Status: In theaters (opened 12/18/09)

Directed By: James Cameron

Written By: James Cameron

Cinematographer: Mauro Fiore

Starring: Sam Worthington, Zoe Saldana, Sigourney Weaver, Stephen Lang

You wouldn’t have a very hard time convincing me that Avatar was not, in fact, actually written and directed by James Cameron, but rather by an ambitious fan of his previous films. That fan remembers the highlights, but he doesn’t remember what made them highlights in the first place. He remembers some of the sharp dialogue, but hasn’t the writing ability to equal it, so he sticks with cliches from other movies he’s seen. He knows the basic pieces and characters of your typical action movie, but he doesn’t want to bother with having to explain how they all fit together; better to just throw everything you can think of onto the screen and assume the audience will kind of get what you were going for, since they’ve seen it so many times before.

That old piece of Ebert wisdom to which I often refer applies to Avatar as much as any other movie I can think of: it knows the music, but not the words. I have a pretty hard time believing that this was Cameron’s Chinese Democracy; it doesn’t seem at all like a story he felt compelled to tell, spending over a decade slaving over its details in order to bring his vision to life. Rather, it feels like a showcase for a couple of technological advancements he wanted to force into happening, and just as was the case when George Lucas tried such a feat, the result is a movie that feels half-assed in its conception, with special effects being the main—and only—draw. It seems only right that I discuss the visuals before even bothering with a story synopsis, as it’s clear that’s how Cameron approached the film himself.

Due to some scheduling confusion, when I saw Avatar on its opening day, it was the non-3D version. And as much as the thought of having to sit through its two-and-a-half-hour-plus running time made me wince, I felt like I couldn’t really comment on it unless I’d gotten the full experience, so I went and saw it again two days later. Besides, as someone who’s interested in the technology of film as much as I am the art of it (and who sees the two as being intimately connected), I felt like I had to see what “the future of movies” looked like. I’m glad I did; it earned the movie a full additional star from me. My earlier skepticism was only half founded: while the flim’s plot and story-telling devices are certainly nothing special (and, in fact, they’re considerably below par), the 3D technology employed for its production really is ground-breaking. Whereas previous 3D movies I’ve seen (Coraline, Up, A Christmas Carol—all of which were completely animated) liked to use the effect primarily as a gimmick (although, as CK pointed out, Up was the most measured such use), in Avatar it is an integral part of the film itself. Previous 3D offerings have mostly relied on creating distinct planes of depth, with the occasional object sticking out of the screen into the audience (the “woah, look out, it’s coming at you!” effect), and I’ve largely agreed with Ebert’s assessment of such technology. The 3D effect of Avatar, however, is almost completely continuous; it’s not used so much to selectively make things pop out of the screen, but rather to add depth to everything you’re seeing, making it feel like an actual world. It really does immerse the viewer in the movie, and it’s for that reason that my second viewing was much more enjoyable than my first. Seeing this movie in 2D, you’re aware of the fact that several shots are framed so as to provide maximum perceived depth for the viewer, but since you’re not getting the effect it feels hokey and distracting. In 3D, though, such shots effectively convey the scope of the world in which the film takes place, while adding to the audience’s sympathy with the characters as well.

That’s not to say that it’s flawless. This is a significant landmark in the development of this recent iteration of 3D movies, but it’s not the final product. They still haven’t figured out how to keep things looking right when they’re at the edges of the frame, especially those that you perceive as sticking out of the screen. Motion can also be awkward at times, making things blurry in a way that seems to “pull apart” the stereoscopic images, which is really distracting. This is most pronounced when the camera is panning and objects come into and out of the frame as it does so. (Note: I’m not sure if this only happens with my eyes, or everybody’s, but until the technology is advanced enough that it is effective for every audience member all the time, it still has some ways to go.) Seeing this movie in 3D, nonetheless, is a very impressive experience, and while I don’t know if it’s as “revolutionary” as the advertising would like you to believe, it’s certainly a very significant evolutionary step of this technology.

It’s a good thing, too, because if it weren’t for such technological achievements, Avatar would be a pretty awful movie. The plot is paper-thin and ill-conceived, the characters are bland and clichéd, and the dialogue is so bad it made me cringe on multiple occasions. This is probably James Cameron’s poorest screenplay (even counting Titanic), but as I said, it’s obvious that he wasn’t really concerned with the script in the first place. It takes place about 150 years from now, and humans are trying to mine a material called “unobtanium” (yes, that’s really what they call it) from the planet Pandora. It’s pretty strange how little people have changed in those 150 years; they still smoke cigarettes, for instance, and gun technology hasn’t advance much except that they’ve gotten a little bigger. Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) is an ex-Marine who signs on to control an avatar, which is a body of a native Pandoran—a Na’vi—that he operates while in a sort of trance (and when his avatar sleeps, that’s when he wakes up). He’s sent to befriend the Na’vi, in order to convince them to leave their home so that the company he works for can access all of that precious—and ridiculously valuable—unobtanium that’s to be found under the tree in which they live. He keeps a video log, which conveniently serves as the film’s narration. Worthington is respectable for the most part in this role, although he’s asked to act the fool on several occasions, and he sometimes forgets to speak with an American accent (as was also the case in Terminator Salvation).

