally, the fourth and final primary voice is introduced, as Lt. Archie Hicox is recruited by General Ed Fenech to take part in Operation Kino. Outside of the small tavern in the village of Nadine, the Basterds re-state themselves, and begin to harmonize with the voice of Operation Kino as Hicox joins their ranks.

In the basement tavern, we meet Bridget von Hammersmark, who is fraternizing with some Nazis, her countersubject. The Kino–Basterds enter and von Hammersmark joins them. After some more banter, Major Dieter Hellstrom makes his presence known, asserting his voice against the Basterds‘ and von Hammersmark‘s. There is another scene of beneath-the-surface rising tension, much like the one between Landa and Shosanna in Chapter 3, as well as another recapitulation of the racism Nazi sub-theme when Hellstrom conflates “American Negroes” with King Kong. This time, the tension boils over when Hicox gives himself away by holding up the wrong three fingers.

In the basement tavern, we meet Bridget von Hammersmark, who is fraternizing with some Nazis, her countersubject. The Kino–Basterds enter and von Hammersmark joins them. After some more banter, Major Dieter Hellstrom makes his presence known, asserting his voice against the Basterds‘ and von Hammersmark‘s. There is another scene of beneath-the-surface rising tension, much like the one between Landa and Shosanna in Chapter 3, as well as another recapitulation of the racism Nazi sub-theme when Hellstrom conflates “American Negroes” with King Kong. This time, the tension boils over when Hicox gives himself away by holding up the wrong three fingers.

A shoot-out ensues between the Nazis, the Basterds, and Hicox, appearing to leave only Master Sgt. Wilhelm (the new father) alive. Lt. Raine‘s voice enters from the street above, establishing Tarantino’s requisite Mexican standoff (the only one, to my recollection, that is explicitly referred to as such in the film), which is brought to an abrupt resolution when von Hammersmark‘s voice re-asserts itself by shooting Wilhelm.

A shoot-out ensues between the Nazis, the Basterds, and Hicox, appearing to leave only Master Sgt. Wilhelm (the new father) alive. Lt. Raine‘s voice enters from the street above, establishing Tarantino’s requisite Mexican standoff (the only one, to my recollection, that is explicitly referred to as such in the film), which is brought to an abrupt resolution when von Hammersmark‘s voice re-asserts itself by shooting Wilhelm.

The end of Chapter 4 mirrors the end of Chapter 3, with a scene at the veterinarian’s office, where von Hammersmark‘s bullet wound is to be treated, during which the Basterds, along with von Hammersmark, hatch a plan of their own to blow up the cinema on the night of the premiere, as it’s revealed to us that Hitler will be in attendance. Landa‘s voice re-enters briefly in the tavern, where he retrieves the napkin that von Hammersmark had autographed, calling back to his assertion in Chapter 1 that he was a skilled detective.

Now the wheels are in motion for a climactic collision of the two separate assassination plots, and the stage is set for Chapter 5, which we’ll get to next.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Chapters 3+4

Refer to my “Inglourious Fugue” intro for an explanation of what’s going on in this post. Here we’ll turn to an analysis of the first two chapters of Inglourious Basterds, viewing its construction as a fugue.

Roughly speaking, Chapters 1 and 2 correspond to the traditional Act I, providing the setup for the film.

Chapter 1: Once Upon a Time… In Nazi-Occupied France

The film opens with an exposition, introducing the voice of Perrier LaPadite, which will quickly be drowned out by that of Col. Hans Landa of the SS. Landa gets ample time to establish himself as the primary voice of the piece, introducing several themes that will be revisited throughout.

The first chapter is a slow build, establishing the tone of the film as a spaghetti Western that happens to take place during WWII (Chapter 1 is an homage to The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly). Landa‘s voice gradually establishes itself at the house of LaPadite, making its first flourish when he pulls out his giant pipe in a peacock-like display of masculinity. As Landa and LaPadite converse, the camera slowly drops down beneath the floorboards to show us the Dreyfus family hiding underneath, introducing the first (and primary) countersubject to Landa. There’s also a minor answer to Landa that pops up here, when he asks for a glass of milk.

Tarantino’s camera spins around the table as the Landa voice flits about with his monologue about the Germans (hawks) and the Jews (rats), creating dissonance within the subject. The Nazis enter the house, establishing themselves as an answer to Landa‘s subject, and we catch another glimpse of the Dreyfus’ eyes through the floorboards, which counterpoint the Nazis’ sub-voice as well.

