I’ve got a couple of catch-up reviews to get to, but before doing so I wanted to revisit a couple of the thoughts I’d previously posted on Christopher Nolan’s Inception, in light of some insights I’ve gained from reading the shooting script.

- I’d mentioned, in my confusion of how the dreams work, that Arthur tells Saito it’s his second-level dream they’re in. Arthur is shot, and yet the dream continues. This seems to have been a case of me incorrectly recalling the specifics of what was going on; in the script, it’s actually Nash who tells Saito they’re in his dream. This makes more sense, of course, as it is Nash who screwed up the detail of the carpet, and subsequently gets punished for it.

- I was also unclear as to how the roles of dreamer and architect work and interact with each other. In fact, during the planning stages of the mission, Nolan mentions on two separate occasions that Ariadne is showing the details of her design to the dreamers in the background, while Cobb is explaining the mission in the foreground. The first instance is in New York (Yusuf’s dream):

EXT. NEW YORK STREETS—DAY The team are in the middle of a DESERTED intersection. Ariadne is showing Yusuf aspects of the geography. EAMES We could split the idea into emotional triggers, and use one on each level.

And the second is in the hotel (Arthur’s dream):

INT. DESERTED HOTEL LOBBY—DAY The team sit on the steps of the large marble lobby, debating. Ariadne is showing Arthur the lobby.

This was either lost in editing, or it was so subtle in the finished film that I completely missed it, but it does explain a bit, and fills in a gap that was annoying me. (Now the only thing that annoys me about the above is how Nolan, a Brit, uses collective nouns: “The team are…”)

- I agreed with an opinion piece I’d referenced that the bizarre narrow alleyway in Mombasa may have been the clearest sign that the entire movie occurs within Cobb’s dream. While Nolan doesn’t spell it out explicitly in his screenplay, he does describe the way the crowds look at Cobb as he runs through the streets of Mombasa in the same manner he describes the “projections” looking at Ariadne during her dream-tutorial. On the folded streets of Paris:

As they walk, Ariadne notices more and more of the projections STARING at her.

Then on the bridge:

People crossing the bridge STARE at Ariadne. Several of them BUMP her shoulder as they pass.

And finally:

Cobb says nothing. He stands there, staring at Ariadne. PEOPLE around her stop and look at her, hostile. COBB Look, this isn't about me— Cobb reaches for Ariadne's arm, turns her to him– ARIADNE Is that why you need me to build your dreams? A passerby GRABS Ariadne's shoulder– COBB Leave her alone— More of the crowd join in, PULLING at Ariadne, holding her arms open– Cobb PULLS people off– the crowd PUSHES him away–

By comparison, when Cobb escapes from the cafe in Mombasa:

Cobb stands up, PUSHES into the crowd– faces PEER at him– he moves, trying to blend– a SECOND BUSINESSMAN is there.

And finally, when Cobb finds the alleyway:

Cobb LOOKS left, right... CUTS LEFT into a narrow, CROWDED alley– the alley NARROWS TO A DEAD END. Faces in the CROWD start to watch Cobb– PEOPLE start to SURROUND him– Cobb looks back the way he came– the two Businessmen are there, GUNS DRAWN–

Maybe I’m looking too hard at this, but to me both sequences have the same tone of writing. Particularly in Mombasa, it seems Nolan is going to great lengths to draw attention in his script to the behavior of the crowds, which is the same as the behavior of projections that “feel the foreign nature of the dreamer” and attack “like white blood cells fighting an infection.”

- The line I couldn’t catch that Arthur mumbles after losing a guard on the Penrose stairs is, “Paradox.”

- Perhaps the most telling thing I learned from reading the Inception shooting script comes from the introduction, which consists of an interview of Christopher Nolan by his brother (and sometimes collaborator) Jonathan. Nolan says:

I was definitely looking for a reason to impose rules in the story during the writing process. When I saw the first Matrix film, I thought it was really terrific, but I wasn’t sure I quite understood the limits on the powers of the characters who had become self-aware.

I find it odd that Nolan contrasts his film with The Matrix and thinks that he has provided a more clear explanation of how his world works than the Wachowski brothers did. The only conclusion I can come to from this is that Nolan must actually have all of the specifics of how the world of Inception works straight in his mind, but he just wasn’t able to adequately convey that clarity on the page or in the completed film. It’s interesting to me that he chooses the same influence myself and others have compared his movie to, but arrives at the completely opposite conclusion. Obviously he’s biased, and like I said, it probably all makes sense to him, but what’s weird is that he thinks The Matrix—which I consider to contain one of the best expository introductions to a fantasy world ever put to film—actually doesn’t do a good job of explaining itself.

So I don’t know that this will be the last I have to say about Inception, but I’m glad to have been able to clear up some of my own confusion, and also to solidify some of the conclusions I’d drawn from my own analysis of the film. I’ve always been a big fan of using screenplays to help gain additional understanding of a movie, especially when the movie in question was written by the director. Check out Inception: The Shooting Script if you have the same interest.

In my review of Christopher Nolan’s Inception, I mentioned that I find it to be a frustrating film. Among many other reasons (which I’ll get into more below), the basic source of this frustration for me is that the movie feels like it could be more than it is (and, indeed, probably should be), but also that Nolan clearly already thinks that’s the case. He makes movies that are imbued with a permeating sense of self-importance, and for me this not only holds them back, but also serves to make clear the sense of what could have been, while also adding some unneeded (and unwanted) pretension on top.

It doesn’t help that Nolan is the Internet’s darling these days, making it hard to cut through all of the hyperbole when trying to research what other people think of the movie. For instance, I went to read this review on CHUD—by a talented writer who does some of the best online movie reviews you’ll find, and for whom I have a lot of respect—but I had a hard time getting past the first sentence (I did eventually read the whole review, and it’s much more measured and well-thought-out than that first sentence initially led me to believe). I think that A.O. Scott hit it on the head when he said, “I think it used to be that ‘masterpiece’ was the last word, the end of the discussion, rather than the starting point.” But in this case, it seems, that declaration was made by many before even seeing the film in the first place.

It doesn’t help that Nolan is the Internet’s darling these days, making it hard to cut through all of the hyperbole when trying to research what other people think of the movie. For instance, I went to read this review on CHUD—by a talented writer who does some of the best online movie reviews you’ll find, and for whom I have a lot of respect—but I had a hard time getting past the first sentence (I did eventually read the whole review, and it’s much more measured and well-thought-out than that first sentence initially led me to believe). I think that A.O. Scott hit it on the head when he said, “I think it used to be that ‘masterpiece’ was the last word, the end of the discussion, rather than the starting point.” But in this case, it seems, that declaration was made by many before even seeing the film in the first place.

At any rate, there are a few issues I had with Inception—and some aspects I really appreciated—which I touched on in my review but didn’t go into in deference to my general no-spoilers rule of reviews. I’d like to take a bit of a deeper look at some of those key elements of the film here, and this time we’ll get into the details, spoilers and all.

1. Mechanics

It seems quite clear to me that Christopher Nolan is a pretty lazy and sloppy writer. He has good ideas, and they make for exciting cinema, but he’s not willing to do the work and go to the trouble of actually fleshing them all out in a totally cohesive manner. Most people seem comfortable with the mythology of Inception, and while it holds up enough to keep the movie speeding along at its non-stop breakneck pace, I think it’s pretty clear that upon a little more reflection there are some serious holes.