![]()

Dunbar—er, Sully—takes to the Na’vi culture quite well, and gains their trust. He of course falls in love with one of them, the huntress Neytiri (Zoe Saldana), who also serves as his (and our) tour guide to Pandora and the Na’vi society. That society is basically a half-hearted amalgamation of Native American stereotypes; the Na’vi are in tune with their planet (which they call “Mother”), spiritual people who are guided by a shaman, nature-warriors who fight with bows and arrows and whoop and ululate, who feel remorse for the lives they take in order to feed themselves, and who share a very literal bond with the animals they ride. The out-of-control Colonel (Stephen Lang) calls them savages and wants only to annihilate them (without much purpose, I might add—the “unobtanium” provides only the thinnest of excuses for the majority of the film’s action). He does his best impression of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, mixed with every other stereotypical, generic military leader. In fact, pretty much every character in Avatar is either a clichéd stereotype, a blatant rip-off of a character from a more original film, or both. The dialogue is equally uninspired, the jokes falling flat and the attempts at earnestness coming across as unintentionally funny. The worst such examples are the multiple instances of Worthington’s avatar character raising his fist triumphantly and shouting the most un-heartfelt “YEAH!” you’ve ever heard. It’s impossible to even attempt to take seriously.

I usually don’t make out-and-out recommendations for movies, preferring instead to describe my personal assessments of them and leaving it to the reader to decide if he or she agrees with them or not. For Avatar, though, it’s pretty straightforward: if you’re interested in the special effects, particularly the 3D cinematography—both as an exhibition of the current state-of-the-art, as well as an indicator of the direction in which the technology is headed—then you owe it to yourself to see it, and to see it on the big screen. The spectacle will be good enough that the film’s other shortcomings—which is pretty much every other aspect—can be overlooked. Don’t bother seeing it in 2D, though, because in that format you’re forced to focus on the storytelling, which leaves a lot to be desired (not to mention you’ll also be distracted by the obviously made-for-3D components). Personally, I’m kind of glad, in retrospect, that I saw both versions; it was a pretty eye-opening experience.

As was the case on the eve of The Dark Knight‘s release, I once again find myself feeling like I’m missing something as I consider the imminent release of James Cameron’s Avatar. In this case, at least, I’m pretty sure I’m not alone, and the grand declarations of the film’s importance are mostly due to its marketing campaign, rather than premature fandom. Still, though, there’re some lofty claims being made about this movie and the effect it’ll have on the entire film industry, and I find myself dubious of most of them.

The two primary claims in particular—as I perceive them—are that Avatar:

- is somehow revolutionary in the world of film, and

- will make you really believe in 3D movie-making.

I sometimes think that #1 is referring to #2, but usually it’s stated as if there’s more to the “revolutionary” aspects of it than the 3D technology alone. One commercial that I keep seeing on TV proclaims, “Movies will never be the same.” And from the trailers I’ve seen, I’m just not getting what exactly that’s referring to. Here’s the final theatrical trailer:

Seeing that and the other trailers for Avatar has thus far inspired one big “meh” from me. I can see how it might look really cool to some people, in a Lord of the Rings, fantasy/sci-fi, ultra-nerd sort of way, but I don’t see much that makes me think it’s very “revolutionary.” The counterargument seems to be that I will understand when I see it in 3D, because the television commercials and theatrical trailers just don’t do it justice. I’m withholding judgment on that aspect (as well as all others, hopefully) until I see it… but I’m pretty skeptical about it. I have yet to be really blown away by any of the films I’ve seen in 3D recently, and in fact more often than not I’ve felt I would’ve enjoyed the film more had the distracting gimmick not been employed.

Another area in which this movie is supposedly mind-blowingly amazing is the special effects, and unless they’re using temporary effects for the marketing materials, I’m pretty sure I won’t be too impressed by those, either. I have a pretty straightforward personal rule about CGI: If I can tell it’s CGI, then it’s shit. The whole point of special effects is to make you believe that what you’re seeing is real, isn’t it? There’s no caveat to that: “It looks really good for computer graphics” means it doesn’t look good for reality.

Don’t get me wrong; I think some of those terrains, and the planet Pandora in general, and some of the ships and vehicles look pretty amazing—real, even. The Na’vi, however—the blue-green inhabitants of the fictional world in which Avatar takes place—don’t look any different from the silly video-game characters of Robert Zemeckis’s Beowulf, and the creatures they ride don’t look any better to me than the cartoonish bouncing beasts from Attack of the Clones. Particularly when the Na’vi move, or when they speak, I feel like I’m watching a cut scene from a new video game, not a cinematic film—especially not a “revolutionary” one. The defense of this is always along the lines of, “They’re not humans, so they don’t move like humans, that’s why it looks weird to you,” which of course is nothing but a cop-out.

The film’s plot, likewise, doesn’t look like anything we haven’t seen before. Not to go too far in judging the book by its cover, but from the voluminous marketing material to which I’ve been exposed, I’ve gotten the distinct impression that the story of Avatar isn’t much more than The Matrix meets Dances With Wolves. (Or, as South Park called it, Dances With Smurfs.) Other reports of confusion confirm that I’m not alone in this.

As usual, I’m trying to remain as objective as possible and reserve judgment until I’ve seen the film for myself—which I’m intending to do tomorrow, in Digital 3D, so as to get the full advertised effect. But I have a healthy amount of incredulity heading into it. James Cameron has made some truly iconic films in his career, and I’m willing to give him the benefit of the doubt until proven wrong (which Titanic, his last film—12 years ago—almost did). Reading his Playboy Interview, it’s hard not to catch at least a little bit of his excitement about this latest endeavor. I’d prefer to let history be the judge of its effect on the world of film, though… and that’ll have to start with its wide release tomorrow.