The Nazis’ voice peaks when they machine-gun the floor, killing all of the Dreyfuses except for Shosanna. As Shosanna escapes, her voice in the first chapter peaks. Landa‘s own subject rises as she runs across the field, fading out quickly after he chooses not to fire his Luger into her back, having fully established itself.

Chapter 2: Inglourious Basterds

In Chapter 2, a new voice is introduced, with Lt. Aldo Raine giving his recruiting speech to the rest of the Basterds. This is abruptly met with a countersubject when we cut to Hitler screaming, “Nein! Nein! Nein! Nein! Nein!”  Here Hitler is serving as the same element as Landa did in the first chapter, as if to restate the same theme, this time in a different key. He interrogates Pvt. Butz, a sub-voice, on his encounter with the Basterds, and as Butz relates his tale in flashback, the two subjects of Chapter 2 play against each other.

Here Hitler is serving as the same element as Landa did in the first chapter, as if to restate the same theme, this time in a different key. He interrogates Pvt. Butz, a sub-voice, on his encounter with the Basterds, and as Butz relates his tale in flashback, the two subjects of Chapter 2 play against each other.

Tarantino cuts between Butz telling the story to Hitler and the images of the Basterds carrying out the deeds he’s describing. The Basterds‘ voice flourishes with the story of Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz as a flashback-within-a-flashback, which QT handles effortlessly (as he also did in Kill Bill Vol. 2).

We then get another answer to the Nazi/Hitler subject in the form of Sgt. Werner, who is quickly overshadowed by the voice of Lt. Raine.  The peak of Chapter 2 for the Basterds comes when we’re introduced to Sgt. Donny Donowitz (“The Bear Jew“), who is commanded by Raine to oblige Werner‘s desire to die for his country, which he happily (and brutally) does.

The peak of Chapter 2 for the Basterds comes when we’re introduced to Sgt. Donny Donowitz (“The Bear Jew“), who is commanded by Raine to oblige Werner‘s desire to die for his country, which he happily (and brutally) does.

For the rest of the scene, QT again cuts back and forth between Butz telling his (abridged) story to Hitler and Raine completing the Basterds‘ subject for this chapter. The swastika-carving answer to the Basterds‘ subject is introduced as Chapter 2 winds down.

At this point, three of the fugue’s four primary elements have been established, and the tone of the overall piece has been set. In the next post, we’ll look at Chapters 3 and 4, where the stakes are increased significantly, and the structure continues to become more complex.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Chapters 1+2

In my review of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, I mentioned that the narrative is constructed like a fugue. As I said, I find this to be a fascinating structure, so I wanted to explore it in depth, both to point out exactly what I meant by it—to clarify the point I was making—and to solidify my interpretation of the screenplay’s assembly.

By their nature, these posts will be rife with spoilers.

There’s a pretty detailed Wikipedia article on fugues, and there’s a better overview on this page, but they’re more technical than I’m going to get. (While there was a point in my life that I had a pretty sophisticated formal music education, it’s been almost a decade now since I’ve studied music academically, and I’m not going to pretend to remember the intricacies or formalities of musical analysis. Besides, that’d make for much more boring posts.) What I am going to do, though, is to speak of the characters in Inglourious Basterds as if they were musical voices, and (hopefully!) show how they enter, exit, intermingle, and eventually come together much in the style of a quadruple fugue. I’m focusing on structure here, and won’t endeavor to belabor my metaphor even further by trying to fit the various appearances of the characters into any more of the formally-defined fugal actions beyond the structural and superficial ones.

The language of musical theory has a lot of variations, so to try to keep things from getting too confusing and complicated, here are the main terms I’m going to use and how I’ll use them:

- A subject is a primary melody, sometimes also called a voice or an element. It’s introduced and then re-visited throughout the piece, often in different keys, typically becoming dissonant at one point before eventually being resolved in its initial key.

- An answer or counterpoint is like a sub-subject. It’s another way of stating the same musical idea, usually in a different key, or shifted on the scale. It’s not as fully-developed as the subject, but its presence helps to enhance the subject.

- A countersubject is a voice that contrasts with the subject, generally by conveying an opposing style or idea. Sometimes a melody (character) will appear as the countersubject in one movement (chapter), but as the primary subject in another.

Because I find the terms counterpoint and countersubject to be confusing (they have almost completely opposite meanings, despite their syntactical similarities), I’ll prefer to use answer or sub-voice to describe a thematic element (character) that reinforces a subject, avoiding counterpoint altogether.