The film’s opening scene serves as a whirlwind introduction to the would-be science of how the dream-invasions—and the film itself—function. We learn about Extraction, the dream-stealing business in which Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio), Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), and the rest are involved.  We see Mal (Marion Cotillard) early on, and it is immediately shown (rather than explained—a rare case for Nolan) that she is an uncontrollable force in the world of dreams (though we don’t yet know the specifics). We learn how Nolan’s notion of the human mind works, specifically with regards to how secrets are stored and are able to be extracted (a clever concept that, it’s been pointed out, is anything but unique). And we’re taught, by means of explanation to Saito (Ken Watanabe), of the concept of dreams-within-dreams, which of course will become quite important about an hour from now.

We see Mal (Marion Cotillard) early on, and it is immediately shown (rather than explained—a rare case for Nolan) that she is an uncontrollable force in the world of dreams (though we don’t yet know the specifics). We learn how Nolan’s notion of the human mind works, specifically with regards to how secrets are stored and are able to be extracted (a clever concept that, it’s been pointed out, is anything but unique). And we’re taught, by means of explanation to Saito (Ken Watanabe), of the concept of dreams-within-dreams, which of course will become quite important about an hour from now.

Arthur tells Saito that this initial 2nd-level dream is his, and when things get hairy, the solution is to shoot Arthur to wake him up. And yet, when that happens, the dream continues. This is but the first in what will become an annoyingly long string of incompletely-worked-out mechanics in Inception. (It’s possible that Arthur was lying when he told Saito they were in his dream, but I’m not sure what purpose that would serve.)

When Ariadne (Ellen Page) is brought in to replace Nash (Lukas Haas) as the dream architect for the team’s upcoming mission, it’s a cheap way for Nolan to explain how everything works to the audience. Ariadne serves to ask the questions that we want answered, but the details she gets from Cobb don’t add up very cohesively. We’re told that what the team does is to insert themselves into the subconscious of the subject, which is somehow inside the dream of a third party. None of this really makes much sense, but it’s obvious that Nolan’s intention is for us to just buy Cobb’s glossing-over explanations and go along with it. The architect’s role, in particular, seems very arbitrary; we know that the architect need not be present in the dream, because later when the mission commences Ariadne has to talk her way into going along on it. We never see how the architect’s designed dreamscape gets into the dream in the first place, except we know that the dreamer can add his or her own architectural aspects if needed, because Eames (Tom Hardy) does so in his snowy fortress-assault dream (more on this in a bit).

When Ariadne (Ellen Page) is brought in to replace Nash (Lukas Haas) as the dream architect for the team’s upcoming mission, it’s a cheap way for Nolan to explain how everything works to the audience. Ariadne serves to ask the questions that we want answered, but the details she gets from Cobb don’t add up very cohesively. We’re told that what the team does is to insert themselves into the subconscious of the subject, which is somehow inside the dream of a third party. None of this really makes much sense, but it’s obvious that Nolan’s intention is for us to just buy Cobb’s glossing-over explanations and go along with it. The architect’s role, in particular, seems very arbitrary; we know that the architect need not be present in the dream, because later when the mission commences Ariadne has to talk her way into going along on it. We never see how the architect’s designed dreamscape gets into the dream in the first place, except we know that the dreamer can add his or her own architectural aspects if needed, because Eames (Tom Hardy) does so in his snowy fortress-assault dream (more on this in a bit).

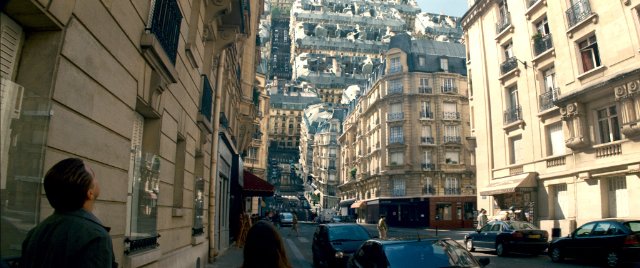

What’s most disappointing about the learning/mechanics sequence, though, is that we are shown some awesome effects that can be achieved—the exploding cafe, the folding streets, the mirrored corridor, the Penrose stairs—but rather than being a setup for even more awesome tricks to come later, these exist in the film purely for the visual thrill they provide as a way to spice up an otherwise drawn-out expository sequence. The only one of these tricks that comes up at all in the rest of the film is the Escher-like staircase effect, which Arthur uses to evade a bad guy in the hotel dream. And this further begs the question of how this all works: did Ariadne put those stairs in the hotel, for Arthur to make use of if needed, or was he able to call upon them only when the situation arose? (After the bad guy Arthur is trying to get away from falls down the stairwell, he mumbles something that was unintelligible to me in two viewings, but for all I know it might be along the lines of “Thanks, Ariadne.”)

What’s most disappointing about the learning/mechanics sequence, though, is that we are shown some awesome effects that can be achieved—the exploding cafe, the folding streets, the mirrored corridor, the Penrose stairs—but rather than being a setup for even more awesome tricks to come later, these exist in the film purely for the visual thrill they provide as a way to spice up an otherwise drawn-out expository sequence. The only one of these tricks that comes up at all in the rest of the film is the Escher-like staircase effect, which Arthur uses to evade a bad guy in the hotel dream. And this further begs the question of how this all works: did Ariadne put those stairs in the hotel, for Arthur to make use of if needed, or was he able to call upon them only when the situation arose? (After the bad guy Arthur is trying to get away from falls down the stairwell, he mumbles something that was unintelligible to me in two viewings, but for all I know it might be along the lines of “Thanks, Ariadne.”)  At any rate, whether the architect has put these stairs in place ahead of time or whether the dreamer can summon the effect at will, neither situation really clarifies what’s going on—if Arthur is able to control the environment of his own dream in such ways, what’s the need of the architect in the first place?

At any rate, whether the architect has put these stairs in place ahead of time or whether the dreamer can summon the effect at will, neither situation really clarifies what’s going on—if Arthur is able to control the environment of his own dream in such ways, what’s the need of the architect in the first place?

My point here is not just to point out how incompletely explained the mechanics of the film are; my point is that I feel pretty confidently that Christopher Nolan himself has not worked out these details. His film is comprised of half-developed concepts that make for exciting and “complex” cinema, but they’re not fleshed out to an extent that holds up to the kind of scrutiny a film like this almost demands. (It’s worth noting that the marketing scheme for Inception has now gone into “You need to see it more than once!” territory.) I realize that I am bothered by such things more than most, but to me a good film—especially one that is going to be deemed “a masterpiece”—needs to have this level of cohesion; it needs an air-tight script, and that is simply not the case here.