Status: In theaters (opened 12/4/09)

Directed By: Jim Sheridan

Written By: David Benioff

Cinematographer: Frederick Elmes

Starring: Natalie Portman, Jake Gyllenhaal, Tobey Maguire

In my review of The Hurt Locker, I gushed about how it produces an effective take on modern-day wars by making them personal and compelling its audience to sympathize with the soldiers who fight in them. Brothers takes a similar tack, but its focus is much narrower, and as a result we don’t come away feeling like we’ve learned much of anything about the bigger picture. Like The Hurt Locker, it is apolitical in its view of the war (which in this case is in Afghanistan, rather than Iraq). Its aim is not to provide a commentary on war itself, or any war in particular, but rather to evoke an emotional response to war in general and what it does to the people involved.

As the title makes obvious, it’s about a pair of brothers. The younger one, Tommy (Jake Gyllenhaal), is a ne’er-do-well bad boy who has just been released from prison after serving time for armed robbery. Sam, the older brother (Tobey Maguire), is a Marine who gets deployed to Afghanistan, and is believed to have been killed—and in order to talk about this film at all, I have to reveal that he actually isn’t. He’s captured and presumed dead, and just when his wife Grace (Natalie Portman) is beginning to cope with the loss of her husband—thanks to the help of Tommy—Sam gets rescued and returned home. Thoroughly traumatized by his ordeal, he has a hard time re-acclimating himself to the family life, which is complicated by his suspicions that his brother and his wife have gotten a little too close in his absence.

The screenplay by David Benioff, adapted from the Danish film Brødre, is the kind of writing that you feel is just jerking you around most of the time. When Sam returns home, it’s never made clear what kind of a relationship with his wife he has, as important a detail as this may seem. Do they resume sleeping together immediately? What does he do to re-insert himself into his children’s lives? He’s suspicious of his brother, in particular the role Tommy has taken on in helping out with his daughters and providing companionship for Grace, but the details are only explored by side effect. There’s a brief scene showing that he’s now uncomfortable with his wife seeing his body, scrawny and wounded as it now is, and that’s about it until things come to a head, leaving us to infer the specifics along the way.

The dialogue is also a bit over-dramatic, but the three leads are good enough to keep it respectable. While Tobey Maguire will get all of the attention for pulling the inverse Raging Bull and shedding a ton of weight between his early scenes and his later ones, I actually thought Natalie Portman and Jake Gyllenhaal did more to keep the film grounded. There’s a joke (popularized by Tropic Thunder) that playing a retarded person is a surefire way to secure an Oscar nomination, and I think drastic weight gain or loss is in that same category, but Maguire really does an impressive job with his character’s metamorphosis. His costars are even more impressive, though, for the more subtle transitions their characters go through, which are really the highlight of the film.

I may be wrong about one thing: when Sam gets back from Afghanistan, the townspeople repeatedly refer to him as a war hero in a manner that I took to be a bit derogatory (their characters are sincere in saying it, but I found myself wondering exactly what it was he’d done that was so hero-like—you’ll see what I mean—which, actually, may have been the film’s intention after all). Nonetheless, the primary focus of Brothers is on two young men whose lives are moving in opposite directions, and the woman who comes between them. As a film about a love triangle, it’s actually quite tame, and the strong leading cast is really all it’s got going for it, but they are good enough to keep things somewhat interesting.

Comments Off on Sibling Rivalry

Status: In limited release (opened 12/4/09); opens wide 12/25/09

Directed By: Jason Reitman

Written By: Jason Reitman and Sheldon Turner

Cinematographer: Eric Steelberg

Starring: George Clooney, Vera Farmiga, Anna Kendrick, Jason Bateman

Fewer men have accumulated 10 million American Airlines frequent-flyer miles than have walked on the moon. Ryan Bingham (George Clooney) wants to become one of that elite group. His profession dictates that he travel almost constantly. He lives out of a carry-on-sized suitcase, staying in a different hotel room every night. He has a side gig doing speaking engagements, where he extols the virtues of a life lived in isolation, free of the metaphorical baggage of possessions and relationships that so many of us carry. He practices what he preaches. To reach the 10-million mile mark requires flying a shade under 350,000 miles per year for 30 years, and he’s dead set on achieving that. When his boss (Jason Bateman) requires him to return to his company’s office in Omaha, where he keeps a studio apartment that’s even less inviting than the hotel rooms he typically stays in, it puts a cramp in his schedule. Even having a tryst with a fellow travel junky, the beautiful Alex (Vera Farmiga), doesn’t dissuade him: instead of altering their travel plans, they compare schedules and look forward to the next time they’ll happen to be in the same city.

Up in the Air is a double entendre of a title for Jason Reitman’s new film: literally, it’s about a guy who flies a lot, but figuratively, Ryan Bingham’s place in the world—and his outlook of it—is undecided, particularly in terms of what he’s looking for in a relationship. (The film’s poster refers to “a man ready to make a connection.”) His company hires a young hotshot, a recent college graduate named Natalie (Anna Kendrick), with some new ideas about how they should run things. To prove that she’s wrong, Ryan takes Natalie on the road with him, to demonstrate for her the disconnect between her theories and the real world. Reitman and co-writer Sheldon Turner’s script is careful to avoid the cliches of the mentor/mentee relationship, although as is always the case in situations such as these, it is inevitable that they both end up learning a bit from each other over the course of their journey. What it’s really about, though, is what they learn about themselves.