The four voices in Inglourious Basterds, as I see them, are:

Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz): Introduced at the start of the film in Chapter 1, Landa is the primary and most constant subject throughout the story. His sub-voices are Goebbels, Hitler, and the rest of the Nazis that appear throughout the film. He appears prominently in Chapter 1; he’s re-introduced in Chapter 3; one of his sub-voices is especially present in Chapter 4, the end of which sees him taking its place; he’s present throughout Chapter 5, along with all of his sub-voices, and finds his resolution when he captures Lt. Raine; his voice is found echoing until the very end, in the forest coda.

Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz): Introduced at the start of the film in Chapter 1, Landa is the primary and most constant subject throughout the story. His sub-voices are Goebbels, Hitler, and the rest of the Nazis that appear throughout the film. He appears prominently in Chapter 1; he’s re-introduced in Chapter 3; one of his sub-voices is especially present in Chapter 4, the end of which sees him taking its place; he’s present throughout Chapter 5, along with all of his sub-voices, and finds his resolution when he captures Lt. Raine; his voice is found echoing until the very end, in the forest coda. Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent): Introduced at the end of Chapter 1 as a countersubject to Landa, Shosanna is re-introduced in a different key as Emmanuelle Mimieux in Chapter 3, where her sub-voice is Marcel (Jacky Ido), and her countersubject is Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl). She’s re-introduced again in Chapter 5, where her voice reverts back to its original key after she’s been shot, as her face—as Shosanna again—appears on the screen (and in the smoke).

Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent): Introduced at the end of Chapter 1 as a countersubject to Landa, Shosanna is re-introduced in a different key as Emmanuelle Mimieux in Chapter 3, where her sub-voice is Marcel (Jacky Ido), and her countersubject is Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl). She’s re-introduced again in Chapter 5, where her voice reverts back to its original key after she’s been shot, as her face—as Shosanna again—appears on the screen (and in the smoke). The Basterds: Introduced in Chapter 2, with Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt) as the primary subject. The sub-voices are the rest of the Basterds, specifically Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz (Til Schweiger), Sgt. Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth), and Pfc. Smithson Utivich (B.J. Novak). There’s also a thematic answer in Raine’s habit of carving swastikas into the foreheads of the Nazis he allows to survive. The Basterds are re-introduced in Chapter 4, where their countersubjects are the Nazis in the tavern and Landa. Their voice is resolved in Chapter 5, with an echo of their sub-voice serving as the film’s coda.

The Basterds: Introduced in Chapter 2, with Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt) as the primary subject. The sub-voices are the rest of the Basterds, specifically Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz (Til Schweiger), Sgt. Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth), and Pfc. Smithson Utivich (B.J. Novak). There’s also a thematic answer in Raine’s habit of carving swastikas into the foreheads of the Nazis he allows to survive. The Basterds are re-introduced in Chapter 4, where their countersubjects are the Nazis in the tavern and Landa. Their voice is resolved in Chapter 5, with an echo of their sub-voice serving as the film’s coda. Operation Kino: This subject is introduced in Chapter 4 via Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender), when he’s briefed by General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers), and is then re-introduced as Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger) in the tavern scene, where the Nazis (and later Landa) are the countersubject. The Kino voice becomes intertwined with those of the Basterds and Shosanna in Chapter 5, and all three reach their resolution simultaneously during the film’s climactic scene.

Operation Kino: This subject is introduced in Chapter 4 via Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender), when he’s briefed by General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers), and is then re-introduced as Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger) in the tavern scene, where the Nazis (and later Landa) are the countersubject. The Kino voice becomes intertwined with those of the Basterds and Shosanna in Chapter 5, and all three reach their resolution simultaneously during the film’s climactic scene.

I’m using colors to try to help distinguish the various voices and sub-voices, so I apologize to anybody who might be color-blind. I’m sure there’s a more accessible way of doing this that I’m not aware of.

So hopefully now the stage is set. I’m splitting this up into multiple parts, like Todd Alcott does, in the hopes of aiding in readability. In the next post we’ll take a look at the first two chapters of Inglourious Basterds, with all of this in mind.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Intro

Status: In theaters (opened 8/21/09)

Directed By: Quentin Tarantino

Written By: Quentin Tarantino

Cinematographer: Robert Richardson

Starring: Brad Pitt, Christoph Waltz, Mélanie Laurent, Diane Kruger, Daniel Brühl