2. Characters

One of the biggest tell-tale signs of lazy writing is the fact that in an ensemble cast, there are precisely two characters with any kind of backstory or actually developed characterization whatsoever. They are Fischer (Cillian Murphy, who gives a really great performance, particularly at the film’s climax), and Cobb, whose story it is that we’ve ostensibly come to watch. The rest of the characters exist not to be representations of people, with real emotions and problems and goals, but simply to fill roles, to be types. I’ve already mentioned Ariadne, whose purpose in the movie is twofold: she asks Cobb for the explanations that we as an audience require in order to be able to follow along, and she reminds Cobb (and us)—repeatedly—of the function of Mal.  It seems to me that about 50% of her dialogue is some variation of the line, “Cobb, you can’t control Mal and we don’t know what she’ll do! She’s dangerous!” I find Ellen Page’s performance to be exceptionally dull, too; she sticks out like a sore thumb in what is otherwise a pretty solid cast as the one person who’s not putting their heart and soul into it. This is likely at least partially a result of her character’s function: she’s not really much of a character at all, she’s just there because Nolan thinks we’re all drooling, popcorn-inhaling idiots who wouldn’t be able to keep things straight without her. (And who the hell is named Ariadne, anyway? I know it’s a reference to a labyrinth-foiler from Greek mythology, but who actually gives their kid that name? It’s like Nolan just Googled some shit about labyrinths while writing the script and used the first thing he found.)

It seems to me that about 50% of her dialogue is some variation of the line, “Cobb, you can’t control Mal and we don’t know what she’ll do! She’s dangerous!” I find Ellen Page’s performance to be exceptionally dull, too; she sticks out like a sore thumb in what is otherwise a pretty solid cast as the one person who’s not putting their heart and soul into it. This is likely at least partially a result of her character’s function: she’s not really much of a character at all, she’s just there because Nolan thinks we’re all drooling, popcorn-inhaling idiots who wouldn’t be able to keep things straight without her. (And who the hell is named Ariadne, anyway? I know it’s a reference to a labyrinth-foiler from Greek mythology, but who actually gives their kid that name? It’s like Nolan just Googled some shit about labyrinths while writing the script and used the first thing he found.)

Everybody else in the cast is exclusively one-dimensional. There’s been a lot written about Inception as a metaphor for film production itself (probably the best of these that I’ve read is this one—by the same writer, Devin Faraci, who wrote the review I referenced earlier). But no matter how you look at the roles of the supporting cast, you’re not going to find much depth there. The team-building sequence in the movie is familiar from any heist flick, except that Nolan doesn’t bother telling you much of anything about who these people are; they exist to fill a role, and that’s it.  Of the supporting cast members of the dream team, I think that Tom Hardy stands out as Eames; he’s the benefactor of the movie’s lone attempts at humor. Joseph Gordon-Levitt tries too hard to be a badass as Arthur (his forced-deep voice makes it impossible for me to take his character very seriously), and poor Dileep Rao seems like he’ll spend his whole career being cast as a mystical-Eastern-guy stereotype (his Yusuf is not very unlike the character he played in Drag Me to Hell, with a little of his Avatar scientist blended in).

Of the supporting cast members of the dream team, I think that Tom Hardy stands out as Eames; he’s the benefactor of the movie’s lone attempts at humor. Joseph Gordon-Levitt tries too hard to be a badass as Arthur (his forced-deep voice makes it impossible for me to take his character very seriously), and poor Dileep Rao seems like he’ll spend his whole career being cast as a mystical-Eastern-guy stereotype (his Yusuf is not very unlike the character he played in Drag Me to Hell, with a little of his Avatar scientist blended in).

Compounding the confusion of the film—or at least adding to the amount of effort that’s required to follow it—is the inconsistent pronunciation of some of these characters’ names. Sometimes Yusuf is YOO-sef, sometimes he’s yeh-SOOF. (Arthur refers to him using the latter pronunciation at a key point in the hotel dream, and I didn’t catch what he was referring to until my second time seeing the film.) There is only one instance where I’ll excuse a movie for such sloppiness, and that’s in the Star Wars movies, where Lando pronounces “Han” and “Leia” differently than everybody else. But that’s excusable because it’s Billy Dee Williams, and who’s going to correct Billy Dee Williams?

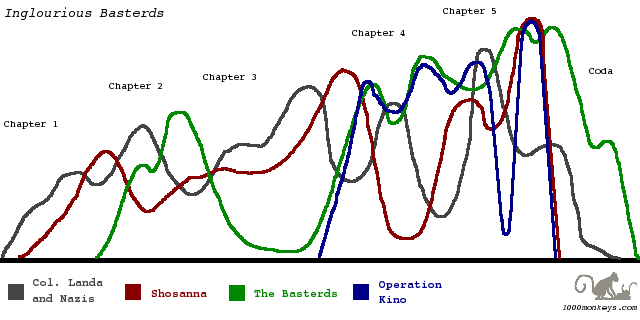

3. Video Games

Another frequent commentary on Inception is that it feels, and plays out, like a video game movie that just so happens to not actually be based on a video game. This is usually presented as a positive, but I’m not sure why. To me, it’s a “video game movie” because it’s structured in terms of “levels,” with each getting progressively more difficult for the heroes to navigate. These levels are populated by unnamed, usually faceless foot soldiers, who are easily dispatched and only serve to slow down the progression to the level’s ultimate goal—and to keep the film dense with action scenes. There’s a good visual representation of how the levels stack here, but the one thing I’d add is that each level even features a “boss,” a character that is harder to get past than the other sentries have been, and who guards the level’s final objective.

- In level 2 (the Van Chase), after plowing through bad guys with relative ease, Yusuf must fight through a Big Black SUV that gives him more trouble on the bridge. This SUV is his last obstacle before being able to drive through the guardrail and into the water.

- In level 3 (the Hotel), there is one guard who gives Arthur more trouble than the rest. He is finally able to evade this guard by using the Penrose steps trick in a stairwell.

In level 4 (the Snow Fortress—the most video game-like part of the film), the final boss is Mal, who shows up just before the goal has seemingly been reached. Cobb must shoot her to clear the way for Fischer to enter the vault and confront his father.

In level 4 (the Snow Fortress—the most video game-like part of the film), the final boss is Mal, who shows up just before the goal has seemingly been reached. Cobb must shoot her to clear the way for Fischer to enter the vault and confront his father.- In level 5 (Limbo), things become sort of a clusterfuck. The “boss” here is again Mal, who seems to have more power this time around—a common video game trope.

The most insightful piece I’ve read about Inception-as-video-game is Inception‘s Usability Problem, which explores the film’s exposition as a tutorial in how to watch it. I particularly enjoyed the comparison that article makes to The Matrix, an obvious inspiration for this film that serves as a telling example of how such things are handled by far better screenwriters than Nolan.

4. Performing Inception

Inception goes to great lengths to ensure that we understand the importance of the “kicks” that serve to wake the characters from the various levels of dreams. The 4-way kick sequence, from the time Yusuf drives the van off the bridge, to the time it hits the water, and everybody awakens from the multiple levels of dreams simultaneously, occupies a full 30 minutes of screen time. It’s a virtuoso example of cross-cutting and sustained tension. (Most impressive may be the fact that although the ever-falling van evokes the old cliche of a slowly-closing overhead door that seems to backtrack a bit every time we cut to it, Nolan never falls into this suspension of disbelief-killing trap.)

As the film races towards its climax, however, Nolan throws his own rules by the wayside. In the snow fortress level, when time becomes of the essence, a shortcut appears out of nowhere to save the day. (“Did Eames add any shortcuts?” Cobb asks Ariadne. Why, how fortunate, it just so happens that he did!) Nolan seems to have a knack for writing himself into a corner, and then pulling something out of his ass to gloss over the would-be problem and keep the action barreling forward. The worst such instance is the business with the kicks; towards the end of the half-hour-long, synchronized 4-way kick sequence, we find Cobb and Saito still down in Limbo. We know that this is a tenuous situation because Nolan has gone out of his way to warn us, over and over, about how people can get stuck “down there.” And yet, how do Cobb and Saito come out of it? It’s not shown, but we can infer that they simply shoot themselves (the last image in Limbo we see is old-Saito reaching for a gun).