I’m being intentionally vague about the details of the story here, because I really think that Up in the Air is the kind of film that you should go into cold and just let it unfold in front of you without knowing where it’s headed. (Even mentioning the 10 million-mile number might be considered a bit of a “spoiler,” albeit not a very big one.) What I can tell you is that it’s an engaging story, one that is extremely well-told, and a film that’s very well-made. It’s shot non-obtrusively by Eric Steelberg, allowing the character performances—which are without a doubt the main draw—to be showcased, but there are a few nice artistic touches thrown in as well (I particularly liked a recurring motif of introductory aerial shots of the various cities Ryan travels to). The editing, too, by Dana Glauberman, is a terrific balance of restraint and the occasional stylistic indulgence—montages of the people Ryan encounters in his travels, and rapid-fire sequences showing how he packs. It all fits an overarching tone of methodical adherence to routine, which gets disrupted when Ryan begins to change his mind about the way he lives his life.

George Clooney is as good as always, embodying his always-perfect balance of winking confidence, cockiness, subtle humor, and emotional vulnerability. He’s matched step-for-step by Vera Farmiga, and watching the two play off of each other is a true cinematic pleasure. There’s a climactic scene near the end where the two actors’ facial expressions tell an entire story all by themselves. (As an aside, I can’t decide whether the makeup and costuming in The Departed did a great job of making Farmiga look younger than she is, or if those of Up in the Air did an equally good job of making her look older, or both, but I think I’m tending to believe that she’s just such a good actress that it’s due to her skill more than anything. My perception of the age of her characters in the two films is that there’s at least a decade between them, and I find that really impressive.)

The supporting cast is also quite good. Most of them are tasked with conveying some serious emotions on screen, and by and large they do so in a way that feels real without getting too cheesy or forced. Jason Reitman, I think, is one of those directors who a lot of people want to work with, and as a result there are actors in Up in the Air‘s smaller supporting roles who are used to a lot more screen time (J.K. Simmons, Zach Galifianakis), but they pour themselves into their roles here just as well as they would otherwise. Most impressive, though—and most surprising—is Danny McBride, who I normally view as an annoying buffoon whenever he shows up in a film, but here Reitman reins him in, and he gives a whole-hearted performance that is central to making the movie’s emotional weight work.

Up in the Air is one of those films that has something for everybody. It’s equal parts funny, witty, insightful, heart-wrenching, and touching. Its themes are both very timely—the poor economy, the urge to downsize, the endless march of technology at the expense of traditional “people” jobs—and simultaneously timeless—do we need close relationships with other humans in order to flourish in our own lives? What does it mean to spend time with somebody, or to be intimate with them, if you believe that nothing will ever come of it? Its exploration of these themes is handled maturely, and yet it isn’t so self-serious that it becomes bogged down by them, making for a thoroughly entertaining film that has a few points to make along the way, and does so effectively.

Comments Off on Connecting Flight

The past couple of months have been unusually busy for me, as I’m sure my lack of writing output has indicated. Despite that, I’ve still been seeing movies—I just haven’t taken the time to write about my thoughts on them. In an effort to rectify the situation, here’s another bundled-together batch of movie reviews:

Where the Wild Things Are ( ) ) |

|

A Serious Man ( ) ) |

Whip It ( ) ) |

Fantastic Mr. Fox ( ) ) |

2012 ( ) ) |

A Christmas Carol ( ) ) |

Couples Retreat ( ) ) |

As opposed to how I usually do these (in order of release), this time they’re listed in order of how I would recommend them. Unfortunately some of these are no longer in theaters, but in those cases they should be available on video soon enough.

Where the Wild Things Are (

Where the Wild Things Are ( ) – Released theatrically 10/16/09; Directed by Spike Jonze; Written by Spike Jonze & Dave Eggers; Starring Max Records, James Gandolfini, Lauren Ambrose, Catherine O’Hara, Paul Dano, Forest Whitaker, Chris Cooper

) – Released theatrically 10/16/09; Directed by Spike Jonze; Written by Spike Jonze & Dave Eggers; Starring Max Records, James Gandolfini, Lauren Ambrose, Catherine O’Hara, Paul Dano, Forest Whitaker, Chris Cooper

So much more than a simple adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s timeless children’s book

, Spike Jonze’s live-action version of Where the Wild Things Are is an impressively bold film that goes places where few would dare, and succeeds in its unique vision from top to bottom. It’s the story of a boy named Max (Max Records) who has a typically tumultuous life for a boy his age, living with his single mother (Catherine Keener) and older sister (Pepita Emmerichs), neither of whom has enough time to keep him entertained. After a particularly bad fight with his mom, Max runs away and imagines himself escaping to a fantasy land where he is made king. There he meets the Wild Things, which should be held up as the gold standard of not only creature effects, but of voice acting as well. They’re part Henson Shop costumes, part CGI, with the line being blurred—and the appropriate restraint with animation being used—so as to make them come to life on screen as well as anything I’ve seen. The effect is amplified by exemplary voice acting, which is terrific throughout, but worthy of specific mention is the work of James Gandolfini and Lauren Ambrose, who bring a thoroughly impressive amount of life and depth to their Wild Things.

