To wrap up my rundown of Inglourious Basterds, the Fugue—maybe I should’ve called it The Well-Tempered Basterd—I wanted to take a step back and try to look at the overall structure as it exists over the course of all 5 chapters of the film. It’s only fitting that I make this a 5-part series, after all.

Quentin Tarantino has always had a reputation of being a great screenwriter, mostly because of his skills with dialogue. He’s also got a reputation as a director who loves to play with his films’ chronologies, particularly with his earlier movies (Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, but also his screenplays for True Romance and Natural Born Killers), though he had his way with the timeline of Kill Bill as well. Inglourious Basterds, to my thinking, represents a new achievement for him in story structure, seeing him effortlessly balance several characters, all of equal importance to his narrative, while playing them off of each other in virtually every combination, the four “voices” of the “fugue” that I’ve been describing chief among them.

I should mention that I did this from memory, after seeing the film twice in the theater on its opening weekend, so it wouldn’t surprise me to learn that I’ve got a few events out of their proper order. (I found a draft of the script online to try to check myself against, but it’s different enough from the final film as assembled that it wasn’t much help.)

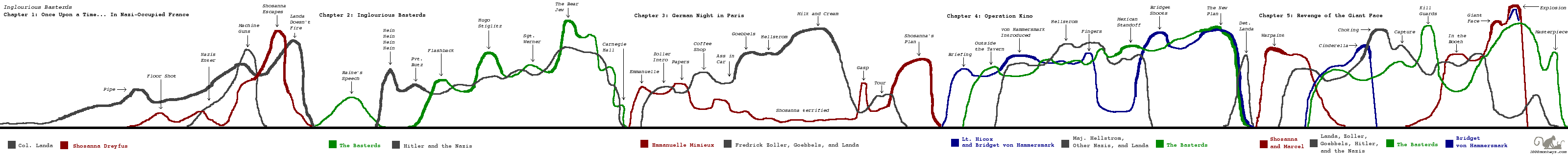

The character timelines I’ve included with each chapter are representative of how I tend to picture character arcs in my mind when thinking about a screenplay’s structure. It’s worth pointing out that they were normalized so that the peak of each chapter appeared as the maximum “amplitude” of the character or characters, resulting in a fairly interesting pattern when they’re all looked at together, but one that doesn’t quite capture the real progression over the course of the entire film.

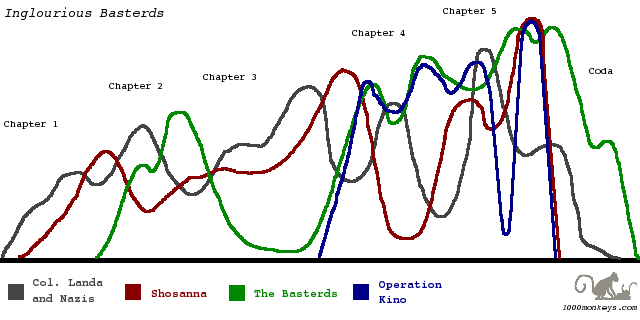

For instance, while the Bear Jew‘s emphatic flourish in Chapter 2 is the emotional and structural peak of that movement, it’s certainly not nearly as large a moment as when the cinema burns and explodes in Chapter 5, as the graph above appears to be indicating. A more accurate overall representation would look more like this:

Now it really looks like a fugue. (I think so, at least…)

I’m hoping to do some more of this type of in-depth analysis in the future, though future such endeavors will probably be without the use of an overextended metaphor—but you never know.