As the film races towards its climax, however, Nolan throws his own rules by the wayside. In the snow fortress level, when time becomes of the essence, a shortcut appears out of nowhere to save the day. (“Did Eames add any shortcuts?” Cobb asks Ariadne. Why, how fortunate, it just so happens that he did!) Nolan seems to have a knack for writing himself into a corner, and then pulling something out of his ass to gloss over the would-be problem and keep the action barreling forward. The worst such instance is the business with the kicks; towards the end of the half-hour-long, synchronized 4-way kick sequence, we find Cobb and Saito still down in Limbo. We know that this is a tenuous situation because Nolan has gone out of his way to warn us, over and over, about how people can get stuck “down there.” And yet, how do Cobb and Saito come out of it? It’s not shown, but we can infer that they simply shoot themselves (the last image in Limbo we see is old-Saito reaching for a gun).  And then, we realize, come to think of it, that’s how Cobb and Mal escaped Limbo earlier, too, isn’t it? They were down there for “something like 50 years,” fearful that if they ever escaped it would be without their minds intact, and yet all it took was laying on some train tracks to wake them up.

And then, we realize, come to think of it, that’s how Cobb and Mal escaped Limbo earlier, too, isn’t it? They were down there for “something like 50 years,” fearful that if they ever escaped it would be without their minds intact, and yet all it took was laying on some train tracks to wake them up.

So while the other characters all had to jump through hoops (and, literally, perform acrobatics) to pop themselves one level at a time from limbo to the snow fortress to the hotel to the van and finally back to reality aboard the plane, Cobb and Saito are able to just skip all of that shit and wake up directly from limbo. This is convenient, because Nolan doesn’t want to lose his momentum; at this point in the movie what he’s interested in is getting you to his ambiguous ending, where you won’t find a payoff per se, but rather the food for thought that Nolan desperately wants you to emerge from the theater discussing. And again I contend that the reasons why this whole kicking thing, and the details of how Limbo works, don’t really make any sense is because Nolan himself doesn’t really understand them, either. He’s just throwing some trippy shit at you, admittedly in the name of keeping his movie exciting, but he doesn’t want to put in the effort to actually work it all out.

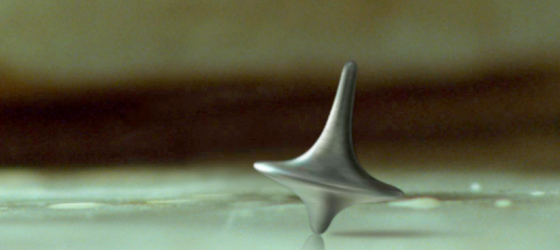

The much-discussed top is what Nolan is driving towards, the reason he glosses over all of these details once Fischer has had his therapeutic moment and the mission of performing Inception has been successful. Because what Nolan has done is exactly what his characters at this point have done: he’s performed Inception on you, the audience, of the same idea that Cobb was able to implant into his wife’s mind. He’s made you doubt “reality”—the reality of the film—and that is the concept he wants to leave you with. Don’t ignore the significance of the fact that Leonardo DiCaprio looks almost exactly like Christopher Nolan in this movie; he’s the director’s representation of himself onscreen, and it’s no coincidence that the director’s primary aim with his film is the same as the main character’s aim in his story.

I think that what’s important about the film’s final image isn’t whether the top stops spinning, it’s the fact that Cobb no longer cares whether it does or not. He’s made his decision, that “this”—wherever “this” may be—is what he wants to know as Reality from now on. Whether he’s still dreaming is irrelevant; this is now his reality. He’s made a decision similar to the one that Joe Pantaliano’s character makes in The Matrix: I don’t really care anymore if this is real or not, I just know that this is what I want to believe as my own reality. The steak tastes too good to decide otherwise; the joy of seeing his children’s faces is too much to write off as not being “real.” (The concept here isn’t as complicated as many have made it out to be; it’s actually explicitly stated earlier in the film—catharsis is catharsis, regardless of whether it occurs in a dream or in one’s waking life.)

As underwritten as I find most of Inception to be, this to me is its biggest redeeming factor. After half-assing a lot of its concepts for most of its duration, in the film’s final minutes Nolan finally solidifies something of a theme, and it’s one that is worthwhile. The idea of subjective reality is one that’s fun and intriguing to explore (Nolan has done so many times before, most notably in Memento), and one that can perpetually be revisited (“Make sure you see it at least twice!”). Coming on the heels of—and tying into—the resolution of Nolan’s other theme, fatherhood, it makes for a finally-satisfying experience.

And yet, there’s still something missing here. The thesis of the film falls a little flat for me, I think due to the fact that it has gone to such lengths to reach this point, and it’s done somewhat of a sloppy job of it in the process. This doesn’t mean that I write the entire thing off, and it certainly doesn’t mean that I think you’re dumb if it does fully work for you. It’s just that it doesn’t quite resonate with me as much as I think it should, and that leaves me with an overall disappointing impression of the film. As I said in my review, Inception is a movie I enjoy—with so much action and mind-bending effects, it’s hard not to have a good time watching it—but I think it could’ve been a movie I really loved.

— —

To give credit where it’s due, most of the links above I found via Jim Emerson’s excellent Scanners blog. Jim’s done a great job collecting, excerpting, and commenting on a lot of the better writings there’ve been related to Inception. While he’s a bit harder on the movie than I am, as he says (and I totally agree), “you don’t have to particularly like a movie in order to find it worthy of analysis and discussion.” And luckily, I do like this movie; it’s the distinction between the reasons why that’s the case and those for why I don’t completely love it that make it so worthy of that analysis and discussion to me in the first place.

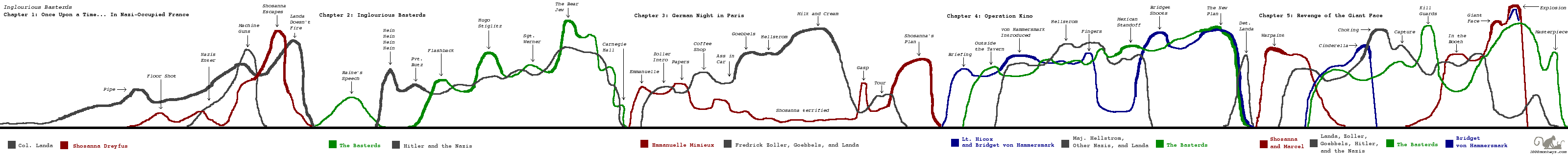

To wrap up my rundown of Inglourious Basterds, the Fugue—maybe I should’ve called it The Well-Tempered Basterd—I wanted to take a step back and try to look at the overall structure as it exists over the course of all 5 chapters of the film. It’s only fitting that I make this a 5-part series, after all.