The overarching tale of this movie is a near-perfect realization of the mind of a child—the boundless imagination, the ad-hoc problem-solving skills, and the creative licenses that a young boy takes in telling himself a story within his own mind. This shouldn’t be too much of a surprise considering that co-writer Dave Eggers is the founder of 826 Valencia, a non-profit dedicated to nurturing children’s writing aspirations. (Eggers also wrote a novelization

to coincide with the film’s release.) Max often writes himself into a corner, only to invent new abilities or rules of the world in which his story takes place to get himself out of it. The way the Where the Wild Things Are script depicts aspects of Max’s real-world life as events and situations in the land of the Wild Things is particularly impressive; rather than overtly allegorical parallels, there’s more a translation of general emotions and relationships into subtly relevant imaginary situations.

The production is rounded out by some very unique music. The score, by the great Carter Burwell, is energetic and lively; it’s complemented (and often counterpointed) by hipster coffee-shop ditties by Karen O.. The former works better than the latter, but both conspire to establish the appropriate moods of the film throughout.

Upon first seeing Where the Wild Things Are, I thought its one downfall might be that it’s a bit violent for its target audience—there’s a lot of talk of stepping on heads, ripping out brains, and the like. I’ve been assured, though (by my preschool-teacher wife), that this is how kids play: it’s not real violence they’re imagining, it’s just creatively fertile minds being allowed to run wild; in fact, there’s a great example in the film of something that, realistically, should be a violent and gross situation, but filtered through the naive problem-solving mind of a child, it ends up being a tender, innocent moment. You’ll see what I mean. This is the kind of movie that grows on you, that you’ll enjoy continuing to reflect upon as much as you did sitting through it. Personally, I can’t wait to see it again.

A Serious Man (

A Serious Man ( ) – Released theatrically 10/2/09; Directed and written by Ethan Coen & Joel Coen; Starring Michael Stuhlbarg, Richard Kind, Fred Melamed, Sari Lennick, Aaron Wolff

) – Released theatrically 10/2/09; Directed and written by Ethan Coen & Joel Coen; Starring Michael Stuhlbarg, Richard Kind, Fred Melamed, Sari Lennick, Aaron Wolff

I saw an Ebert headline framing the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man as a retelling of the Book of Job (it was probably this review, but as per my standing rule of not reading other reviews of a movie until I’ve written my own, I haven’t read it yet). After seeing the movie for myself, in the most hallowed venue for the open exchange of ideas (the men’s room), I overheard a conversation reiterating that interpretation of it. Not being much of a Bible scholar myself, I’m not sure how adept the comparison is, but I do know that in general referring to a story as being “Job-like” means it’s about a guy who gets tested from every angle in his life and has a crisis of faith as a result, and that description certainly fits A Serious Man. Larry Gopnik, its main character (Micahel Stuhlbarg), has it coming at him from all sides: his wife (Sari Lennick) is leaving him for a mutual friend named Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed); his brother Arthur (Richard Kind) is overstaying his welcome in the Gopnik home, and is drawing the attention of the FBI via a quack numerology scam he uses to help him achieve gambling success; his son Danny (Aaron Wolff) is getting himself into trouble at school; one of his students at the college where he teaches physics is accusing him (falsely) of capricious grading; and his neighbors at home are causing uncomfortable situations for him, to say the least.

Larry frequently wonders what could possibly be Hashem‘s intention in all of this, and so he seeks advice from a series of three Rabbis. It should go without saying that these interactions are open to a variety of interpretations, but my reading of them is not only as a humorous commentary on the role of traditional religion in people’s lives, but as an outright indictment of its futility in addressing real-world problems. These Larry-Rabbi meetings frame the structure of the film, and they serve as its comedic high points as well. (They’re also tied to a Jefferson Airplane motif that runs throughout the film, which I particularly enjoyed.)

Like all of the Coen Brothers’ best work, this is meticulous filmmaking. To those who enjoy the well-crafted set-up of a scene, the slow build of subtle storytelling, the ability of a film to frustrate an audience with an impressively strong sense of empathy for its characters, it’s a must-see; A Serious Man is the product of accomplished artists at the top of their craft. For others, though, it will feel too drawn out, too modestly scoped, and too open-ended (as I mentioned, it’s open to a lot of interpretation, and is happy to leave you to engage in that interpretation on your own, rather than pointing you in a specific direction or explicitly spelling things out). I count myself more in the former camp than the latter, but I do admit that I felt the movie dragged at times. Stylistically, it’s as polished and finely-crafted as No Country For Old Men, but slower, smaller, and more personal in its approach. (Also like that film, it credits Carter Burwell with a score, though I have no recollection of there being one.) It has a lot in common with Fargo, but it’s not as funny, and not as light-hearted in its tack. It has a prologue sequence of confusing relation to the rest of the film. It ends abruptly in a way that will either frustrate or satisfy, depending on your disposition (personally, I loved it). It’s a slice-of-life story filtered through the minds of the Coens, who operate at a level above just about everyone else out there, and that in and of itself is enough to recommend it.