I often wonder what it would’ve been like to have lived through the careers of some of the great filmmakers of the past, watching them develop as they went along, refining and honing their craft with each successive film. How great would it have been to see, say, North by Northwest on opening night? Today we are lucky to have a few visionary writer-directors who are making their mark on the history of film in their own right—PTA, the Coens, Lynch, Lee—as well as a few still-working old-timers who serve as a bridge between modern times and previous eras of film—Lumet, Scorsese, Allen. I firmly believe, though, that the single most defining voice of modern-day American film is that of Quentin Tarantino, and getting to watch him develop as a filmmaker is one of the greatest cinematic pleasures to be found thus far in the 21st century. His newest film, Inglourious Basterds, demonstrates his maturation in several regards, most notably as a more-refined version of several of the stylistic devices he began exploring with the Kill Bill films. The word “masterpiece” doesn’t quite apply here, but only because it might imply that his previous works are somehow not as accomplished. They are the lot of them all masterpieces to one extent or another, but his newest offering comes as Tarantino’s most concentrated effort, simultaneously pushing new boundaries while re-addressing familiar territory with the confidence of an artist who has a focused, ambitious vision—and the wherewithal to execute on it.

Inglourious Basterds is told as a fugue in five parts. The first four of the demarcated chapters each introduce a particular voice along with its counter-melody, so to speak, and the fifth sees them all come together, twisting upon each other until everything comes to a head. There’s even a coda to wrap it all up with an echo of an earlier sub-theme. It’s a remarkable storytelling structure, not just for its complexity and the ease with which Tarantino keeps all of the characters’ interests present, but also for the tact with which he interweaves them together until they all spiral around each other, becoming entangled and overlapping and feeding back on themselves, leading to what is destined to be counted as one of the most absolutely satisfying climaxes there’s ever been in a film.

Brad Pitt gets top billing because he’s Brad Pitt, but he’s really only one of several primary voices in an ensemble—and global—cast. In Chapter 1, we meet Colonel Hans Landa of the SS (Christoph Waltz)—”The Jew Hunter”—who has been charged with rounding up any remaining Jews in Nazi-occupied France. His counterpoint is Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent), a Jew who escapes to Paris. In Chapter 2, we meet the “Basterds,” a group of Jewish-American soldiers assembled by Lieutenant Aldo Raine (Pitt) who mercilessly hunt down, murder, and scalp German soldiers. In Chapter 3 we learn that, three years later, Shosanna is now posing as the owner-operator of a Parisian cinema. She catches the eye of a German war hero named Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl), who is the subject and star of the newest propaganda film produced by Joseph Goebbels (Sylvester Groth). In Chapter 4 we become privy to an Allied plot involving a turncoat German actress named Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger). And in Chapter 5, all of these threads come together, as the interests of each of these characters intersect.

Tarantino weaves these stories around each other, and when it’s all said and done, they’re each resolved one way or another at the film’s climactic conclusion. Up to that point, tension is built on many levels, leading to a release unlike any other. Tension is definitely the name of the game here. Tarantino has re-teamed with his Kill Bill cinematographer Robert Richardson, and that collaboration has again resulted in a creatively- and beautifully-shot film. The familiar Tarantino technique of the camera encircling a table takes on a new meaning here, with faster revolutions increasing the tension of an interrogation scene, or slower movements achieving the same effect in a claustrophobic barroom standoff. Scene after scene is a textbook example of how to create suspense, with the fugue-style construction applying also to the pattern of tensions and releases, each segment developing and resolving its own minor conflict while also contributing to the overarching buildup of the primary plot thread.

Like Kill Bill, Inglourious Basterds is primarily a revenge tale. If there’s a main story to speak of, its heroine is Shosanna, and its antagonist is Col. Landa. In a cast that has few performances that are anything less than great, Mélanie Laurent and Christoph Waltz especially stand out, the latter in particular giving a command performance that sees him speaking no fewer than four languages fluently—and menacingly. This isn’t to say that Brad Pitt isn’t good—he is; in fact, it’s one of his best performances, and probably his most amusing. The cast is rounded out by some fun surprises: horror director Eli Roth as “The Bear Jew” Donny Donowitz (father of the cocaine-purchasing producer from True Romance), Mike Myers in a nice non-comedic turn as an English General, and some uncredited voice work from familiar Tarantino alums Sam Jackson and Harvey Keitel. Tarantino gets away with stylistic flourishes like humorous (and superfluous) titles in the middle of scenes and unevenly-used narration precisely because he has the chutzpah to use such devices when they’re not expected, and to do so reservedly, using them as an enhancement to the presentation of his tale, rather than as a crutch to lean on in the telling of it.

The soundtrack is decidedly Tarantino, featuring an eclectic mix that’s at once anachronistic and yet appropriately fitting. The musical themes during the Basterds’ scenes are similar to those from Kill Bill, but most of the rest of the score is of the spaghetti-western variety—there’s even a fair helping of Ennio Morricone, the godfather of the style. Elsewhere there are punctuations of blaring rock music, highlighted by a Bowie song that manages to fit quite well, given the context in which it’s used (“putting out fire with gasoline,” indeed).