Quentin Tarantino has always had a reputation of being a great screenwriter, mostly because of his skills with dialogue. He’s also got a reputation as a director who loves to play with his films’ chronologies, particularly with his earlier movies (Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, but also his screenplays for True Romance and Natural Born Killers), though he had his way with the timeline of Kill Bill as well. Inglourious Basterds, to my thinking, represents a new achievement for him in story structure, seeing him effortlessly balance several characters, all of equal importance to his narrative, while playing them off of each other in virtually every combination, the four “voices” of the “fugue” that I’ve been describing chief among them.

I should mention that I did this from memory, after seeing the film twice in the theater on its opening weekend, so it wouldn’t surprise me to learn that I’ve got a few events out of their proper order. (I found a draft of the script online to try to check myself against, but it’s different enough from the final film as assembled that it wasn’t much help.)

The character timelines I’ve included with each chapter are representative of how I tend to picture character arcs in my mind when thinking about a screenplay’s structure. It’s worth pointing out that they were normalized so that the peak of each chapter appeared as the maximum “amplitude” of the character or characters, resulting in a fairly interesting pattern when they’re all looked at together, but one that doesn’t quite capture the real progression over the course of the entire film.

For instance, while the Bear Jew‘s emphatic flourish in Chapter 2 is the emotional and structural peak of that movement, it’s certainly not nearly as large a moment as when the cinema burns and explodes in Chapter 5, as the graph above appears to be indicating. A more accurate overall representation would look more like this:

Now it really looks like a fugue. (I think so, at least…)

I’m hoping to do some more of this type of in-depth analysis in the future, though future such endeavors will probably be without the use of an overextended metaphor—but you never know.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Epilogue

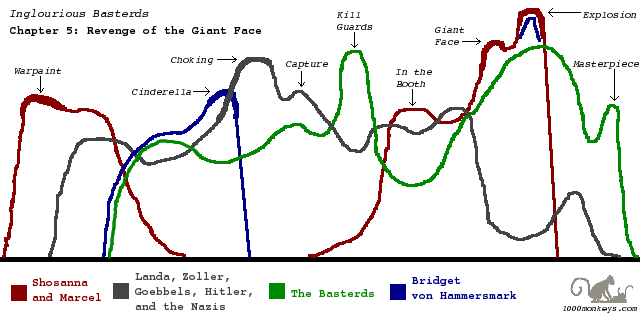

Previously, we’ve looked at the first four chapters of Inglourious Basterds in the context of viewing it as a quadruple fugue. Now we come to the final chapter, where all four voices are present, and each achieves its resolution in what corresponds to Act III. Refer to the intro to “The Inglourious Fugue” for definitions of the terms I’m using and of the primary voices being examined.

Chapter 5: Revenge of the Giant Face

It’s the night of the premiere of Nation’s Pride, Goebbels‘s newest propaganda film, starring its subject, Fredrick Zoller. In the preceding two chapters, we learned of two separate plots to kill the Nazis who have assembled at the cinema: Shosanna and Marcel intend to burn it down with all of the Nazis inside, while Bridget von Hammersmark and the Basterds intend to blow it up.

Chapter 5 opens with Shosanna getting ready for the big night in a scene where Tarantino allows himself to indulge several of his favorite fetishes. As the beautiful French blond applies her makeup as if it were warpaint, re-establishing her voice in this chapter, “Putting Out Fire” blares over the soundtrack. (Not only does Tarantino use a song that was written 40 years after when his film takes place, but he uses the theme from a different movie, too. Pure balls… and it works.) Wearing her red dress, Shosanna dons a black veil and goes to survey her cinema, which the Nazis have liberally decorated. The red and black of her outfit makes her fit right in with their tapestries and posters that litter her lobby, and it also solidifies her as an extension of her cinema. She’s a captain prepared to go down with her ship.

Looking down over the cinema‘s lobby from the 2nd-floor balcony, Shosanna sees the arrival of most of the Third Reich high command: Goebbels, Goring, Boorman (with Hitler on his way). Then the Basterds, loosely disguised as Italian filmmakers, and Bridget von Hammersmark, her foot in a high-heeled cast, make their entrance. This is the first time in the piece when all four primary voices are present simultaneously, and the tension hangs thick in the air.

Col. Landa spots the scheming members of Operation Kino and approaches them in the lobby, once again asserting his voice above the din. After a comedic high point involving contrasting skills with the Italian language, two of the Basterds take their seats in the theater, elevating the dissonance of their voice in this chapter by moving their plan one more step forward. Landa takes von Hammersmark into the office, where we get another tense sit-down scene.  This one doesn’t last very long, though; as soon as the Cinderella moment—QT has a major foot fetish—confirms Landa‘s suspicions (justifying his belief in his own detective skills), he pounces on von Hammersmark with a motion that calls back to his strudel-stabbing in Chapter 3, silencing her voice for good and giving us our most intense look at just what Landa is capable of. This is the first time we’ve seen him involved in an act of violence since Chapter 1, and the first (and only) time it’s been Landa himself who did the killing.

This one doesn’t last very long, though; as soon as the Cinderella moment—QT has a major foot fetish—confirms Landa‘s suspicions (justifying his belief in his own detective skills), he pounces on von Hammersmark with a motion that calls back to his strudel-stabbing in Chapter 3, silencing her voice for good and giving us our most intense look at just what Landa is capable of. This is the first time we’ve seen him involved in an act of violence since Chapter 1, and the first (and only) time it’s been Landa himself who did the killing.

Riding an adrenaline high, the voice of his subject peaking, Landa orders his men to apprehend Lt. Raine, who is taken, along with Pfc. Utivich, to a tavern where the Germans have set up a base of communications.  Here the voice of Landa shifts its pitch, revealing that he is willing to allow the Basterds to go through with their plan, so long as he’s remembered by history as the hero behind it all. This is a different tone than the one we’ve become used to hearing from Landa, as exemplified by his contrasting attitudes towards his nickname (“The Jew Hunter“) between Chapter 1 and now. It’s also another instance of Landa demonstrating his prowess as a detective, a sub-theme of his subject that has surfaced a few times now, but never more forcibly than here. Revealing himself to not be as committed to the Nazi doctrine as he might’ve previously appeared, Landa sides with the cause of the Basterds to “end the war tonight,” and we see a brief flashback disclosing the fact that he planted Raine‘s bomb in the opera box where Hitler and Goebbels are seated.

Here the voice of Landa shifts its pitch, revealing that he is willing to allow the Basterds to go through with their plan, so long as he’s remembered by history as the hero behind it all. This is a different tone than the one we’ve become used to hearing from Landa, as exemplified by his contrasting attitudes towards his nickname (“The Jew Hunter“) between Chapter 1 and now. It’s also another instance of Landa demonstrating his prowess as a detective, a sub-theme of his subject that has surfaced a few times now, but never more forcibly than here. Revealing himself to not be as committed to the Nazi doctrine as he might’ve previously appeared, Landa sides with the cause of the Basterds to “end the war tonight,” and we see a brief flashback disclosing the fact that he planted Raine‘s bomb in the opera box where Hitler and Goebbels are seated.

From here it’s a frantic race to the climax. Back at the cinema, Sgt. Donowitz and Pfc. Ulmer spring into action. While they’re preparing their assault on the Hitler/Goebbels opera box, Zoller excuses himself to make another attempt at winning Shosanna‘s affections. He finds her alone in the projection booth, Marcel having already left to lock the doors to the theater and take his place behind the screen. In the booth, Shosanna and Zoller both meet their end in true spaghetti Western tragic fashion, but not before Shosanna has had a chance to switch to her “special” fourth reel.