Whip It (

Whip It ( ) – Released theatrically 10/2/09; Available on DVD

) – Released theatrically 10/2/09; Available on DVDand Blu-ray

1/26/10; Directed by Drew Barrymore; Written by Shauna Cross; Starring Ellen Page, Alia Shawkat, Marcia Gay Harden, Daniel Stern, Kristen Wiig

There’s a genre of film that sets itself in the world of a niche pasttime, teaching its audience about that world while telling its story. Whip It, the directorial debut of Drew Barrymore, is such a film. It’s the story of a girl named Bliss (Ellen Page) who is disenchanted with the beauty pageants her southern mother (Marcia Gay Harden) has forced her into since she was a young girl. She seeks out a more exciting and fulfilling source of thrills, as angsty teenagers in movies tend to do, and finds herself in a Texas roller derby league. The audience learns about the sport along with her, as Bliss—you guessed it—grows up a bit in the process, earning the respect of her parents and even managing to fall in love while she’s at it.

The story itself is a cliche, but it has the unique aspect of the roller derby league to fall back upon for bouts of originality. Barrymore does an impressive job of directing, in several respects. Her style for bringing us up to speed on the world of roller derby is fresh and nicely handled: the rink announcer (Jimmy Fallon) describes the rules to the crowd while narrating the action, which Barrymore intercuts with cute diagrams showing the “strategy” behind the sport. The action overall is shot tastefully, keeping things exciting and tense without resorting to rapidfire cuts and shaky camera work, as is all too common as of late. The script, written by Shauna Cross and based on her book

, knows its structure isn’t all that unique, but it adds a lot of originality in how it handles the details. It has fun with the names of the derby girls: Barrymore appears as “Smashley Simpson,” Kristen Wiig is “Maggie Mayhem,” the always fun to see Zoe Bell (who I fell in love with when she played herself in Death Proof) shows up as “Bloody Holly.” Et cetera. There’s even a couple of derby-ers called the “Manson Sisters”—an obvious homage to Slap Shot. It’s all tongue in cheek and self-knowingly cute, but the tone works well enough in context.

The story draws some additional depth from Bliss’s relationship with her parents, who are extremely well-written. Daniel Stern, in particular, is a likeable yet realistic father, and he plays his role truthfully and lovingly. He’s like a toned-down version of J.K. Simmons’ dad from Juno, with as many wisecracks but more emotional relevance. The counterpoint lies in Bliss’s relationship with Oliver (Landon Pigg), which is weakly developed and sort of nonsensical (Pigg’s ho-hum acting doesn’t help much, either). Despite that, Whip It is a fun film that’s executed better than most in this genre. It’d be tempting to call it “Dodgeball for girls,” but it’s more—and better—than that.

Fantastic Mr. Fox (

Fantastic Mr. Fox ( ) – Released theatrically 11/25/09; Directed by Wes Anderson; Written by Wes Anderson & Noah Baumbach; Starring George Clooney, Meryl Streep, Jason Schwartzman, Eric Anderson, Wally Wolodarsky, Bill Murray

) – Released theatrically 11/25/09; Directed by Wes Anderson; Written by Wes Anderson & Noah Baumbach; Starring George Clooney, Meryl Streep, Jason Schwartzman, Eric Anderson, Wally Wolodarsky, Bill Murray

Like most movie nerds, I’m a pretty big Wes Anderson fan, so I was looking forward to seeing his treatment of Roald Dahl’s children’s book

Fantastic Mr. Fox. Expecting it to be “A Wes Anderson Movie,” I think, is why I ended up being slightly disappointed in it: there are a few Anderson-style touches here and there—his trademark titles, a hip musical number—but on the whole, the movie is a straight-up kids’ film. This isn’t to say it’s not good—it is. It just doesn’t really go above and beyond being a movie geared towards children, especially when Where the Wild Things Are is still fresh in my mind. Like that film, it features great voice acting, particularly from its two leads (George Clooney and Meryl Streep), with Anderson regulars (Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Owen Wilson) rounding things out nicely.

The stop-motion animation of the film has a bit of a retro feel to it, which fits with Anderson’s sensibilities quite well. The tone of Fantastic Mr. Fox is informed by its style of animation, with things remaining light-hearted and fun throughout. The writing style is playful, as well. The characters cuss at each other in the most literal fashion (they know just one obscenity: “cuss”). They’re happy to refer to each other as wild animals, and are surprisingly educated on the Latin names for each others’ species. The world in which they exist is one of malleable rules; for example, sometimes it seems like the humans cannot understand what the animals are saying, while at others they clearly can.

The story is essentially Chicken Run in reverse. The titular Mr. Fox (Clooney) gives up his life as a professional chicken-stealer in order to raise a family, but he misses the rush of his former job and gets himself into a mess of trouble by surreptitiously returning to it, against the wishes of his wife (Streep). He’s aided by his possum landlord (Wally Wolodarsky), his hapless son (Schwartzman), and his athletic wunderkind of a nephew (Eric Anderson). What follows is a fairly standard critters-versus-farmers battle of wits, which progresses into a battle of arms as well, as the rest of the community of animals also gets involved in the struggle (including Bill Murray’s badger lawyer and his family). Along the way, they combat a conglomerate of three farmers, who are aided by their drunken rat security guard (Willem Dafoe). Things remain light throughout, but Mr. Fox does take the time to reflect on his life and his responsibilities to his family and his community at times, fulfilling the requisite moral subtext. There’s nothing really groundbreaking in Fantastic Mr. Fox, but it’s enjoyable nonetheless, and Wes Anderson’s stylistic touches keep things fun and interesting. I imagine that kids would find it even more entertaining than I did.