Quentin Tarantino is undeniably one of the most talented filmmakers working today, not to mention one of the most creative, original, and unique. Each of his films has been at once a celebration of the history of cinema (of which he has an encyclopedic knowledge), as well as a significant and noteworthy new contribution to that very history. After Pulp Fiction made him a household name 15 years ago, the questions being asked where, “Did he peak too soon?” and “Where will he go from here?” I don’t think anybody could’ve imagined at the time what the answers to those questions would end up being, and indeed we probably don’t know them fully still. He’s unquestionably an artistic genius, and one of the preeminent filmmakers working today. The final line of dialogue in Inglourious Basterds is, “This just might be my masterpiece.” It’s not spoken by Tarantino (he doesn’t appear as an actor in the film), but it might as well be. I’d be hard-pressed to disagree with him.

Status: In limited release (opened 6/12/09)

Directed By: Duncan Jones

Written By: Nathan Parker

Cinematographer: Gary Shaw

Starring: Sam Rockwell, Kevin Spacey

It’s a timeless question of philosophy: what makes me “me”? Duncan Jones’s Moon presents this question by adhering to a timeless rule of cinema: show, don’t tell. Its main character, Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), doesn’t ask the question directly, but rather raises several of its implications through his actions and the situations the film puts him in.

Stationed on the dark side of the moon, nearing the end of his 3-year stint mining helium-3 for power, Sam lives alone in a corporate outpost. His isolation is compounded by a perpetual outage of the live communications link between his base and Earth. He communicates with his wife and child back home by exchanging video messages with them, which take several hours to be delivered. His only company is a robotic computer named Gerty (voiced by Kevin Spacey). I don’t know if this is meant to be a reference to E.T. or not, but I wouldn’t put it past Duncan Jones. His film is firmly grounded in the canon of classic science fiction, and he pays homage to several forebears of the genre respectably and tastefully—most notably Kubrick’s 2001, which any film involving a ship-board computer automatically invokes. The script by Nathan Parker, from a story by Jones, knows exactly what it’s inciting in the minds of its audience every time Gerty interacts with Sam, and it plays with these expectations in a very fun way. We’re constantly expecting the “I can’t let you do that, Dave” moment, but all Gerty wants to do is help. His emotions are conveyed by a small screen depicting a yellow smiley face, which changes to a frown when he’s trying to empathize with Sam.

Only two weeks away from his scheduled time to finally return home, Sam sets out in a moon rover and has an accident. Then something strange happens, and that’s all I’ll say about the plot. The whole premise of this film is a joy to watch unfold and become lost within. As I say, it deals with timeless philosophical questions, and it presents them naturally in the context of its story. It’s thoughtful, it’s intriguing, it’s existential, and it’s thoroughly engrossing.

Sam Rockwell is nothing short of amazing in this film, though I’ve come to expect that of him. He’s the only actor on screen for about 95% of the movie, and not a second of it is boring or tedious. Jones’s direction is tasteful, allowing Rockwell’s presence to dominate, while cleverly milking the setting for tension every chance he gets. Spacey’s voice work, too, is haunting—while the obvious comparison for Gerty is to HAL 9000, he more brought to mind for me the old man from the end of David Lynch’s The Straight Story, a character whose calmly soothing speech and apparent lack of an ulterior motive only serves to make him all the more creepy.

The style of Moon is refreshingly retro, in that it creates a world to tell a story within and never pulls you out of it, and it does so honestly. There is no CG that I could detect; the film is shot on soundstages, using handmade models when needed, the way real movies used (and ought) to be made. The special effects are completely seamless, not calling attention to themselves but merely serving to enhance the setting and the story—again, the way it should be. The set design is detailed and realistic, with the moon base where Sam works feeling lived-in in the same way the Nostromo from Alien did. There are clever and loving touches sprinkled everywhere, from rations of beans stacked against the walls to a “KICK ME” Post-It note stuck to the back of Gerty the robot.

Attention to detail everywhere fills out this world. Watch closely when Sam first draws smiley faces on the metal wall of his shower. There’s a subtle clue there of what’s to come that won’t make sense until later—indeed, it may even seem like sloppy editing at first—but it’s a great sign of the care that went into crafting this story, and the thought that went into its production. There are layers and layers of details to be peeled back.

The score, by Clint Mansell, is appropriately haunting and ambient, helping to set the tone and assisting in creating the film’s tension. Mansell is familiar to me for having scored all of Darren Aronofsky‘s films, most notably to the topic at hand The Fountain. That film, too, dealt with existential dilemmas and shared a similar theme with Moon of the most basic desire of life, which is to continue living.