Immediately after her death, Shosanna‘s voice reaches its apex, as she appears as a giant face on the screen, tormenting the theater full of Nazis with the information that they are all about to die. Marcel‘s voice gets its last flourish as he flicks his cigarette onto the stack of nitrate films, igniting the screen, with the rest of the cinema to follow. At the same time, the Basterds burst into the opera box and proceed to machine-gun the ever-loving shit out of Hitler and Goebbels, before turning their fire onto the crowd below, mirroring the actions of Zoller in Nation’s Pride shown only moments before. They also take the time to riddle the corpses of Hitler and Goebbels on the ground with more bullets, achieving a bookend effect with the slaughter of Shosanna‘s family under the floorboards in Chapter 1.

Amidst the chaos, the face of Shosanna is still visible in the smoke and flames that have taken the place of the screen, cackling as the theater full of Nazis scramble for their lives. The bombs of Operation Kino then go off, as the Kino voice peaks along with Shosanna‘s in victory. The cinema explodes, blowing the marquee off of the front, Shosanna‘s chorus giving its ultimate flourish.

The coda of Inglourious Basterds takes place in a forest at the Allied lines, where Landa will surrender to Raine and Utivich. Before allowing him to do so, though, Lt. Raine reprises his swastika-carving sub-theme from Chapter 2, as the voice of the film’s titular characters makes its final statement, and Landa‘s is finally silenced.

Previously we looked at Chapters 1 and 2 of “The Inglourious Fugue.” In this post, we’ll look at Chapters 3 and 4, which loosely correspond to Act II in the traditional screenwriting structure. Refer to my intro for a definition of the terms being used here and an outline of how we’re looking at Inglourious Basterds as a fugue.

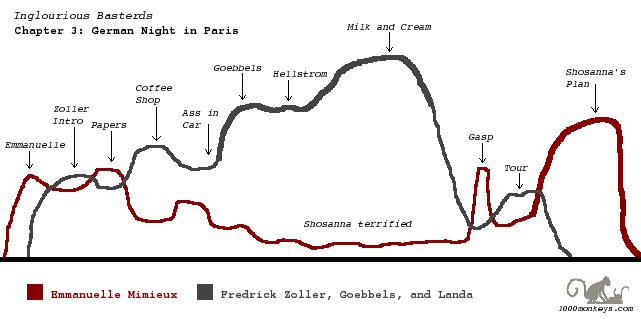

Chapter 3: German Night in Paris

After a great crane shot of the cinema to open the chapter—a trademark Tarantino fetishization—the voice of Shosanna is re-introduced, now in the key of Emmanuelle Mimieux. (QT’s title card tells us that this is four years after the events in Chapter 1, although the dates given—1941 and June of 1944—don’t quite add up.) The cinema serves as Shosanna/Emmanuelle‘s chorus, and we also get a brief introduction to Marcel, her answer. While working on the marquee, Emmanuelle meets Fredrick Zoller, the first voice of the Nazis in this chapter.

After a great crane shot of the cinema to open the chapter—a trademark Tarantino fetishization—the voice of Shosanna is re-introduced, now in the key of Emmanuelle Mimieux. (QT’s title card tells us that this is four years after the events in Chapter 1, although the dates given—1941 and June of 1944—don’t quite add up.) The cinema serves as Shosanna/Emmanuelle‘s chorus, and we also get a brief introduction to Marcel, her answer. While working on the marquee, Emmanuelle meets Fredrick Zoller, the first voice of the Nazis in this chapter.

The next day, In the coffee shop, Shosanna again encounters Zoller, and this time his voice overtakes hers and becomes dominant as he expands his subject, showing its full nature (namely, that he is a German war hero, and the star of a new propaganda film about his exploits).

The next day, In the coffee shop, Shosanna again encounters Zoller, and this time his voice overtakes hers and becomes dominant as he expands his subject, showing its full nature (namely, that he is a German war hero, and the star of a new propaganda film about his exploits).

There is another interlude at the cinema, and then Shosanna is taken by some Nazis to a restaurant, where she meets Joseph Goebbels, whose voice is immediately and strongly established with a small racist monologue about American Olympic gold being earned with Negro sweat.  Goebbels and Zoller then play off of each other, their two voices harmonizing as they discuss the premiere, while Shosanna is drowned out. Major Hellstrom also makes an appearance here, briefly foreshadowing his voice, which will become a foreground subject for a time in Chapter 4.

Goebbels and Zoller then play off of each other, their two voices harmonizing as they discuss the premiere, while Shosanna is drowned out. Major Hellstrom also makes an appearance here, briefly foreshadowing his voice, which will become a foreground subject for a time in Chapter 4.

Chapter 3’s Nazi subject peaks when Landa enters and reasserts his voice by ordering a glass of milk for Shosanna, and again when he makes a big show of ordering cream for their strudel, both callbacks to Chapter 1.  (I love how he attacks his strudel with his fork; it’s a very brief moment, but very effective at foreshadowing the kind of violence he’s personally capable of, which we’ll get to witness first-hand in Chapter 5.) Landa also recapitulates Goebbels‘ racism sub-theme, remarking that being a projectionist would be a good job for “them” (Negroes). This scene is full of tension, with Landa‘s sly smirk and pleasant facade undermining his true nature, which we were witness to in Chapter 1, and contrasting with Shosanna‘s inner struggle to remain calm, which her face almost betrays—Mélanie Laurent is unbelievable in this scene.

(I love how he attacks his strudel with his fork; it’s a very brief moment, but very effective at foreshadowing the kind of violence he’s personally capable of, which we’ll get to witness first-hand in Chapter 5.) Landa also recapitulates Goebbels‘ racism sub-theme, remarking that being a projectionist would be a good job for “them” (Negroes). This scene is full of tension, with Landa‘s sly smirk and pleasant facade undermining his true nature, which we were witness to in Chapter 1, and contrasting with Shosanna‘s inner struggle to remain calm, which her face almost betrays—Mélanie Laurent is unbelievable in this scene.

When Landa finally exits, Shosanna is at last allowed to let out a gasp, releasing the tension that had been established. We then jump to later that night, as Goebbels, Zoller, and a few other Nazis come to check out the cinema. While they’re attending a screening, Shosanna reveals to Marcel her plan to burn it down while the premiere is taking place, setting in motion the first of two assassination plots that will be undertaken in Chapter 5.

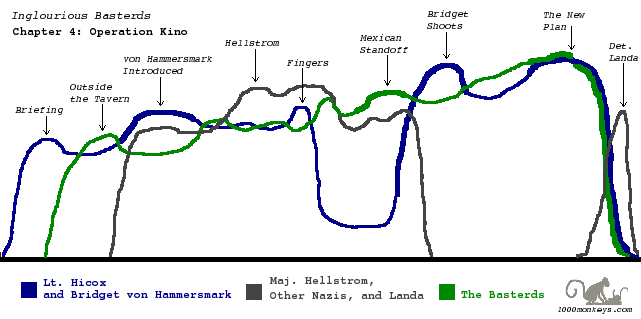

Chapter 4: Operation Kino

Finally, the fourth and final primary voice is introduced, as Lt. Archie Hicox is recruited by General Ed Fenech to take part in Operation Kino. Outside of the small tavern in the village of Nadine, the Basterds re-state themselves, and begin to harmonize with the voice of Operation Kino as Hicox joins their ranks.