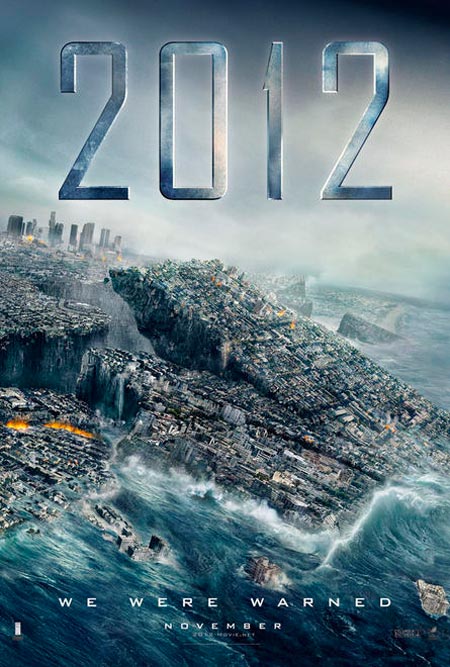

2012 (

2012 ( ) – Released theatrically 11/13/09; Directed by Roland Emmerich; Written by Roland Emmerich & Harold Kloser; Starring John Cusack, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Oliver Platt, Amanda Peet, Danny Glover

) – Released theatrically 11/13/09; Directed by Roland Emmerich; Written by Roland Emmerich & Harold Kloser; Starring John Cusack, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Oliver Platt, Amanda Peet, Danny Glover

With the Y2K nonsense well behind us, the next doomsday scenario for the paranoid to obsess over is the 2012 “prediction” of the Mayan calendar, which supposedly foretells the end of the world in December of that year. It was inevitable that Hollywood would take a crack at this story (and I’m sure there’ll be more than one), and I suppose if it was going to be done, Roland Emmerich is as good a choice as anybody to be the one to do it. He relishes in big films, with big stars, big effects, big explosions, and big stakes, and his 2012 is all of that. It’s also big in running length, which is probably its biggest downfall; a movie like this can be fun for about 90 minutes, but add another hour onto that and it just drags, whatever charm it had wearing off rather quickly.

Emmerich has assembled for this film a fantastic cast, full of great actors who dive deep into their roles and help the film maintain credibility, despite its otherwise-silly premise. I would call John Cusack and Chiwetel Ejiofor co-leads; the former is the audience’s surrogate who goes through the adventure of the “end of the world as we know it” as an everyday man (albeit one with exceptional driving skills), and the latter is the scientist who provides the necessary explanation of what is happening (it has something to do with some hand-waving about the sun emitting too many neutrinos and causing the earth’s crust to shift in catastrophic ways). The decimation of the planet comes quickly and often, and for the first half of the movie it is the primary focus. The world-destruction special effects are really good, although a little curious at times: as earthquakes spread throughout LA, the ground doesn’t so much break apart as just dissolve, while Cusack drives his limo just inches ahead of the opening chasms (which reminded me a bit of Angela Bassett’s character from Strange Days, but with the absurdity turned up to 11—he jumps a hole in the ground not once, but twice). To me one of the most fun parts of a disaster movie is seeing the destruction of iconographic structures, and 2012 is happy to indulge in that particular cliche: the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio crumbles, the Wynn in Las Vegas sinks into the ground, the skyscrapers of downtown LA tilt and crash into each other, and all of this is done exceptionally well, with some of the best CG effects to date.

There’s also some interesting conspiracy-theory takes on the goings-on, with the governments of the world knowing about the forthcoming devastation but not making it public knowledge. Danny Glover makes a great President of the U.S., and plays his role with dignity, while Oliver Platt is a stereotypical (but effective) douchebag advisor who lets his ego get in the way of his judgment. On the other end of the spectrum is a humorous Woody Harrelson as the crazy off-the-gridder who has so many whacky theories that one of them is bound to be right. There are other stereotypes as well: Cusack’s character, of course, is a down-and-out novelist with family problems (his ex-wife, played by Amanda Peet, has remarried, his kids prefer their new father-in-law, etc.). He becomes, of course, the unlikely hero. There’s also a tacked-on love story with Ejiofor and Thandie Newton, who, like the rest of the cast, gives a good performance (redeeming herself, in my mind at least, for W.). Really, there are just too many characters, too many side-plots, which simply serve to bog down the storyline and extend the movie’s running time. It feels like Emmerich and his co-writer Harold Kloser started by listing every cliche they could think of, and then making sure they worked them all into their script—with an extra helping of cheese on top. It’s fun for a while, but 2012 isn’t able to sustain the momentum of its first and second acts throughout its all-too-long third. I think the best advice I could give to somebody who might be interested in seeing this film, in fact, is to see Knowing instead.

A Christmas Carol (

A Christmas Carol ( ) – Released theatrically 11/6/09; Directed and written by Robert Zemeckis; Starring Jim Carrey, Gary Oldman, Colin Firth, Cary Elwes

) – Released theatrically 11/6/09; Directed and written by Robert Zemeckis; Starring Jim Carrey, Gary Oldman, Colin Firth, Cary Elwes

Every time I’ve encountered an incarnation of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, I find myself sympathizing with Ebenezer Scrooge during the early stages of the story, which I suppose says something about my predisposition to the classic tale. Robert Zemeckis’s recent motion-captured, computer-animated adaptation was no different. To the best of my knowledge, it is the most literal film version of A Christmas Carol, following the original story very closely, but also remaining true to the Dickensian language of the book and the moods and emotions it originally intended to invoke. (Todd Alcott wrote a nice piece about how Zemeckis gets the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come as well as anybody.)