Moon is the feature directorial debut of Duncan Jones, who happens to be the son of David Bowie. This fact isn’t really relevant to the film, but it’s interesting nonetheless. What is relevant is that this is an impressive movie, both for its concept as well as its execution. That it’s Jones’s first only serves to underscore its achievement. I’d like to say more about Sam Rockwell’s performance in this movie, but to do so would be to give away what I consider to be some fundamental spoilers. Suffice it to say that he’s as good as he’s ever been, which is to say that it’s as good of a performance as you’re going to see right now. He and Jones are a perfect match here, and Moon is the wholly entertaining fruit of that partnership.

Comments Off on Dark Side

This is the second entry in an ongoing series.

Timothy Olyphant is an actor who’s been around for a while, but it doesn’t seem like he’s as well-known as he should be.  He’s an excellent actor who’s had a wide variety of roles, and for that very reason I find him to be a great fit for a Found Role. Though he’s not as known as I personally think he should be, most people will probably be able to recognize him as Thomas Gabriel, the bad guy from Live Free or Die Hard.

He’s an excellent actor who’s had a wide variety of roles, and for that very reason I find him to be a great fit for a Found Role. Though he’s not as known as I personally think he should be, most people will probably be able to recognize him as Thomas Gabriel, the bad guy from Live Free or Die Hard.

As the cyber-terrorist who torments John McClane by hacking into and shutting down vital public works, Olyphant is creepy and menacing—and just the right amount of campy, too. It’s the fact that he plays such a bad-ass in Die Hard 4 that makes this particular earlier role so amusing to me.

I didn’t really intend for the entries in this series to segue into each other, but this one just so happens to follow nicely from the previous entry. That one featured Jon Favreau, who wrote and starred in Swingers, which was directed by Doug Liman. Here, we turn to Liman’s subsequent film, an oft-overlooked gem from the late 1990s called Go.

A drug-addled, raver-centric, Rashômon-style tale of a single night in the intersecting lives of several young people, Go‘s story begins with a deal gone wrong. Indie darling Sarah Polley goes over the head of her absentee dealer, making a buy directly from her local small-time kingpin named Todd Gaines, played by Olyphant. The film takes place during the holidays, and in the clip below you can see that Gaines is clearly in the holiday spirit as he interrogates Claire (a young Katie Holmes), who’s been left with him as collateral while Polley’s character Ronna goes to get the rest of the money she owes him.

While I obviously realize that it shouldn’t be particularly noteworthy that a good actor is able to play both a crazy-eyed drug dealer and a cold-blooded cyber-terrorist, and play both convincingly (that’s what good actors do!), recognizing this doesn’t make the contrast any less amusing. A large part of what I’ve intended to be the fun of this series comes from having the benefit of hindsight to compare a now-accomplished actor’s roles with where he or she started out.

I also didn’t mean for these to be particularly timely, but the Breakfast Club reference happens to fit with the recent news of the death of John Hughes, the writer and director of that film. Timothy Olyphant is currently featured as one of the headliners in the thriller A Perfect Getaway, which was just released. I’ve not seen it, but that film appears to cast him as another demented criminal, albeit one who operates on a smaller scale than did his Thomas Gabriel. It seems he’ll continue to have a fruitful career ahead of him, but I hope he doesn’t end up being repeatedly typecast as the consummate psycho evildoer; obviously he’s capable of much more—such as a Santa Claus hat-wearing drug dealer with a hidden heart of gold.

Status: In limited release (opened 6/26/09)

Directed By: Kathryn Bigelow

Written By: Mark Boal

Cinematographer: Barry Ackroyd

Starring: Jeremy Renner, Anthony Mackie, Brian Geraghty

To paraphrase Boogie Nights, everybody is good at one special thing. For Staff Sergeant William James (Jeremy Renner) in Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, that one thing is dismantling bombs, specifically the improvised explosive devices that plague post-invasion Iraq. He takes over as leader of Bravo Company in Baghdad in 2004, as their year-long tour of duty is nearing its end. Along with Sergeant Sanborn (Anthony Mackie) and Specialist Eldridge (Brian Geraghty), James responds to reports of discovered or suspected IEDs and does the dirty work of disarming them on the spot. As we meet up with him, he’s already done this 873 times, each time putting his life at risk, and he shows no desire to give it up any time soon.