Finally, the fourth and final primary voice is introduced, as Lt. Archie Hicox is recruited by General Ed Fenech to take part in Operation Kino. Outside of the small tavern in the village of Nadine, the Basterds re-state themselves, and begin to harmonize with the voice of Operation Kino as Hicox joins their ranks.

In the basement tavern, we meet Bridget von Hammersmark, who is fraternizing with some Nazis, her countersubject. The Kino–Basterds enter and von Hammersmark joins them. After some more banter, Major Dieter Hellstrom makes his presence known, asserting his voice against the Basterds‘ and von Hammersmark‘s. There is another scene of beneath-the-surface rising tension, much like the one between Landa and Shosanna in Chapter 3, as well as another recapitulation of the racism Nazi sub-theme when Hellstrom conflates “American Negroes” with King Kong. This time, the tension boils over when Hicox gives himself away by holding up the wrong three fingers.

In the basement tavern, we meet Bridget von Hammersmark, who is fraternizing with some Nazis, her countersubject. The Kino–Basterds enter and von Hammersmark joins them. After some more banter, Major Dieter Hellstrom makes his presence known, asserting his voice against the Basterds‘ and von Hammersmark‘s. There is another scene of beneath-the-surface rising tension, much like the one between Landa and Shosanna in Chapter 3, as well as another recapitulation of the racism Nazi sub-theme when Hellstrom conflates “American Negroes” with King Kong. This time, the tension boils over when Hicox gives himself away by holding up the wrong three fingers.

A shoot-out ensues between the Nazis, the Basterds, and Hicox, appearing to leave only Master Sgt. Wilhelm (the new father) alive. Lt. Raine‘s voice enters from the street above, establishing Tarantino’s requisite Mexican standoff (the only one, to my recollection, that is explicitly referred to as such in the film), which is brought to an abrupt resolution when von Hammersmark‘s voice re-asserts itself by shooting Wilhelm.

A shoot-out ensues between the Nazis, the Basterds, and Hicox, appearing to leave only Master Sgt. Wilhelm (the new father) alive. Lt. Raine‘s voice enters from the street above, establishing Tarantino’s requisite Mexican standoff (the only one, to my recollection, that is explicitly referred to as such in the film), which is brought to an abrupt resolution when von Hammersmark‘s voice re-asserts itself by shooting Wilhelm.

The end of Chapter 4 mirrors the end of Chapter 3, with a scene at the veterinarian’s office, where von Hammersmark‘s bullet wound is to be treated, during which the Basterds, along with von Hammersmark, hatch a plan of their own to blow up the cinema on the night of the premiere, as it’s revealed to us that Hitler will be in attendance. Landa‘s voice re-enters briefly in the tavern, where he retrieves the napkin that von Hammersmark had autographed, calling back to his assertion in Chapter 1 that he was a skilled detective.

Now the wheels are in motion for a climactic collision of the two separate assassination plots, and the stage is set for Chapter 5, which we’ll get to next.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Chapters 3+4

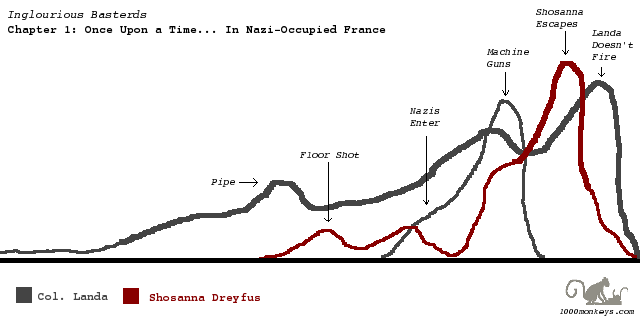

Refer to my “Inglourious Fugue” intro for an explanation of what’s going on in this post. Here we’ll turn to an analysis of the first two chapters of Inglourious Basterds, viewing its construction as a fugue.

Roughly speaking, Chapters 1 and 2 correspond to the traditional Act I, providing the setup for the film.

Chapter 1: Once Upon a Time… In Nazi-Occupied France

The film opens with an exposition, introducing the voice of Perrier LaPadite, which will quickly be drowned out by that of Col. Hans Landa of the SS. Landa gets ample time to establish himself as the primary voice of the piece, introducing several themes that will be revisited throughout.

The first chapter is a slow build, establishing the tone of the film as a spaghetti Western that happens to take place during WWII (Chapter 1 is an homage to The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly). Landa‘s voice gradually establishes itself at the house of LaPadite, making its first flourish when he pulls out his giant pipe in a peacock-like display of masculinity. As Landa and LaPadite converse, the camera slowly drops down beneath the floorboards to show us the Dreyfus family hiding underneath, introducing the first (and primary) countersubject to Landa. There’s also a minor answer to Landa that pops up here, when he asks for a glass of milk.

Tarantino’s camera spins around the table as the Landa voice flits about with his monologue about the Germans (hawks) and the Jews (rats), creating dissonance within the subject. The Nazis enter the house, establishing themselves as an answer to Landa‘s subject, and we catch another glimpse of the Dreyfus’ eyes through the floorboards, which counterpoint the Nazis’ sub-voice as well.

The Nazis’ voice peaks when they machine-gun the floor, killing all of the Dreyfuses except for Shosanna. As Shosanna escapes, her voice in the first chapter peaks. Landa‘s own subject rises as she runs across the field, fading out quickly after he chooses not to fire his Luger into her back, having fully established itself.

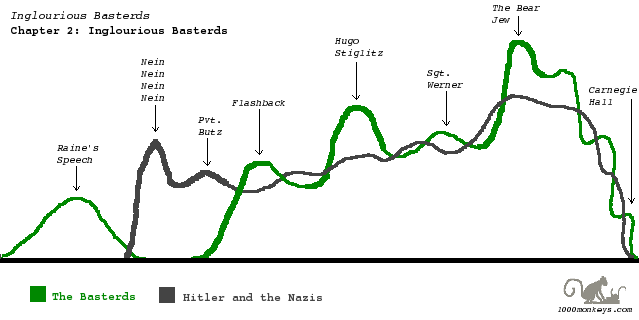

Chapter 2: Inglourious Basterds

In Chapter 2, a new voice is introduced, with Lt. Aldo Raine giving his recruiting speech to the rest of the Basterds. This is abruptly met with a countersubject when we cut to Hitler screaming, “Nein! Nein! Nein! Nein! Nein!”  Here Hitler is serving as the same element as Landa did in the first chapter, as if to restate the same theme, this time in a different key. He interrogates Pvt. Butz, a sub-voice, on his encounter with the Basterds, and as Butz relates his tale in flashback, the two subjects of Chapter 2 play against each other.

Here Hitler is serving as the same element as Landa did in the first chapter, as if to restate the same theme, this time in a different key. He interrogates Pvt. Butz, a sub-voice, on his encounter with the Basterds, and as Butz relates his tale in flashback, the two subjects of Chapter 2 play against each other.