When it comes down to it, I suppose, A Christmas Carol is not a story I feel a particular affinity for, and I’m sure a significant portion of the reason for that is overexposure. Due to this fact, a new adaptation of it really has to go above and beyond in order to stand out, and Zemeckis does achieve this in some ways, but misses in more. Most of what it is successful at comes from Jim Carrey, who voices and provides the motion-capture acting for not only Scrooge—at multiple stages of life—but also all three of the ghosts he encounters, as well. The rest of the cast, however, tends to be overly melodramatic, with Zemeckis’s script as much to blame as his direction in this regard. Even the great Gary Oldman uncharacteristically over-acts a bit, which might be the film’s largest disappointment.

The animation, from Zemeckis’s ImageMovers Digital studio, is frustratingly uneven. Extra detail is afforded to the main characters (those portrayed by Carrey, and Oldman’s Bob Cratchit), who look nearly photo-realistic. The lesser characters, however, aren’t modeled with as much detail, and the end result is that it looks like Carrey’s characters are interacting with animatronic mannequins rather than other human characters. I understand the reasons for this—the more detailed the models, the longer the film takes to render—but it’s a poor production choice to make. It ends up making the film feel like it was rushed out the door in order to hit a specific release date (which is obviously desirable in this case) at the expense of its visuals: it’s going more for box office success than craft, and that’s always a formula for mediocrity. Likewise, the biggest departure from the classic tale in this incarnation is a silly sequence involving a shrunken Scrooge sliding around on what amounts to an amusement park ride made out of ice, in a blatant instance of setting the story aside for a while in order to make sure audiences who paid extra to see the film in 3D (which I did not do) feel like they got their money’s worth.

While parts of this most recent iteration of A Christmas Carol are impressive—Jim Carrey’s voice work, some of the character animation (particularly Scrooge), and the close adherence to the source material—it is mostly marked by a lack of uniqueness and creativity. With so many other adaptations already in existence, this one ends up being more of a proof-of-concept for Robert Zemeckis’s obsession with motion-capture animation technology, rather than a novel and original film that’s able to stand on its own.

Couples Retreat (

Couples Retreat ( ) – Released theatrically 10/9/09; Directed by Peter Billingsley; Written by Jon Favreau and Vince Vaughn & Dana Fox; Starring Vince Vaughn, Jason Bateman, Jon Favreau, Malin Akerman, Kristin Bell, Kristin Davis

) – Released theatrically 10/9/09; Directed by Peter Billingsley; Written by Jon Favreau and Vince Vaughn & Dana Fox; Starring Vince Vaughn, Jason Bateman, Jon Favreau, Malin Akerman, Kristin Bell, Kristin Davis

Couples Retreat is another in the long line of half-assed comedies, where the thinnest excuse for a story is thrown together so that some friends who happen to be actors can get together and have fun for a couple of months, and call the result a movie. It’s billed as starring Vince Vaughn, who seems to be happy to completely phone in the majority of his roles lately, despite the fact that he’s capable of being a fine actor when he actually tries. It’s really an ensemble cast, though, presumably because none of the actors involved wanted to work more than one-eighth of the time they would if asked to carry a film on their own. The most curious among the rest of the cast is Jason Bateman, who’s had a string of impressive—and credible—roles over the past few years, and even here seems like he’s the only one trying to keep things legitimate… which makes him feel quite a bit out of place. (Perhaps even more disappointing, though, is A.R. Rahman doing the film’s music; it’s sad to think that this was the highest-profile offer he got after his Oscar-winning score for Slumdog Millionaire.)

While I usually am pretty critical of movies with an ill-conceived storyline, Couples Retreat is one case where I find myself wondering why they even bothered. You can look at the poster and know exactly what it’s going to be about, so the exposition, no matter how protracted it may be, just serves to start things off on a boring note. And then after the jokes dry up, and all of the whacky occurrences that could be conceived to happen at an island resort have come to pass (hint: most of them involve instances of mistaken sexual identity), then there’s an attempt at a real story shoehorned in, which somehow makes things even worse. This is the answer to the typical comedy that wraps things up all too nicely in the last 5 minutes: here it’s a good 45 minutes of resolutions and lessons learned, and it’s even more boring than the exposition.

The climactic scene may be my least favorite of all. I’ve written before about my feelings on the Guitar Hero-type games, and while I think they’re silly, I admit that they’re also mostly harmless, but what I find even dumber than playing those games is watching others play them. And now I’ve found an additional level of dumb: paying money to watch a movie in which you have to watch other people pretend to play a game about pretending to play an instrument. In this case it’s a guitar-off between Vaughn—whose character is somehow involved in the business (apparently there’s a “business” of Guitar Hero)—and his nemesis, the resort director named Sctanley (isn’t it hilarious how his name is spelled with a c?).

This isn’t to say that there’s nothing funny in Couples Retreat, but there certainly isn’t a ton. As The Onion so accurately pointed out, it’s hard to believe that even the stars involved thought that what they were making was actually humorous or enjoyable.