Baghdad in the wake of the U.S.-led invasion seems like no place to live, and most of its inhabitants don’t appear to particularly care if they do. There are burned-out buildings, death and destruction everywhere, and the city is littered with IEDs, giving Bravo Company plenty of work to do, and James in particular never wastes time diving right in. Explosive Ordnance Disposal isn’t just his job, it’s his lifeblood, his purpose, and his obsession.

The title of The Hurt Locker comes from a poem by Brian Turner, who writes based on his experiences as a soldier in the Iraq war. The film’s screenwriter, Mark Boal, spent time in Iraq with an EOD squad, and the reality of those experiences shows through. It opens with a quote proclaiming that war is a drug, and nowhere is that more apparent than in the actions of Staff Sergeant James. Renner injects him with the obsessive qualities of an addict, a man who is not just good at what he does, but needs desperately to do it. He gets off on it. He keeps a souvenir piece of every bomb he’s dismantled under his bed, as if they were notches in his bedpost.

James won’t leave until he’s accomplished his mission, no matter the cost or the risk to himself and his unit. When a particularly clever car bomb has him stumped, he ignores the imminent danger around him and the pleas of his company, feverishly working until he’s overcome the challenge of figuring out and conquering the device, getting his fix in the process. When he believes a village boy he’s befriended to have been murdered, he breeches protocol, leaves base, and invades an innocent professor’s home to try to find the killer. Then he gets up the next morning, dons his bombsuit, and goes to dismantle another IED. He’s obsessed to the point of becoming a man with a singular function. Ask him to save hundreds of lives while the clock is ticking, and he’s focused and unflappable. Ask him to pick up cereal at the grocery store, though, and he’ll stand in the aisle, dumbfounded by the myriad choices.

Bigelow and her cinematographer Barry Ackroyd shoot with a combination of dramatic and documentary styles, and the mix works perfectly. We see scenes of Bravo’s humvee trailing a cloud of sand across vast desert landscapes and shootout sequences that put us right in the middle of the action. Then we ride along in that Humvee, bouncing with the terrain, as Sanborn reveals his dreams and Eldridge his fears. Some sequences are beautifully cinematic, others are very down-and-dirty. The focus is always on these men and what they do and their motivations and the challenges they face.

The cast all around is excellent. The three relatively unknown actors who make up Bravo Company never imbue their characters with cliches, though they each are presented as a slightly simplified and generalized type of soldier so as to amplify the personality traits being depicted. Guy Pearce and Ralph Fiennes head the supporting cast, and both are as good as usual. And it’s amazing what Evangeline Lilly conveys in but a small amount of screen time.

The primary emotion of this film is suspense, and it builds it constantly and effectively. Bigelow knows just how to structure a scene to maximize the tension of the situation, focusing on the task at hand and then cutting to the surroundings at just the right times. We feel the claustrophobia of James’s bombsuit, we share the tension felt by Sanborn and Eldridge, and we feel the suspense of knowing that the bomb may go off at any moment. The film establishes early on—in its introductory scene, in fact—that we can never assume that any member of the team is indispensable, that any character is immortal. There’s another scene of an ambush in the desert that ends up in a standoff that lasts until dusk, and the exhaustion—not to mention the thirst—of the soldiers who are pinned in is almost as overwhelming to the audience as it is to them. It’s effective filmmaking, not just because of its subject matter, but because we care about its subjects and what might happen to them, and feel that we’re all too familiar with the stakes.

The Hurt Locker is one of the best war movies I’ve ever seen, and probably the best movie so far this year of any genre. It isn’t about the war, it’s about the warriors. It not only makes us sympathize with their situation, but it makes us feel that we’ve gained a small amount of understanding of it, and some empathy as well. It’s focused and unflinching in its depictions of its characters, and far-reaching in the precision of the emotions it invokes. War is a drug, and James is an addict, and The Hurt Locker helps us understand just exactly what that might actually mean.

Status: In theaters (opened 7/31/09)

Directed By: Judd Apatow

Written By: Judd Apatow

Cinematographer: Janusz Kaminski

Starring: Adam Sandler, Seth Rogen, Leslie Mann, Eric Bana, Jason Schwartzman, Jonah Hill

If there’s a canon of movies about comedians, I’m sure Scorsese’s The King of Comedy tops the list, but Judd Apatow’s third film, Funny People, is right up there. It’s a film that’s touching when it wants to be, depressing at times, insightful at others, and funny throughout.