Tarantino cuts between Butz telling the story to Hitler and the images of the Basterds carrying out the deeds he’s describing. The Basterds‘ voice flourishes with the story of Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz as a flashback-within-a-flashback, which QT handles effortlessly (as he also did in Kill Bill Vol. 2).

We then get another answer to the Nazi/Hitler subject in the form of Sgt. Werner, who is quickly overshadowed by the voice of Lt. Raine.  The peak of Chapter 2 for the Basterds comes when we’re introduced to Sgt. Donny Donowitz (“The Bear Jew“), who is commanded by Raine to oblige Werner‘s desire to die for his country, which he happily (and brutally) does.

The peak of Chapter 2 for the Basterds comes when we’re introduced to Sgt. Donny Donowitz (“The Bear Jew“), who is commanded by Raine to oblige Werner‘s desire to die for his country, which he happily (and brutally) does.

For the rest of the scene, QT again cuts back and forth between Butz telling his (abridged) story to Hitler and Raine completing the Basterds‘ subject for this chapter. The swastika-carving answer to the Basterds‘ subject is introduced as Chapter 2 winds down.

At this point, three of the fugue’s four primary elements have been established, and the tone of the overall piece has been set. In the next post, we’ll look at Chapters 3 and 4, where the stakes are increased significantly, and the structure continues to become more complex.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Chapters 1+2

In my review of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, I mentioned that the narrative is constructed like a fugue. As I said, I find this to be a fascinating structure, so I wanted to explore it in depth, both to point out exactly what I meant by it—to clarify the point I was making—and to solidify my interpretation of the screenplay’s assembly.

By their nature, these posts will be rife with spoilers.

There’s a pretty detailed Wikipedia article on fugues, and there’s a better overview on this page, but they’re more technical than I’m going to get. (While there was a point in my life that I had a pretty sophisticated formal music education, it’s been almost a decade now since I’ve studied music academically, and I’m not going to pretend to remember the intricacies or formalities of musical analysis. Besides, that’d make for much more boring posts.) What I am going to do, though, is to speak of the characters in Inglourious Basterds as if they were musical voices, and (hopefully!) show how they enter, exit, intermingle, and eventually come together much in the style of a quadruple fugue. I’m focusing on structure here, and won’t endeavor to belabor my metaphor even further by trying to fit the various appearances of the characters into any more of the formally-defined fugal actions beyond the structural and superficial ones.

The language of musical theory has a lot of variations, so to try to keep things from getting too confusing and complicated, here are the main terms I’m going to use and how I’ll use them:

- A subject is a primary melody, sometimes also called a voice or an element. It’s introduced and then re-visited throughout the piece, often in different keys, typically becoming dissonant at one point before eventually being resolved in its initial key.

- An answer or counterpoint is like a sub-subject. It’s another way of stating the same musical idea, usually in a different key, or shifted on the scale. It’s not as fully-developed as the subject, but its presence helps to enhance the subject.

- A countersubject is a voice that contrasts with the subject, generally by conveying an opposing style or idea. Sometimes a melody (character) will appear as the countersubject in one movement (chapter), but as the primary subject in another.

Because I find the terms counterpoint and countersubject to be confusing (they have almost completely opposite meanings, despite their syntactical similarities), I’ll prefer to use answer or sub-voice to describe a thematic element (character) that reinforces a subject, avoiding counterpoint altogether.

The four voices in Inglourious Basterds, as I see them, are:

Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz): Introduced at the start of the film in Chapter 1, Landa is the primary and most constant subject throughout the story. His sub-voices are Goebbels, Hitler, and the rest of the Nazis that appear throughout the film. He appears prominently in Chapter 1; he’s re-introduced in Chapter 3; one of his sub-voices is especially present in Chapter 4, the end of which sees him taking its place; he’s present throughout Chapter 5, along with all of his sub-voices, and finds his resolution when he captures Lt. Raine; his voice is found echoing until the very end, in the forest coda.

Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz): Introduced at the start of the film in Chapter 1, Landa is the primary and most constant subject throughout the story. His sub-voices are Goebbels, Hitler, and the rest of the Nazis that appear throughout the film. He appears prominently in Chapter 1; he’s re-introduced in Chapter 3; one of his sub-voices is especially present in Chapter 4, the end of which sees him taking its place; he’s present throughout Chapter 5, along with all of his sub-voices, and finds his resolution when he captures Lt. Raine; his voice is found echoing until the very end, in the forest coda. Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent): Introduced at the end of Chapter 1 as a countersubject to Landa, Shosanna is re-introduced in a different key as Emmanuelle Mimieux in Chapter 3, where her sub-voice is Marcel (Jacky Ido), and her countersubject is Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl). She’s re-introduced again in Chapter 5, where her voice reverts back to its original key after she’s been shot, as her face—as Shosanna again—appears on the screen (and in the smoke).

Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent): Introduced at the end of Chapter 1 as a countersubject to Landa, Shosanna is re-introduced in a different key as Emmanuelle Mimieux in Chapter 3, where her sub-voice is Marcel (Jacky Ido), and her countersubject is Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl). She’s re-introduced again in Chapter 5, where her voice reverts back to its original key after she’s been shot, as her face—as Shosanna again—appears on the screen (and in the smoke). The Basterds: Introduced in Chapter 2, with Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt) as the primary subject. The sub-voices are the rest of the Basterds, specifically Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz (Til Schweiger), Sgt. Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth), and Pfc. Smithson Utivich (B.J. Novak). There’s also a thematic answer in Raine’s habit of carving swastikas into the foreheads of the Nazis he allows to survive. The Basterds are re-introduced in Chapter 4, where their countersubjects are the Nazis in the tavern and Landa. Their voice is resolved in Chapter 5, with an echo of their sub-voice serving as the film’s coda.

The Basterds: Introduced in Chapter 2, with Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt) as the primary subject. The sub-voices are the rest of the Basterds, specifically Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz (Til Schweiger), Sgt. Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth), and Pfc. Smithson Utivich (B.J. Novak). There’s also a thematic answer in Raine’s habit of carving swastikas into the foreheads of the Nazis he allows to survive. The Basterds are re-introduced in Chapter 4, where their countersubjects are the Nazis in the tavern and Landa. Their voice is resolved in Chapter 5, with an echo of their sub-voice serving as the film’s coda. Operation Kino: This subject is introduced in Chapter 4 via Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender), when he’s briefed by General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers), and is then re-introduced as Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger) in the tavern scene, where the Nazis (and later Landa) are the countersubject. The Kino voice becomes intertwined with those of the Basterds and Shosanna in Chapter 5, and all three reach their resolution simultaneously during the film’s climactic scene.

Operation Kino: This subject is introduced in Chapter 4 via Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender), when he’s briefed by General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers), and is then re-introduced as Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger) in the tavern scene, where the Nazis (and later Landa) are the countersubject. The Kino voice becomes intertwined with those of the Basterds and Shosanna in Chapter 5, and all three reach their resolution simultaneously during the film’s climactic scene.

I’m using colors to try to help distinguish the various voices and sub-voices, so I apologize to anybody who might be color-blind. I’m sure there’s a more accessible way of doing this that I’m not aware of.

So hopefully now the stage is set. I’m splitting this up into multiple parts, like Todd Alcott does, in the hopes of aiding in readability. In the next post we’ll take a look at the first two chapters of Inglourious Basterds, with all of this in mind.

Comments Off on The Inglourious Fugue: Intro