The film stars Adam Sandler as George Simmons, a comedian-turned-actor who’s a lot like Adam Sandler. This isn’t a bad thing: part of the film’s charm is that it gives us a taste of what life is like for a mega-star of Sandler’s fame and celebrity. We see people pulling out their cell phones and snapping his picture everywhere he goes, others who come up and ask for a photo with him or an autograph, and leering onlookers every time he ventures out in public. We also get to see his circle of famous friends, providing ample opportunities for humorous cameos and a long section of credits of Himselfs, ranging from other comedians and actors (and comedian-actors) to a certain musician whose very presence in the movie is funny in and of itself, but the role has some added humor to throw in as well. (This could actually be said of two musicians who appear in Funny People, come to think of it.)

Early on in the film, George Simmons learns that he has a rare form of leukemia, and is put on experimental medication that gives him an 8% chance of overcoming it. Spurred by this shocking news, he assumes an all-too-understandably reflective mindset, revisiting the One Who Got Away (Leslie Mann) and returning to his stand-up comedy roots. After a painful improvisational set at an L.A. comedy club, a young up-and-comer named Ira Wright (Seth Rogen) catches his eye, and the two develop a working relationship that quickly blossoms into friendship.

The story of Ira and George forms the crux of Funny People‘s plot for the first half of the film, and despite the underlying morbid basis of their relationship, Rogen and Sandler are thoroughly enjoyable to watch as they interact and play off of each other. Sandler in particular really gets to show his range as an actor, exhibiting more of the kind of acting chops we saw in Reign Over Me than the crazy antics of his more typical Zohan fare. The surprisingly-skinny Rogen complements him perfectly, showing that even while he might not be the sure-thing lead actor he was believed to be (as Zack and Miri Make a Porno proved), he’s as good of a second-billed star as there is out there today, and Funny People puts him squarely in his wheelhouse.

The supporting cast provides an abundance of comedic bolstering to the film, starting with Jonah Hill in his typical role, but also featuring Jason Schwartzman as the hilariously proud star of a cheesy TV sitcom. There’s also Aziz Ansari, the guy who’s probably best known for inciting some recent Internet outrage, cast true to life as a hack comedian, and his fellow “Parks and Recreation” cast member Aubrey Plaza. Schwartzman stands out with his characteristically spot-on deadpan delivery, but all of these performances contribute nicely to the total product.

Nearly stealing the show, though, is Eric Bana, as the Aussie husband of Leslie Mann’s Laura (the aforementioned One Who Got Away). The latter parts of the film focus on George’s attempts to win Laura back, providing some additional opportunities to further explore broader emotional pastures than your typical comedy would be willing to venture into. Bana’s presence makes sure to keep things from ever getting too serious, punctuating several scenes with a hilariously self-deprecating performance. The film as a whole, in fact, finds a near-perfect balance between drama and comedy, cementing its sources of humor in real-life situations and allowing both sides to amplify each other organically.

Judd Apatow once again has cast his wife and children here, as he did in Knocked Up. He shares this particular form of familial narcissism with Kevin Smith, but Apatow has the advantage of being married to an actress (Leslie Mann) who can actually act. The same, unfortunately, cannot be said of his kids, and his insistence on bringing them front and center for a significant period of time is probably Funny People‘s biggest shortcoming. There’s one scene that is particularly indulgent, featuring what I assume is an actual Apatow home video, but otherwise the kids are cute enough and their lack of acting chops are more or less easy to overlook, though it’d be preferable if overlooking them weren’t necessary in the first place.

As has been the case with his previous two films (especially Knocked Up), this movie is a bit too long, feeling as if Apatow never had an idea he deemed unfit for his theatrical cut. The pacing is pretty good overall, but there’s definitely a point at the start of the third act when the film comes to a screeching halt. It picks back up shortly after this, thankfully, and redeems itself with a resolution that feels realistic and not at all forced, sufficiently redeeming itself of this slight divergence.

I should also mention the pleasant surprise/slight disappointment that was afforded by Funny People‘s trailer. I loved finding that several of the jokes in the trailer were not in the film, allowing for a fresher first-viewing experience than you’re normally afforded with a movie that’s marketed as a comedy. I was a little disappointed, however, to find that the “jam session” scene (featuring Jon Brion, who I’m always a fan of) used a different song than that depicted in the trailer. I thought that Ringo Starr’s “Photograph” really fit the tone of the film perfectly, but it was used solely as a marketing device, rather than as an integral part of the movie. Small point to pick.

Apatow is almost doomed, in a way, to fight an uphill battle as a director, having hit a solid home run in his first directorial at-bat with The 40 Year Old Virgin. Funny People isn’t quite as good, but it’s damn close, and hopefully a sign that there’s still a lot left in the tank that is the comedic mind of Judd Apatow. He has yet to disappoint.

Comments Off on Every Time I See Your Face